One of my big regrets is that I didn’t have Rachel Johansen to open the doors of education for me. My first classroom experience involved well-meaning nuns who put me on notice there was but one path and that those who strayed wound up in Hell. Thankfully for my own children, Rachel — for 31 years one of the pillars of the Starr King Parent-Child Workshop — was all about giving young minds and souls the freedom to wander, choose, to experiment, and to stumble. In Rachel’s world, failure was not failure if you managed to learn something from it, and experience was always the best teacher.

It was Rachel’s mission to create a safe place — for the thousands of kids going through Starr-King during her tenure — to have as many of those experiences as possible. Sometimes that involved protecting the children from their parents’ best intentions.

Then as now, Starr-King requires active parental participation. Parents show up for mandatory Monday night meetings; they also show up to volunteer for playground or inside duty. This involvement is one of the reasons Starr-King has remained so ridiculously affordable. It’s also how parents are supposed to learn. It took me a while to get the picture. I figured parental involvement meant that when my son was painting in the art area, I could join in and paint too. I can’t remember exactly what Rachel said. She could not have been more gentle about it, but she let me know in no uncertain terms that I was intruding not just on my son’s experience, but on the other kids’ as well. Message delivered, with no hard feelings.

At that time, Diane Gonzalez was also a Starr-King parent. She now works at the San Marcos Child Parent workshop doing what Rachel did. In large measure, she’s modeled her approach on Rachel’s. “We’re here to provide an environment where kids are free to do what they want. We’re not here to evaluate it, to judge it, or to even name it from adult perspective,” she explained. “It’s all about what the kids are interested in and seeing where they take it.”

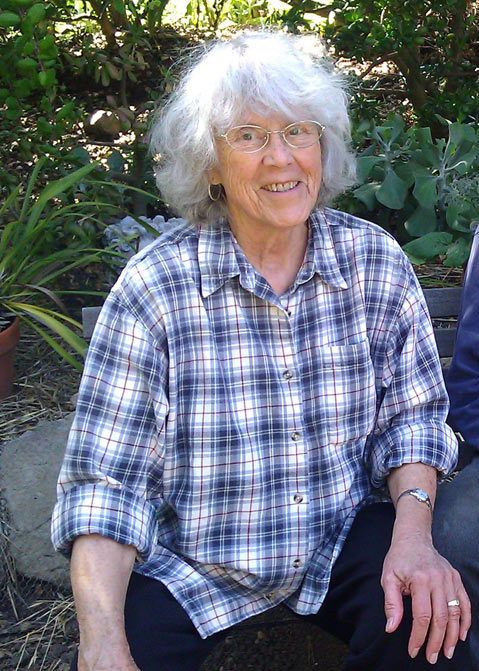

To a blabbermouth like me, Rachel could be unsettling. She didn’t talk a lot. But very often, there was a hint of a smile tugging at her mouth, looking to get born. On the job, Rachel managed to exude a remarkable combination of stillness and warmth. To an uncommon degree, she was who she was and where she was meant to be. I never heard Rachel raise her voice, scold, or seem the least bit frazzled. It was unreal. Except in her case, it wasn’t. Rachel was clearly in charge, and everyone knew it.

As a teacher, Rachel was a shower, not a teller, and her passion was always nature. She was a pioneer in what would later come to be called environmental education, though I’m not so sure she’d approve of the term. Every day she brought a collection of seed pods, grasses, leaves, and wildflowers to class for the kids to do with as they saw fit. She always knew what plants were in bloom and where. Rachel was equally famous for the volume of found objects she brought in, ranging from candy wrappers to dryer lint. Eventually, all these landfill refugees would find their way into some art project.

Part of Rachel’s genius was to tune out the ambient din and simply pay attention to what was in front of her. “Most of us spend so much time distracted,” said Gonzalez. “But Rachel would look at things. I mean really look.” After retiring from Starr King in 1996, Rachel volunteered as a docent at the Natural History Museum. She was quick to get down into Mission Creek and muck about, sharing her enthusiasm for nature — and her extensive knowledge of Chumash paleobiology — with school kids from all over Santa Barbara. Watching Rachel put a plant into the ground was “like going to church,” said her husband, Tony Johansen. Except she was too in love with nature to be pious or preachy about it. Instead, said Kathy Harbaugh, who worked with her at the museum, “With the kids, she was ‘Wow! Isn’t this cool!’”

It was at Starr King that many young souls got their first taste of life outside their family cocoon. Inevitably, heads butted. As referee, Rachel ruled by example, treating everyone with the same respect, regardless of age or emotional maturity. David Alonzo-Maizlish — now 37 years out of Starr King — wrote, “Rachel helped me learn how to listen to others. This simple, profound skill comes to mind when I think of her; how she would listen to me no matter if I was angry, scared, or simply prattling on like any other toddler. Her example has stayed deeply with me since then.”

Born Rachel Oatman in Marshfield, Wisconsin, in February 1931, she grew up in Geneva, Illinois, where her father started a business with a process he devised for extracting moisture from cheese whey so it could be used as animal feed stock. On Rachel’s mother’s side there were newspaper people. Rachel studied political science at Stanford University. It was there that she met Jim Schermerhorn, with whom she moved to Santa Barbara in 1955 and whom she eventually married. Rachel and Schermerhorn, a Santa Barbara News-Press reporter with the gift of gab, had two children together but divorced after seven years.

Rachel started at Starr King as a parent, then in 1965 accepted a job as assistant to director Sarah Foote. When Foote retired, she was replaced by Hanne Sonquist. For 23 years, Rachel and Hanne enjoyed an exceptional run together. Rachel married Tony Johansen, having met him when he was a Starr King dad and divorced father of three, in 1973. The clan moved into digs on Glendessary Lane, and they opened their home to Wednesday-evening jam sessions — now officially known as the Glendessary Jam — for banjo, guitar, and fiddle players of the old-timey persuasion. Though Rachel did not join in the jam, she was an avid singer with the Unitarian choir and the Santa Barbara Choral Society.

Rachel died at home October 26 after a eight-month battle with cancer. “Rachel is fine,” she told her husband of 39 years. “But my body has issues.” Before she died, Rachel was surrounded by her family, serenading her with old favorites such as “Amazing Grace,” “Swing Low,” and “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” Since her death, Tony Johansen said people have sought to console him, saying “Rachel is in a better place.” His response? “When she was here, you felt she was already in a better place, and anyone who came in contact with her was in that better place also.”

There will be a memorial gathering for Rachel Johansen at Fleischmann Auditorium at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History on Saturday, January 21, at 3 p.m. Donations — in lieu of flowers — can be sent to the Santa Barbara City College Foundation/Rachel Johansen to benefit the Starr King Parent-Child Workshop.