Sheriff Showdown

Bitter Debate Over New Jail, Immigration, and Leadership Dominate Sherriff's Race

Candidates running for elected office need a thick hide to survive the campaign trail. Santa Barbara Sheriff Jim Anderson, now facing off against Lompoc Police Chief Bill Brown for a second term, seems not to have such a protective covering. “I’m disgusted with the whole thing,” Anderson exclaimed recently. “I get mad just thinking about it.”

It shows. After a candidates’ forum two weeks ago, Andersona Lompoc resident for the past 40 yearsrefused to shake hands with his challenger, Brown, the police chief of his hometown.

At forums, Anderson questions whether a small town chief such as Brown has the experience to operate the Sheriff’s Department, with its 700 employees, 1,100 jail inmates, and $86 million budget. And he increasingly attacks Brown’s basic integrity and honesty. Brownpoised, articulate, and far more comfortable in public than his opponentcharges that under Anderson, department morale has tanked, relations with other agencies have soured, and the sheriff himself has become the object of public ridicule. Is this just another story about a rough battle between two candidates?

Perhaps, but in private Anderson tells a different tale. He talks almost exclusively about Jim Thomas, Santa Barbara’s politically powerful former sheriff who opposed Anderson in the June primary but placed third. Anyone listening might easily conclude Anderson is still running against Thomas rather than Bill Brown.

He blames Thomas for the embarrassing meltdown of the Sheriff’s Council, a celebrity-studded group that has raised big bucks for the department. He holds Thomas responsible for securing endorsements for Chief Bill Brown from District Attorney Tom Sneddon, former probation chief Sue Gionfrido, the Deputy District Attorneys Association, and the probation officers union. Not surprisingly, Brown and the other players scoff at being anybody’s proxies. Prosecuting attorney Alan Kaplan of the Deputy District Attorneys Association said, “Pure and simple, our endorsement of Bill Brown is a vote of no confidence in Jim Anderson.”

Anderson is fighting back with impressive endorsements of his own: The Santa Barbara Police Officers Association and four of the five county supervisors are the most recent. Conventional wisdom holds that, as the incumbent, Anderson has the edge. But conventional wisdom utterly failed to anticipate Brown’s surprising come-from-behind second-place showing in the primary. Brown has consistently defied efforts to pigeonhole him as a Podunk police chief. Last year, for example, Brown served as president of the California Police Chiefs Association. In Santa Barbara’s law-and-order circles, Brown impressed many with his smarts. While on the board of the chiefs association, Gionfrido said Brown routinely called her with ideas on how the probation department might weather state budget cuts. “I would say there’s a significant difference between active and passive leadership. Jim Anderson worked with us, but at our instigation. Brown called us up with suggestions to help us out,” she said.

Up Through the Ranks

Jim Anderson arrived in Lompoc 40 years ago at age 10. Vandenberg Air Force Base was the last stop for his father, who retired there after a career in the Air Force. His mom operated a beauty salon, and his father worked for the telephone company. One of seven kids, Jim Anderson first developed an interest in law enforcement through the police department’s Explorer program for high school students. He enrolled in Allan Hancock’s Administration of Justice program and eventually snagged an entry level position with the Sheriff’s Department as a crime scene technician.

After putting himself through the academy, Anderson became a sworn officer in 1976 and worked his way steadily through the ranks. People who worked with him back then remember a hard-working, straight-shooting guy with a keen eye for making little improvements that mattered. Anderson said he tried to avoid the bruising internal conflicts that would engulf the department whenever there was a sheriff’s race. “I was loyal to whoever was in charge,” he said. “I think that’s a good policy.”

When John Carpenter was sheriff and an ambitious young lieutenant named Jim Thomas tried to take him down, Anderson was loyal to Carpenter. But when Carpenter retired in 1989 and Thomas beat Carpenter’s hand-picked successor, Anderson was loyal to Thomas. Under Thomas, Anderson was promoted twice, eventually to jail commander.

As sheriff, Thomas proved a charismatic, media-savvy, forceful advocate for public safety. In 1993, Thomas started the Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Council to help raise funds for bullet-proof vests and bomb squad equipment. That it also happened to cultivate broader political support for Thomas was lost on few. Today, Anderson says he began worrying about Thomas throwing his political weight around, especially on behalf of candidates in the intensely polarized 3rd District. When people under Thomas’s command helped stir up a hornet’s nest that resulted in a 2002 recall campaign against Supervisor Gail Marshall, it came as no surprise that Thomas announced he would not seek reelection as sheriff but would run to replace Marshall should the recall succeed. It didn’t.

