From deep roots in California’s history and soil, bred in an archetypal, pugnacious ranching family where everybody knew better than everybody, J.J. Hollister was known as a deft diplomat and renowned raconteur.

He grew up on his family’s storied Santa Anita Ranch, stretching along 17 miles of quintessential California coast, a pristine wilderness populated by wild animals, his grandfather’s white-faced Herefords, and vaqueros with Spanish names like Ortega, Pacheco, and Guevara. To the fiefdom’s north, the rocky, chaparral-carpeted Santa Ynez Mountains rose at Gaviota Pass and then faded west into Point Conception; on the south, channel waters shimmered past the kelp line to distant island scrims.

In the 1860s, his great-grandfather W.W. Hollister, together with business partner Thomas B. Dibblee, bought the coastal ranch from the Ortega family, Spanish soldiers who’d settled there in the 1790s. Their partnership, with Albert Dibblee, Thomas’s brother, ultimately included the coast ranches and the Lompoc, Mission Vieja, Espada, San Julian, Salsipuedes, and Las Cruces land grants — over 150,000 acres of Santa Barbara County.

By the early 1960s, after Hollisters had been embedded on the coast for one century and four generations, most of the family wanted to sell the Santa Anita Ranch, as well as the nearby Las Cruces, the Winchester near Goleta, and the Salsipuedes south of Lompoc — over 30,000 acres in all. Others argued against selling the family’s very identity, a venerable legacy originated by patriarch William Welles Hollister — the man who Americanized Santa Barbara in the late 19th century. The family spun into dysfunction. According to J.J.’s cousin, Princeton professor Lincoln Hollister, there were too many Hollisters “trying to feed at the trough of a marginal cattle operation.”

J.J. described the coast ranch — now called the Hollister Ranch — as the family’s deadman. (A “deadman” is a large buried rock attached by wire to the corner post of a wire fence that prevents the post from leaning by counteracting the pull of the fence wire.) He wrote to his grandfather Jim in 1960: “You identified our name in California soil. You brought your family up with the soil … the raison d’etre of our existence … the ranch was a ‘deadman’ which kept the post straight and strong, and at all times doing the job well — as was its original purpose and duty. But take away the deadman and the fence falls from the pull by the barbed wire in all directions, straining to relax the tension and get free. Our family has been relaxing for a long time — gradually pulling up the deadman.” He was disturbed that some family members would choose freely to “hoe up [their] own roots” and predicted the family would “wander like an abandoned calf” when the ranches were sold.

Nevertheless, J.J. — then 28 — concluded the best collective decision was to sell. He honed his natural diplomacy engaged in family meetings where he “walked a tightrope, sitting down with everyone as a friend” amid the “yelling and screaming of a poison environment,” deftly urging sale of the ranches between herds of “stray Hollisters,” according to cousin Lincoln. J.J. worked with his aunt, Jane Hollister Wheelwright, who had the decision-making voting power by virtue of a trust created by her father, Jim, to the dismay of her brothers. Jane decided it would be folly to keep the ranches.

In 1965, real estate developers purchased the Santa Anita with plans for three pleasure boat harbors and 25,000 residents. But due to death and bankruptcy of successive owners, it was instead divided into 100-acre ranchitos and remains in large part a cattle operation.

After the sale, J.J.’s deadman became the 780-acre Arroyo Hondo Ranch east of Gaviota, which his grandaunt Jennie purchased in 1908. There, Vicente Ortega lived in his grandfather Pedro’s adobe home, built in 1842 with the help of a Chumash man, Silverio Konoyo. Vicente was an acclaimed vaquero whom J.J. knew from his work with Jim Hollister, and J.J. gave Vicente free use of Arroyo Hondo until his death in 1984.

Forty years after the sale of the Santa Anita, J.J. used his diplomatic skills in his proudest civic accomplishment. By the 1980s, land trusts had emerged as a way to conserve great swaths of property. J.J. convinced a large family of step-cousins to sell the Arroyo Hondo to the Lnad Trust for Santa Barbara in 2001, putting his charm on full to help the trust raise the funds. He wanted the untrammeled canyon preserved and not developed in what he once described as the American tradition of “gobble, gulp, and go.”

In 2011, J.J. persuaded the diverse Hollister heirs to donate their last common landholding, 2.8 acres of the former Vista del Mar school near Gaviota, to a marine wildlife institute for rehabilitating injured marine mammals, concluding at last his family’s 150-year land-based plutocracy.

