Barnaby Conrad practiced the old adage “Write what you know.” He would take everyday incidents and turn them into books, articles, or stories to be swapped over drinks. A consummate storyteller, he led no ordinary life.

Born to a wealthy banking family in San Francisco, he counted grandfathers in high places, such as a Montana cattle baron and U.S. Appeals Court judge. Not everyone on the family tree, he would emphasize, led pristine lives — more fodder for his storytelling repertoire.

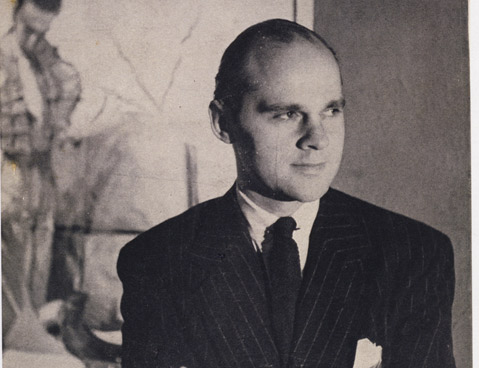

When I first attended the Santa Barbara Writers Conference (SBWC) in June 1978, I knew little about Barny (unusual spelling his choice) Conrad. I read about him in Herb Caen’s column in the San Francisco Chronicle so knew he lived in Santa Barbara, was a writer (almost 30 books), bar owner, and man about the city — any city he was in.

More of the man emerged through Conrad’s stories at weekly writers’ lunches (started by Ross Macdonald in the ’50s) and other occasions. He took a job in the late 1940s as personal assistant to Sinclair Lewis (author of Babbitt). The Nobel Laureate novelist read Conrad’s first manuscript and made one suggestion: “Cut the first 76 pages.” Conrad did, rewrote it, and published The Innocent Villa.

After graduating from Yale in 1943, he took a job as vice consul in Seville, Spain, and indulged in a passion: bullfighting. His friendship with the famous matador Juan Belmonte resulted in Conrad’s second and most popular novel, Matador. At least five books came from those experiences, and he named his popular bar in San Francisco El Matador.

The Conrads’ Rincon beach house reveals even more. His painting studio near the front door, like the house, is crammed with memorabilia and portraits of family members, people’s pets, and famous celebrities. Those of Truman Capote, James Michener, and Alex Haley are missing; they hang in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. He loved trompe l’oeil, and he talked more than once about his favorite, a swimming pool painted on the terrace of a San Francisco penthouse.

During a party once, good jazz piano music caught my attention. At the upright in the hallway, Conrad was playing four-hand piano with famous New York jazz pianist Joey Bushkin. Conrad played by ear. If you hummed a tune, he could make it jazz, waltz, or boogie-woogie. He told about playing “fraternity piano,” as he called it, at his own El Matador. “I was secure in the knowledge that no one could fire me.”

Conrad grew up visiting his grandmother in Montecito. When he and his wife, Mary, moved here in the ’60s, Conrad had a vision of a first-class writers’ conference in Santa Barbara. Our country had few college creative writing courses at that time and even fewer writers’ conferences. SBWC is in its 41st year and now owned by Monte Schulz, son of cartoonist Charles Schulz.

Conrad pulled together good friends, including top best-selling authors such as Ray Bradbury, Alex Haley, and James Michener, to speak. And that was just for the first year in 1972. They and the many others gave of their time to discuss and support new and growing writers. By now, the featured speakers list looks like a who’s who of 20th-century American literature.

For opening night of the conference, Conrad would leap onto the stage, wearing, say, tennis clothes. His wardrobe might have been Brooks Brothers out of San Francisco, but his style was whatever he felt like putting on. He welcomed us by pointing out some of the celebrity writers in the audience — always Ray Bradbury as the opening-night speaker. When he read a sampling of previous winners from the annual contest The Worst Opening Sentences, he laughed harder than anyone there. Always there were more stories, some new, some heard at previous conferences, some with factual rearrangement.

Attendees have long tried to put a finger on what made SBWC zing besides a heady lineup of authors/speakers. Students paid to give up a week from work to focus on high hopes and elusive goals like getting published. Why? Perhaps it was Conrad’s laid-back style combined with Mary Conrad’s efficient organization. Workshops on 20 or more topics ran nearly around the clock. Conrad was at the Miramar campus much of that time, ending the evening in the bar with drinking buddies or students. What interested him most was the person’s writing or what books they had read, he himself a voracious reader. His computer-like mind effortlessly recalled titles, authors, and even opening lines.

Perie Longo (former poet laureate) said, “He believed in the power of the written word.” Conrad formed SBWC to create writers and watch them grow. Thousands have passed through that one incredible week. Some have made it big; some write for their own pleasure. He included us all in the circle of writers, and nothing inspired us more. From celebrities to “newbies,” everyone attended SBWC to be with other writers. That attitude originated from Conrad. It gave the week a high quotient of camaraderie.

The SBWC will go on even without Conrad hanging around telling his stories, the same-old or new ones, or telling us we really are writers; and what a legacy he has left us and Santa Barbara.