The first trouble with Thomas, according to Anderson, began when he told the sheriff he was thinking of running against him in the 1998 race. He didn’t expect to beat Thomas, he said, but to develop name recognition. Anderson claims Thomas vowed to “whup him” and then not so subtly threatened him by saying his chances for promotion would be damaged if he decided to run. Thomas has denied this, calling Anderson “a liar.” In any event, Anderson did not run, and he was promoted.

When Anderson finally declared in 2002, he positioned himself as the prototypical anti-politician. Throughout both campaigns his mantra has been, “I’m not a politician, I’m a law enforcement officer.” But for Anderson, that’s been both a blessing and a curse. Supported by the Deputy Sheriff’s Association (DSA) leadership, he secured the county supervisors’ approval for an expensive retirement deal for his deputies. This package-plus a 12 percent pay increase passed shortly before Anderson took over-helped stem the flood of deputies fleeing to better-paying agencies.

Anderson likes to point out that during his watch, crime has been down and arrests have been up. It’s also true that the department has had its most intense media scrutiny ever. There was the raid on pop singer Michael Jackson’s Neverland estate and the excruciating insanity surrounding the trial itself. International fugitive Jesse James Hollywood, wanted for masterminding the brutal slaying of 15-year-old Nicholas Markowitz, was finally arrested. Earlier this year, a former postal worker went berserk, killing eight employees at the Goleta Postal Annex. And finally, deputies managed to round up 400 malnourished mustangs from the ranch of former race-car driver Slick Gardner without deputies being injured or horses killed. With such accomplishments, Anderson can be excused for thinking his reelection campaign would be a walk in the park. And until last autumn, there was little to suggest otherwise.

Then news began circulating that big-game hunter and Sheriff’s Council president James Towle “bitch-slapped” former president Chris Edgecomb in Anderson’s presence. Wags wondered why a sheriff couldn’t keep two rich alpha males from fisticuffs. When no report was filed, critics charged the sheriff with protecting well-heeled donors. When the DA reported that Anderson had pressured Edgecomb not to file charges-at the instigation of Sheriff’s Council potentate Andy Granatelli-detractors claimed he looked weak. When Chumash Casino stickers appeared on Sheriff’s Department Search and Rescue vehicles-in exchange for a $125,000 donation-even disinterested observers worried that the department was compromised. Then Anderson handed out realistic facsimiles of sheriff’s badges to $10,000 donors, and even some commanders thought an ethical line had been crossed.

In December, the accusations got more serious. Council president-elect Helen Jepsen, a close friend of Anderson’s, was accused of cooking the books by four former council presidents. On December 15, as the council was slated to discuss these allegations, Anderson abruptly announced that to protect the department’s integrity he was severing relations with the Sheriff’s Council. Before the stunned assembly, he ordered his deputies to collect the faux badges from the donors. Critics-including his three primary challengers: Thomas, Brown, and Butch Arnoldi-charged that he had put his friendship with Jepsen above the department, cutting off the $2 million it received yearly in council donations. On Christmas Eve, attorneys representing the four past presidents filed a lawsuit demanding a full accounting of the Sheriff’s Council books.

Consistently, Anderson has dismissed the uproar as “a contrived controversy” conjured by Jim Thomas to undermine his reelection; that Thomas participated in two lawsuit planning meetings; that Edgecomb never said he wanted to press charges; that the DA’s report accusing him of pressuring Edgecomb was wrong, and that Edgecomb was a liar for saying he had. As for the Chumash stickers and the sheriff badges, Anderson said these were originally fund-raisers initiated by Thomas. He had expanded on them to compensate for the county’s budget shortfall. (Thomas countered that his badges always looked like gags, and the sticker program never involved departmental vehicles.)

Jepsen’s suit for defamation against Edgecomb and the four past presidents was dismissed on the ground that it was intended to silence a legitimate public debate. Jepsen appealed. In the meantime, everyone is trying to determine who gets stuck with the substantial legal fees. An audit of the Sheriff’s Council books concluded that Helen Jepsen and her predecessors, many aligned with Jim Thomas, were equally guilty of such sloppy bookkeeping practices that it is impossible to determine if all the donations actually made it into the council’s bank accounts.