J.J. collected family stories and photographs. His cousin Doyle Hollister recalled that J.J. was “the quintessential heritage carrier … he passionately and soulfully carried the torch” of the Hollister family. And his friend Scott Newhall, descendant of another 19th-century California land dynasty, commended him as “the real living history … there was no person more a part of Santa Barbara than J.J. Hollister.” He wrote two books, Gaviota Boy and Going West With the Hollisters. There were many Hollister stories to tell.

Patriarch W.W. Hollister first came to California from Ohio in 1852 on the Oregon Trail. In San Juan Bautista, he met a survivor of the Donner Party, Patrick Breen, who advised him that the Pacheco family’s 35,000-acre Rancho San Justo was for sale. On a second trip west with his brother Hubbard and sister, Lucy, W.W. formed a partnership to buy it with Llewellyn Bixby and his cousins Thomas and Benjamin Flint, who, like the Hollisters, were driving sheep to California. The families formed a partnership to buy the San Justo in 1854, which they soon after divided in halves. The Hollisters sold their half of the San Justo in 1868 to a farmers’ cooperative, which platted a new town, naming it Hollister. The Bixbys became neighbors again when they bought Point Conception, Cojo, and Jalama, in addition to very large ranches near Long Beach and, providentially, Signal Hill. Hubbard’s daughters married into other California families — Banning, Stow, and Jack. Another brother, Albert, came west in 1872, establishing the Fairview Ranch in Goleta.

W.W. also purchased 5,000 acres in the Goleta foothills known as the Tecolotito in the late 1860s from the Den family. He renamed it “Glen Annie” for his wife. The ranch was the region’s showcase, boasting a mansion and a veritable botanical garden of exotic flora. The street that led to the ranch bore his name — Hollister Avenue. From this Goleta ranch, based on his financial resources from wool and land, Hollister helped finance and establish much of Santa Barbara during its period of Americanization — Santa Barbara College, the public library, a steam laundry, the Arlington Hotel, Stearns Wharf, Lobero’s theater, and the Morning Press.

W.W. and Annie’s son John James Hollister Sr., “Jim,” was born in 1870. He became manager of the Santa Anita in 1910, taking over from his older brother, William Wallace, who gave the ranch its iconic WWH brand and later died in a mule wagon accident in Napa. Another brother, Stanley, died next to Teddy Roosevelt on Cuba’s San Juan Hill in 1898 as one of the Rough Riders in the Spanish American War.

Jim was elected to the State Senate in 1924. He ran again in 1932 but lost to his cousin, Edgar Stow. In 1936 the cousins again ran against one another, and this time Jim won, having switched to the Democratic Party. Later, Jim’s son Jack, J.J.’s father, was appointed to the State Senate in 1955 after Clarence Ward’s death. Jack was then elected in 1956 and 1960. Both Jim and Jack died in 1961, saving themselves from the ongoing family controversy over sale of the coast ranches.

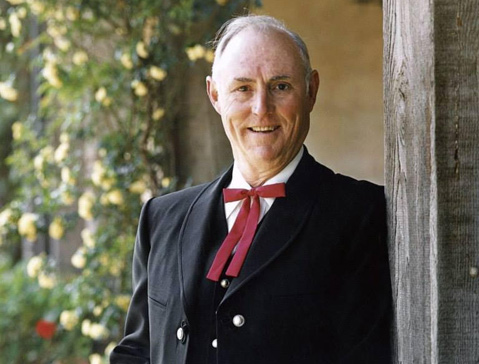

John James Hollister III (“J.J.” to friends; “Jimmy” to family) was born in San Francisco in 1932 and grew up with his sister, Cynthia (“Cinnie-wee”), on the Santa Anita, an hour’s drive on a winding dirt road west of Gaviota Beach, and later on Goleta’s Winchester Ranch. He was fond of sharing reminiscences of their idyllic childhood on the remote cattle ranches, where the children rode waves naked and rode ponies — J.J.’s was named Indita — along miles of deserted beach. Their friends were native animals, some of which became pets. An orphaned mule deer fawn, “Mustard,” rode in the back of ranch pickup trucks like a dog. A pig, “Chipmunk,” lived in the ranch house. A raccoon, “Freddie,” joined a family vacation by car to Northern California. Their favorite pet was a bobcat, “Baby,” which slept on Cinnie-wee’s bed. J.J. also developed an interest in birds, peering into “every place where a bird might be.” He said, “I would try to find their nests and learn something about what their eggs looked like, why the birds nested where they did. I learned birds, and I saw where they could live and how they survived.”

