Santa Barbara Printmakers at Channing Peake

17th Annual Juried Exhibition Runs Through September 17

All art records the artist’s impressions of the world, yet only in printmaking does the artist literally press her work into being. Now on view at the Arts Commission’s Channing Peake Gallery are 84 original prints chosen from among more than 250 entries to this year’s Santa Barbara Printmakers juried show.

The selected works represent a range of techniques, from chine collé to drypoint etching, but every one carries the tactile echo of the materials used to produce it—linoleum tiles, woodblocks, Plexiglas sheets—the matrix from which the artist made a lasting impression.

Such echoes make an impact in works like Jim Bess’s “Stargazer,” a painterly monotype that calls to mind Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” In it a shrouded figure gazes from hooded eyes: primitive red features scrawled on an orange face. In confronting this print, the viewer takes on the role of its predecessor—identical and yet mirror-opposite, gazing right back.

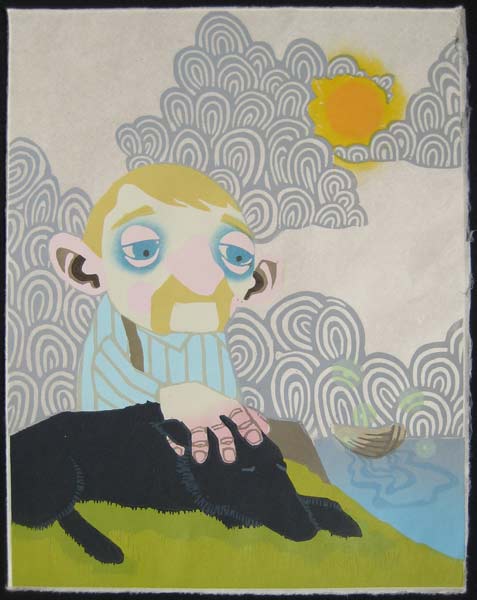

The theme of reflection crops up again in Nicholas Spohrer’s woodcut “Drifting into Time.” Here, an old man sits on a riverbank lost in thought, his thick fingers sinking into his sleeping dog’s fur. Stylized clouds filter the sunshine, and a dinghy drifts downriver, leaving ripples in its wake.

Ripples and whirlpools are also present in Dug Uyesaka’s untitled drypoint etching, where fine lines and dots seem to be spun by an invisible wind. Marie Schoeff’s work in the same medium captures a similar energy, its swirling lines reminiscent of a woman’s hair swept into a loose bun or a pot of noodles caught in a rolling boil.

Some prints tell simple stories: Jason Sober’s polymer plate “Stegosaurus” stands on its hind legs as if asking for a hug. Others are more enigmatic, like Barbara Parmet’s solar etching “Leap,” which captures a woman in midair, her full skirt billowing around her legs and a gauzy headdress soaring behind her as she flies.

Among the more abstract pieces in this show is “Ubi Caritas,” Carolyn Liesy’s mitochondria-shaped mind map—a grayish dappled cloud within which Latin phrases seem to precipitate, ultimately yielding a pile of English words: “Wherever love and compassion are, there god is.”

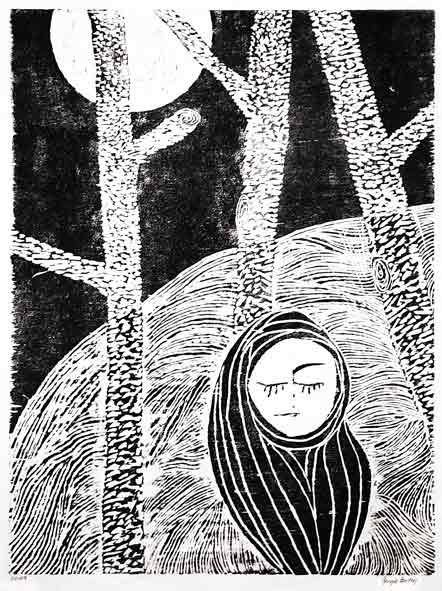

That message finds an echo in Georgia Bertin’s impressive untitled woodcut of a female figure in a forest, while a round, white moon casts its glow over rolling hills and stippled tree trunks. She huddles close to the ground, eyes closed, a dark cloak wrapped around her. It’s an image with archetypal power, one that reminds the viewer of the strength of the human spirit even in the darkest of nights.