Today, Anderson is talking about resurrecting the Sheriff’s Council, though he won’t discuss details. Whether Thomas was stirring the pot, as Anderson insists, in a personal vendetta, or whether, as Thomas claims, he acted to stop Anderson from discrediting his beloved department and the organization he had worked hard to form remains open to debate. Thomas has always admitted he first encouraged Brown to run, but began doubting if Brown could overcome his outsider status. He then encouraged a young commander, Dominic Palera, to run. But Palera bowed out, accusing Anderson of threatening his job. “He said, ‘Remember, your job is in jeopardy,'” Palera recalled. “He must have said it a dozen times.” Anderson disputed that. “I told him he needed to think about it,” Anderson said. “Thomas had talked him into it, and I was trying to protect him.”

With Palera out, Thomas decided to jump in himself. Around then, Anderson’s critics within the department went public with their gripes: There was no leadership. Questions involving mundane matters like late-night uniform requirements and proposed schedule changes languished in committees set up by Anderson. Worse yet, the sheriff promoted for personal loyalty rather than competence. Thomas loyalists referred to Anderson’s core group as “the revenge of the nerds.”

Anderson supporters, like Lt. Phil Willis, shot back that the sheriff was trying to promote an internal democracy to which many paramilitary organizations were not accustomed. “Anderson encourages people to make decisions on their own rather than dictating how they should be run. He leads by consensus.”

There is less debate about Anderson’s performance in the District Attorney’s office. “Essentially, we believe that Sheriff Anderson, who was the jail commander, does not have the ability to view the department as a whole,” said Alan Kaplan, spokesperson for the Deputy District Attorney’s Association. “There needs to be an examination to determine why there appears to be a group of people who’ve been promoted as a result of favoritism, as opposed to more solid reasons.” In forums, Anderson has defended his promotion policies and said “DAs want everyone to plea out. Otherwise, it makes their life difficult.”

Getting to Be Chief

As a child, Bill Brown’s family moved around a lot. He reckons he lived in 22 different places by the time he was 14. Brown’s father was a field director for Billy Graham’s religious crusade, and it wasn’t until he took over the Burbank-based film ministry that the family finally settled down. In high school, Brown first thought about working in law enforcement after he took a class taught by an LAPD officer. When he graduated, Brown trained for and got a job as an emergency medical technician (EMT) where he acquired the gritty experience that prepared him for his ultimate goal-a law enforcement career. Since then Brown has worked on a small town force and in an inner city police department, graduated from the FBI academy, and was appointed police chief of a college town in Idaho.

In 1995, Brown took over Lompoc’s small, chronically understaffed department in a city then plagued with drug, gang, and crime problems. Brown’s charge was to initiate community-oriented policing. He threw himself into the task. In short order he impressed the then county probation head Sue Gionfrido. “He took an active interest in alternatives to the traditional tail ’em, nail ’em, and jail ’em law enforcement,” she said. “He schooled himself in other approaches and tried to find out what actually worked.” Sheriff Anderson has dismissed Gionfrido’s endorsement of Brown as a political favor to her personal friend Jim Thomas. “I’ve been a long-time friend of Jim Thomas, “Gionfrido acknowledged, “but I didn’t endorse Thomas in the primary. I endorsed Bill Brown.”

Brown proved to be a master in community outreach. He promoted athletic programs such as youth soccer and boxing; got Lompoc cops their own public access TV show in which officers describe their efforts, highlight the town’s most wanted, and bring on guests. He also started a free car show now hosted annually by the Lompoc police, featuring about 300 hot rods, live music, food booths, and family-friendly activities. This year the event raised $25,000 for Special Olympics. Brown brought the National Night Out event to town, a block party held every August, usually in one of Lompoc’s high crime neighborhoods. In order to reach church groups and neighborhood activists, he divided the city into four sectors and formed committees to advise the department on concerns within each area.

Bill Federmann, a pastor who served on one such committee, positively gushes about Brown. When a string of burglaries hit a neighborhood, Brown and a captain met with residents and almost immediately dispatched a nighttime bike patrol to the area. The problem was soon solved. Brown is proud of obtaining a court-ordered injunction barring gang members from congregating in front of Lompoc’s schools and certain areas of town. He beefed up the department’s anti-gang and narcotics squads. The goodwill Brown built up paid off when he asked community organizations to help wipe out graffiti and other eyesores. Volunteers now paint over tagging as soon as it happens and remove abandoned or disabled vehicles from the streets.

