Dr. Larry Agenbroad, considered by many to be the world’s preeminent mammoth paleontologist, has died at 81. The loss to the community is enormous. Most of the articles on mammoths written over the past several decades were either authored by him or referenced his work. His teaching and mentoring were likewise renowned. Beyond that, his friendship and zest for life touched many. For almost two decades, before declining health brought his visits to a close, his work in the Channel Islands made him a familiar presence in Santa Barbara.

Larry held a PhD from the University of Arizona in geology. For 25 years, he was professor of geology and paleontology at Northern Arizona University. Although he excelled there as both teacher and researcher, two of his greatest contributions were elsewhere.

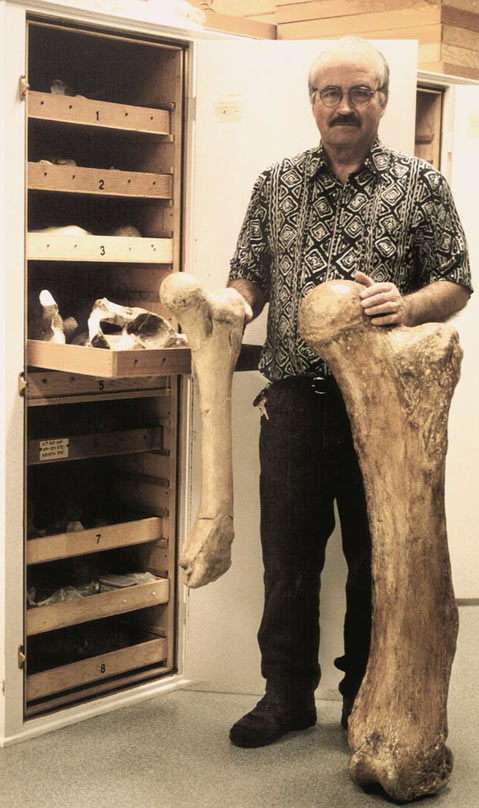

In 1974, Larry was called when a mammoth tusk was found by a developer in Hot Springs, South Dakota. Further excavations yielded much more material, which led to the creation of the Mammoth Site at Hot Springs. Larry served as its director for 40 years, stepping down only last year. Today, the site (which is a Pleistocene sinkhole) is acknowledged to have the highest density of Columbian and Woolly mammoths in the world, the excavations of which have all been left in place. It has a major museum, a large staff, and an ongoing research program. Most of the world’s great mammoth paleontologists have passed through the site, as have generations of students and colleagues whom Larry mentored.

Larry came to work in our part of the world in 1994, when a nearly complete fossil pygmy mammoth (Mammuthus exilis) skeleton was found on Santa Rosa Island by Tom Rockwell, a geologist at San Diego State University. Fossil pygmy mammoth material was known on the Channel Islands as early as 1856 and first described in the paleontology literature in 1928. Subsequent sporadic collections were made, including those by Dr. Phil Orr, of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, in the 1940s and 1950s. (Orr also found the famous Arlington Springs Man, one of the oldest documented human presences in the Western Hemisphere).

Prior to the 1994 find, the material had not been well studied. Dr. Agenbroad changed that. From 1994-2008, he found an additional 380 locations for pygmy mammoth material on San Miguel, Santa Rosa, and Santa Cruz islands. Pygmy mammoth fossils became rock stars, and Santa Rosa Island was ground zero; it had the highest density of pygmy mammoth material in the world. Walking up a canyon with Dr. Agenbroad was truly incredible; it often produced an almost running commentary — “there’s a tooth, there’s a rib, that’s part of a mandible, there’s part of a tusk.” As the mammoth material was dated, further dating was performed on the Arlington Springs Man. The result was the tantalizing possibility that humans and pygmy mammoths may have been contemporaries on the Channel Islands.

Larry also worked throughout the west and in Siberia, where he was one of the few non-Russian investigators to participate in the excavation of an intact, frozen mammoth. The frozen fur was defrosted with hair dryers, and Larry was able to subsequently boast that “it was my first opportunity to pet a mammoth.”

Dr. Agenbroad’s seminal accomplishments at Mammoth Site and on Santa Rosa Island were a reflection of his great passion for paleontology and boundless, infectious enthusiasm. I doubt that he would have considered that he ever “worked” a day in his professional life; it was all fun, even in an era when the trials and tribulations of doing field research were much greater than they are today. He taught and mentored with gentleness and humor, and he was generous of spirit. My wife, who has no background in paleontology, accompanied us on a Santa Cruz Island trip prospecting for mammoth material. Larry gently maneuvered her so that the first “find” of mammoth bones was hers.

My last time in the field with Larry was a few years ago on Santa Cruz Island. An apparent mammoth tusk had been found, and Larry called in, only to identify it as a fossil baleen whale mandible. My involvement began with an evening call, no identification from the caller but a growled, “Chuck, it’s not a mammoth tusk; it’s a baleen whale mandible. Get your butt out here.” I spent the next two days on Santa Cruz with Larry and Don Morris, archaeologist for Channel Islands National Park. On the second day, after the excavation was finished, we sat at the site waiting for almost two hours for the helicopter to take us off the island. I had the rare privilege of listening to Larry and Don, two great researchers and world-class raconteurs, swap stories of their experiences all over the west. That day remains one of my most delightful experiences in a lifetime of Channel Island trips.

Larry’s wife, Wanda, was his constant companion in adventure and life from high school onward. She frequently accompanied him into the field and had a zest for exploration equal to his. She ran the Colorado River three times. Sadly, she slipped away 10 weeks after her husband’s death.

Larry’s death is a great loss, as is Wanda’s. The tears have faded, but there remains a glow in the eyes of friends and colleagues at the mention of his name. He influenced, and was loved by, all whom his life touched. That’s a pretty good legacy to leave. Godspeed, old friend.