“The most maddening and the most lovable person who ever lived,” in the words of his dear friend, was Eric Cole Kitchen, my dad. Often, the most enchanting of us arrive in the most complex of packages. We could spend the rest of our lives trying to unpack it, but for now we will let him go.

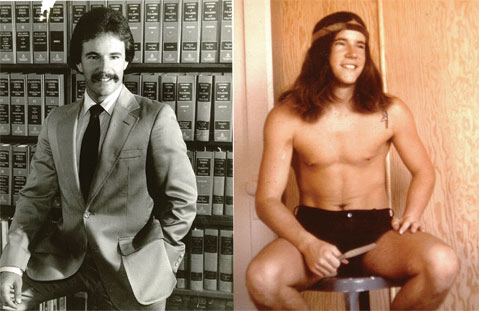

In our childhood, my sister Camille and I often shared our dad’s stories with our friends, not because we felt obligated to, but because they were genuinely strange and wild — the kind teenagers like. The line between fiction and reality was never quite clear. “He drove backward for a mile,” we’d say, and, “He used to be a pirate at sea.” In truth, he spent the majority of his adult life as an attorney, but his love for adventure and risk-taking would have made him an excellent sea captain had he been given the chance.

My dad’s magnetic personality can be attributed to his remarkable gift for conversation, especially with strangers. It wouldn’t be unusual for him to engage with a Rite Aid employee bagging his toiletries on the subject of quasi-stellar radio sources.

Of course, he had practical uses for his talents, as well. “Whereas most lawyers were formal and abstruse and mechanical, Eric was smooth, lucid, even funny,” recalls Garrett Morrison, a family friend who interned one summer for the Santa Barbara District Attorney. Garrett read many transcripts as an intern and recalls reading the bracketed word “[laughter]” after one of my dad’s particularly charming one-liners in the courtroom. “Apparently Eric had cracked everyone up,” he said. “In all my hours poring over transcripts that summer, I never saw anything else like it.”

Over the last two weeks, in the emails my sister and I receive about our dad, every one of his acquaintances interprets him uniquely. To one person, he was the life of the party; to another, he was a spiritual, mysterious soul; to others, he was an ethical scholar. Tirelessly curious, he wanted to fully immerse himself in the many frames of mind that surrounded him, so much so that we all understand him differently.

Perhaps my dad chased after the limelight most in the late 1960s and early ’70s, a time when he was known as the inimitable “Eddie Kitchenetti” who lived on Del Playa Drive in Isla Vista. In nearly every photograph of him as a student at UCSB, he is shirtless, long-haired, and beaming. His oldest friends tell stories of their reckless nights together, staying up until dawn trying to “uncover the secrets of the universe.” Even as he started to outgrow the Kitchenetti name — earning high marks in law school at Hastings, starting a law firm, and marrying my mother — his appreciation for the phenomenon of nature never left him. “Did you know there are more stars in the universe than there are grains of sand on this earth?” he would ask me as we sat on the beach. I always assumed he was lying.

Our dad was the one who, on rare occasions, picked us up from school with his car windows rolled down, blasting Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” full volume amid a long line of minivans. He also loved to plug his nose and speak with a horribly nasal voice whenever he made restaurant reservations. And yet this same man, who used to push me into the pool with my clothes on, also buried my pet rat with me when I was in the 1st grade. As I stood there, sobbing and completely devastated over the loss of my favorite creature, I looked up and saw that he was crying, too.

Most of my conversations with my dad over the last five years centered on his love for yoga and meditation. This helped bring us back together again after several years apart. He often expressed his desire to teach enlightenment and peace, something he thought was lacking in the field of law. After his death, as we collected his belongings, we came across a suitcase full of informational DVDs on the subjects of meditation and enlightenment. In tears, we exclaimed that he must have had his bags packed.

This past Sunday, I met up with some friends of my father’s at one of his favorite bars to celebrate his life, which ended with a heart attack in late May, when he was 62. I saw old friends of my dad’s who remain a central part of my childhood memories and others, who became close friends with him 10 years ago, whom I had never met. Some of us, including myself, had been estranged from him at different times in his life — a few in the beginning, some of us in the middle, and more in the end. And yet all of us were forever changed by his magic, each for completely different reasons, no matter what time in his life he entered and left our own. Beyond his mystery, his love, and his suitcase, he left me with the ability to see beauty in that kind of disjointedness, in the fragmented universe pulling apart and coming back together again.