In Brown’s first years, however, experienced police officers left in droves. In a department of 49 sworn offices, 29 left within a three-year period, mostly to Santa Maria where the police are paid substantially more than in Lompoc. And many of the officers already lived in Santa Maria. But Brown also concedes his early relations with the troops were bumpy. “I was not around a lot of the time,” he said. “They expected the chief to be there giving orders. But I was out in the community or up in Sacramento.”

Tensions between Brown and the force came to a head over the union’s annual Christmas party. According to Sgt. Nate Flynt, the union chief, some of the gift exchanges ranged from risque to raunchy. Members of the public attended these functions and Brown worried it might reflect poorly on the department. He asked the union to tone it down. Instead the gifts got even racier. Eventually, according to Flynt, the union said, “Listen, the association would like to invite you, but we’re off duty and if you don’t like it, don’t come.” Brown recognized that tensions extended well beyond disagreements over the Christmas party. “He called a big meeting and said, ‘I’m here. I want to do a good job. Let me have it,'” said Flynt. “Our membership spoke freely. It was very emphatic.” Flynt credits that meeting with a dramatic improvement in relations between Brown and his officers. “He started a very purposeful effort to get to know each of us as people. He meets now once a month with the union for breakfast. We can talk about everything-problems, rumors-anything. It’s really turned around.”

Improved communications and a 10 percent pay hike-approved by the Lompoc City Council two years ago-have gone a long way to stabilizing the department. Brown has also launched an aggressive bottom-up recruiting campaign in Lompoc itself, encouraging high school students to consider a career in law enforcement. In addition, he’s tried to keep experienced officers from straying by offering a wide array of specialty assignments and training to bolster their professional development.

Even though Lompoc spends a whopping 72 percent of its general fund on police and fire protection, that’s not enough, according to an Ad Hoc Safety Committee report last year. With 49 officers, Lompoc has the lowest ratio of police to citizens in the county. The average police caseload increased from 47 per month in 1999 to 99 in 2004. As a result, the report concluded, the clearance rate by Lompoc’s Detective Bureau had dropped from 72 percent in 1998 to 37 percent in 2004. Brown pointed to an unusual spike of crime in 2004 with larcenies jumping from 522 to 810. He said he responded to that by increasing the number of drug-related arrests. “It’s a truism in our business that when you arrest people for drugs, the burglary rate goes down.” And in any case, he added, the serious crime rate dropped 38 percent in the last 10 years and 12 percent last year alone. “We had the lowest number of serious crimes per capita of any city in the county,” he said.

Lompoc city managers have hired a consultant to study putting a sales tax increase on the ballot to finance more public safety. Ron Fink, one of the co-authors of the safety committee report, a Lompoc Planning Commissioner, and a supporter of Sheriff Anderson, faulted Brown for not getting the funding from the City Council. But according to Councilmember Jan Keller, the only member to remain neutral in this race, it’s not that Brown isn’t trying: “My biggest gripe about Chief Brown is that he keeps coming back asking for more.” Keller, who praised Brown as “a real go-getter for grants,” acknowledged his officers were overworked and underpaid. But, she said, the council couldn’t accommodate the chief’s requests without raiding other departments.

Anderson and Fink have seized upon another more recent event to question Brown’s leadership skills. In a nationwide protest in March 2006 against a proposed anti-immigrant bill that would give local law enforcement officials the authority to enforce federal immigration law, many thousands took to the streets throughout Santa Barbara County. Many school kids skipped classes to participate. In Santa Maria, the police led the protestors, and school districts provided buses so the marchers could return to campus as soon as possible. In Lompoc, school officials asked police to stop the student marchers before they got going. According to Jeannie Barrett of the California Rural Legal Assistance, half of Lompoc’s sworn officers participated in an action that culminated with the arrest of 62 middle and high school students. Almost all were Latino. Barrett sued the police department and the school district, citing the provision in the district’s anti-truancy law allowing students to miss classes if they are attending political rallies.

Barrett said Brown immediately acknowledged that his department had screwed up. “I ended up having a lot of respect for him,” Barrett said. “I expected some half-hearted apology. : But he was very forthright and accepted responsibility.” The apology was issued in the Lompoc City Council chambers. Students and their families were present. So was the media. And so, too, was an operative from Anderson’s campaign, Tony Simmons, a one-time sheriff’s reserve deputy and a Lompoc resident. When Brown said he would like to meet with families individually afterward, rather than field questions from the floor, Simmons tried to rally a walkout but got no takers. “It was a little awkward,” said Barrett. “But we were there for the apology, not to make political hay.” Brown stuck around as long as any parents or students wanted to talk to him. “Parents wanted their children to understand they had rights. They also didn’t want their kids to be afraid of the police,” said Barrett. “The whole thing felt real to me.”

