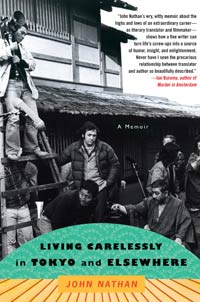

UCSB Professor’s Memoir on Japan, America, Film, and Literature

Crossing Cultures

In a recent conversation, John Nathan, UCSB’s Takashima Professor of Japanese Cultural studies, recalled a trip to Tokyo with his son. “He kept asking, ‘Dad, what has this place got do to with you?'” Nathan said. “That’s a really good and a really troubling question. I didn’t have a great answer, but I could talk about real things: the delicacy, the sensitivity, the beauty of their stories.” That question and its many possible answers lie at the heart of Nathan’s newly released memoir, Living Carelessly in Tokyo and Elsewhere.

An affinity for things Japanese now seems more the rule than the exception among American youth; it wasn’t so during Nathan’s college years in the early 1960s. Relocating early in life from New York to Arizona, he found he needed a way to deal with the rough transition. “I needed something that would distinguish and protect me,” Nathan said. “I thought I would love to have a pet monkey.” He heeded the spirit of his wish, if not the letter, by gravitating toward the Japanese language years later. “It was really like having a pet monkey, because a lot of kids were studying Camus and Western philosophy, and almost nobody was studying Japan.”

The language entered his life humbly. “A Japanese kid who had come to Harvard drew two characters on a napkin for me. In English, it was the unusual word ‘whitlow,’ an infection beneath the nails of the fingers and toes. I thought to myself, ‘My god, these two pictures mean that? I want to learn more about this language.’ I fell in love with it very early on. After four years of school, I was fanatically committed to and submerged in the pursuit of this impossibly difficult language.”

Nathan’s logical next step was to visit Japan itself, where he became the first American to study at the University of Tokyo, immersing himself in the country’s literature. With mastery came the opportunity to translate for such luminaries of 1960s literary Japan as Yukio Mishima and Kenzaburo Åe. “Translation seemed to me to be a halfway house between normalcy and the wild, absurd craziness of artistry. I went out and bought the same Mont Blanc pen the Japanese big shots used, which cost about $200. My total pay for [translating Mishima’s The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea] was $400.”

Nathan later took up filmmaking, first alongside legendary director Hiroshi Teshigahara and then on his own. “I had this idea to take cameras into ordinary Japanese life more deeply than ever before,” he said, “to take American audiences beyond cliche and caricature to the Japanese as real people like ourselves: equally contradictory, equally wise, equally foolish.” The result, a trilogy of documentaries examining a Tokyo caterer, a family farm, and the movie star Shintar’ Katsu, are still screened in film and Japanese studies courses today.

However, after the disappointing performance of Summer Soldiers, his coproduction with Teshigahara, and less-than-encouraging comments about his place in Japan from Katsu and visiting novelist Saul Bellow, Nathan began to think that “the Japan thing had played itself out.” Taking a professorship at Princeton, he spent seven years teaching before resuming his film career in a very different place. “I thought, okay, I’m going to go to California and become a regular filmmaker,” he said. “I’m not going to have anything to do with Japan.”

After penning several television movies, Nathan seized the opportunity to work on the film version of Thomas J. Peters’s In Search of Excellence, leading to a decade spent making commercials and business documentaries, with the intent to prove he didn’t need the exoticism of Japan to excel. Japan nevertheless found its way back to him. “A powerful television producer was making a series of documentaries of the business process. Out of the blue, he called me and asked if I’d make a business film in Japan.” The film, The Colonel Goes to Japan, followed Kentucky Fried Chicken’s hugely successful bid to insinuate itself into Japanese daily life by leveraging what was then considered the American mystique.

After a 15-year hiatus from the academy, Nathan came to UCSB, where he has written books and taught Japanese studies courses ever since. He still meets students with the same intense interest in Japan he had more than 40 years ago. “They’re rare, but they’re certainly there, these kids who are genuinely moved by something they’re feeling about Japanese sensibility, Japanese culture, Japanese achievement,” Nathan said. “I suggest to them that they need to pursue the essence of that by learning more and more so that they get to a place where they can understand what they feel, and so they have reasons for feeling it. I want them to expand the focus of their interest, and I want them to deepen it.” Now, with their professor’s life story in print, they can see exactly how it’s done.