A Million Bucks or Addicts Face Jail Time Instead of Treatment

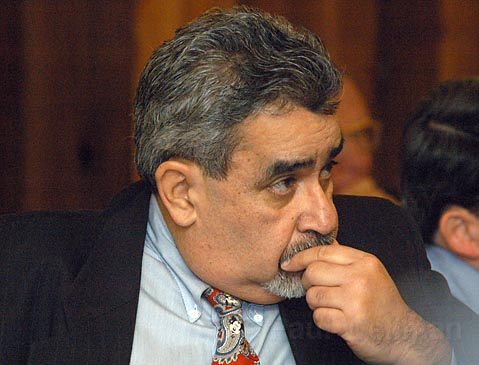

Santa Maria Judge Rogelio Flores warned that the proposed $700,000 cut slated for the county’s Proposition 36 program-designed to keep minor drug offenders out of jail and in treatment instead-would be utterly disastrous. “It’s horrible,” Flores said. “It’s a mess. Everyone’s going to suffer, not just the addicts but the entire community.” Flores said the cuts would prevent the program from helping as many drug offenders as it currently does or keeping them in treatment for as long. “And we’re going to have waiting lists,” he added, “for the first time ever. Can you imagine telling an addict ‘Please wait until a slot opens up?'”

Prop. 36 was approved eight years ago in response to growing frustration by California voters with the cost of incarceration. Providing nonviolent drug and alcohol offenders treatment, the reasoning went, could save money, alleviate prison overcrowding, and help addicts. Funding was guaranteed for the first five years, but after that, the State of California would have to figure out how to pay for the program. Unhappily, this transition period has coincided with the deepening of the state’s budget mess.

Last year, for example, the state cut Santa Barbara’s Prop. 36 funding by nearly $700,000. But the county, enjoying relatively healthy reserves, filled the breach. But this year, the county is looking to cut $25 million from the total budget, meaning that a program used to receiving nearly $2 million a year would need to make do with $1.3 million. And that has Flores fuming. “I’m not smart enough to figure out how to make lemonade out of these lemons,” he said. “What do people in this county want me to do-put these people in jail? Guess what, I’ve got no jail to lock ’em up in. Ours is already full.”

Especially galling to Flores-who regards overseeing the diversion court “the best damn work I’ve ever done”-is that Santa Barbara’s Prop. 36 program has proven successful when compared to other counties. “We’re one of the best in the state. Last year, we saved the county $5 million in incarceration costs,” he said.

Part of the reason Santa Barbara County has succeeded, Flores posited, is that the judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, probation officers, and treatment providers have been working together. But now that there’s less bread on the table, these allies are at risk of becoming adversaries. For example, some grumble that judges and probation officers will not lose funds, only the nonprofit treatment providers. Without this cooperation, Flores said, the addicts will not do as well.

Additionally, the program provides up to 18 months of treatment-longer than many Southern California communities and with focused handholding to keep the clients sober. For struggling clients, Flores said, it’s not unusual for them to see one of the county’s three Prop. 36 judges-himself, Deborah Talmage, and James Iwasko-as many as 30 times. That attention to detail may not be possible with less funding. “Right now, if someone misses a class, I can have a probation officer on him immediately,” said Flores. “That’s what it takes to succeed. With the cuts, who knows when the probation officers will get around to it?”

Flores boasted that the county’s Prop. 36 effort was succeeding despite methamphetamine abuse the likes of which he hasn’t seen during his 21 years on the bench. “It’s like I’m fighting a 200,000-acre forest fire, and they’ve just decided to take away some of my fire engines.”

On June 2, Flores and the other Prop. 36 stakeholders are scheduled to hammer out how best to deal with less. Flores is pessimistic that the county supervisors will rescue the program again, saying the community-based organizations and nonprofits will have to make their case directly to the community. “The Santa Maria Elks raise a million bucks a year auctioning off a pickup truck,” he said. “And that’s about what we need: a million bucks.”