At a Goleta forum, Anderson said he favored giving local law enforcement the authority to enforce federal immigration law. He argued, then as now, that it would help his department protect county residents from terrorism. He is worried that Iraqis and Iranians equipped with phony identity cards could slip into the United States from Mexico: “I have no interest in rounding up hard-working people just to send them back to Mexico.” Brown was the first candidate to object to Anderson’s comments and he hasn’t stopped since. He contends Anderson’s position is out of touch with mainstream law enforcement: “When I was with the California police chiefs, we wrote a letter to the attorney general saying we thought it was a terrible idea.” Anderson has countered that Brown is telling Latinos in Santa Maria and Guadalupe that he (Anderson) wants to initiate mass arrests and wholesale deportations. Vic Tognazzini, now running for Congress against Lois Capps and an Anderson supporter, claims he saw Brown directing such a campaign during a recent Mexican Independence Day celebration in Guadalupe. Brown disputes Tognazzini’s claim.

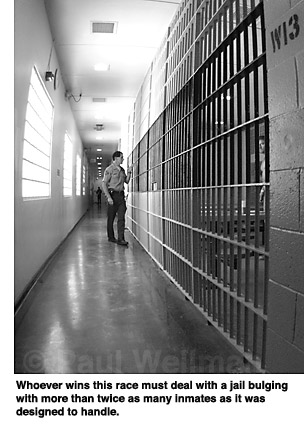

The County Jail Dilemma

The most pressing issue in this race, however, is jail overcrowding. Built 36 years ago, the jail now houses more than twice the number of inmates it was designed to hold. Inmates are sleeping on the floors with little room to separate volatile prisoners from one another.

Anderson’s solution is a new north county jail for 1,500 prisoners. Initially estimated at $153 million, construction costs have soared. Six years ago, a much cheaper plan-to be paid for with a sales tax increase-failed to pass a county vote. Privately, supervisors-even those who’ve endorsed Anderson-have dismissed his plan as impossible. One recently asked, “Where are we going to get the money?”

Anderson’s answer is Sacramento. As chair of the California State Sheriff’s Association committee on new jail facilities, he’s been negotiating with Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and Senate leader Don Perata to place a bond measure on the ballot in a few years. But based on abysmal poll results, state politicians killed a proposed prison bond slated to appear on this November’s ballot. “They have no stomach for that in the Legislature,” Chief Brown charged. “We desperately need a Plan B. The problem is Anderson has no Plan B.”

In the first place, Brown says Santa Barbara County needs to focus on prevention. “Do you know we only have 24 detox beds in this county?” he asked. “That’s astounding.” He also suggests building pre-fab cells as was done in Lompoc’s federal prison. “They have 288 beds, an inmate reception area, a kitchen, a laundry room-the whole thing-for $19 million,” he said. Another proposal is to use Tulare County’s new jail that’s sitting empty because it lacks operational funds. “If we could send the 30 percent of our prisoners who are now serving their sentences-as opposed to the 70 percent awaiting trial-we could achieve some results right now, not sometime way down the road,” Brown said.

Anderson dismissed most of Brown’s suggestions as “short-sighted” and “not cost-effective.” If Santa Barbara were to park its prisoners in Tulare County’s jail, he said, we would have to pay the operating costs, not to mention the cost of transporting prisoners to and fro. “It’s money we should be spending on a more meaningful solution,” he said.

Brown has criticized Anderson’s unilateral decision last August to stop booking people charged with serious misdemeanors into County Jail. He’s not alone. County supervisors, judges, and other law chiefs have complained that Anderson didn’t consult with them prior to issuing his edict. The criticism might increase since the man arrested in the recent shooting of a 60-year-old man on Islay Street had been picked up the week before in Lompoc on an outstanding warrant, but after being sent to the County Jail had been released because of Anderson’s policy.

At a recent forum, Anderson dismissed objections to his unilateral style, saying, “I am the sheriff. I have to make those tough decisions. There was no other way.”

On Election Day, the voters will decide just that.