And he learned riding, roping, and caring for beef cattle from the Spanish-speaking vaqueros, as well as his lifetime penchant of pronouncing “Gaviota” as in Spanish, the accent on the “o.”

When J.J. was finishing high school at Cate in Carpinteria, he wanted to enlist in the Marines and fight in Korea, but he wasn’t old enough without written parental permission. When his father refused to sign, J.J.’s mother did. He saw combat, serving as a “tanker” in 1952-53 and driving an amphibian tractor. Jack’s anger over his son’s surreptitious enlistment dissolved when he learned J.J. could attend college on the GI Bill. J.J. went north to Stanford, where his grandparents Jim Hollister and Lottie Steffens had graduated with Herbert Hoover in Stanford’s pioneer class of 1895.

While at Stanford, J.J. married classmate Virginia Castagnola of Santa Barbara. They had three children: George, Cate, and Scott. After the couple divorced, J.J. married Barbara “Babs” Benning in 1970 at the Arroyo Hondo, which added Babs’s four children, Bill, Matt, Sara, and Joe, to the family. Babs died in 2013. Together they leave seven children, 15 grandchildren, and nine great-grandchildren.

After finishing Stanford in 1958, J.J. graduated from Cal’s Boalt Hall in 1961 and returned to Santa Barbara. Family background and social skill prompted his acceptance into old-line community groups. First, in 1962, he was elected to the Society of Los Alamos, composed of descendants of 19th-century Californio and American ranchers. J.J.’s granduncle, Clinton Hale, had been a charter member in 1910. J.J. presided as toastmaster at the Society’s annual ranch barbecues for many years, telling jokes and recounting stories about the members’ families, some of which were true. The great-grandson of his great-grandfather’s business partner Thomas Diblee, Jim Poett, still manages his family’s Rancho San Julian, sharing a boundary and much common history with the Hollister Ranch. Poett said last week: “For myself, and my family, just the fact that a partnership that started during the Civil War remained viable for as long as it did, and spawned a family friendship among neighbors and colleagues for well over a hundred years, is noteworthy. But more than that, J.J. truly was the most charming and honest … bullshitter I ever knew.”

J.J. joined the Santa Barbara Club in 1963, where his grandfather and two granduncles were charter members in 1892. He continued as an active member through his death on January 14, a few weeks before his 84th birthday.

Garrett Van Horne of Goleta’s Stow Ranch nominated his cousin J.J. in 1969 for membership in Rancheros Visitadores, established in 1930 as Santa Barbara’s rendition of San Francisco’s Bohemian Club. Rancheros is composed of fraternal camps, and J.J. was welcomed into the notorious “4Q” camp, which, according to longtime member Sandy Power, was an offshoot of a group of weekend recreational riders and goat-ropers in Buellton from the 1920s. The camp described itself in 1955 as the most “hospitable, disreputable, generous, arrogant, talented, low brow, intellectual group of nonconforming public-spirited members of any camp of Rancheros.” Power recalls J.J. as the 4Q camp raconteur and historian: “He amused us with wonderful stories, driving a mountain wagon and participating in our bull frog races, which gave us a big laugh.”

One of J.J.’s greatest honors was serving as El Presidente of Old Spanish Days Fiesta in 1992. There he volunteered with fellow Ranchero Bill Luton Jr., an Ortega descendant and scion of the Den family, which battled with the Hollisters in court for 14 years over ownership of the Glen Annie Ranch, a fight known as Santa Barbara’s legal drama of the 19th century.

Luton enjoyed working with J.J., despite their ancestors’ famous fight: “He loved history and worked for Fiesta to be true to its roots,” which go back to the 1920s. “If J.J. did something, he was 100 percent behind it. He worked hard for Fiesta just like he worked hard to get the Arroyo Hondo to the Land Trust.” When asked recently if he’d proclaim the Den-Hollister feud to be over after 125 years, Luton grinned: “J.J. was the greatest guy, and he was pretty well versed in local history … for a Hollister.”

The law firm that bears his name, Hollister & Brace, was started in 1966 by J.J. and his friends Bill Brace and Bob Angle. Attorney John Poucher spent his professional life there and remembered J.J. as a “happy character … The hardest thing about working with J.J. was to go to lunch with him. It took at least a half an hour to get from the front door to our table because he knew everybody and stopped at every table to visit,” Poucher recalled. “He was a fantastic rainmaker.”