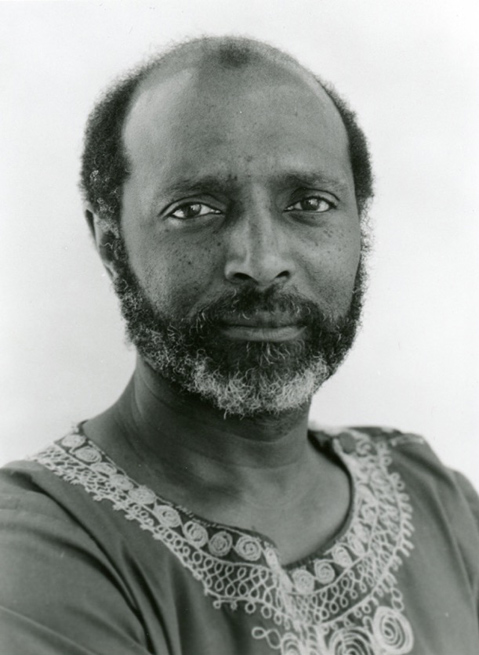

Cedric James Robinson was born in Oakland, California, on November 5, 1940. He was a sickly baby who, the story goes, was kept alive when a great aunt fed him “potliquor,” juice from the greens she was stewing. The little guy had to fight to survive, and maybe that foretold his modus vivende for the next 75 years. Surely he also learned that that collaboration was a necessity and that a sense of humor was essential. He often said that there was great value in the struggle, regardless of the outcome.

As a child growing up in Oakland, he experienced both American apartheid and the intellectual nourishment provided by black teachers and mentors who instilled in him a love of learning, of reading. He continued his education at Berkeley High School and then at UC Berkeley, where he studied anthropology. Outside the classroom, his political activities in pursuit of civil rights and opposition to U.S. foreign policy would lead to a one-semester suspension from the university. He and others organized a campus demonstration against the attempted U.S. invasion of Cuba in 1961, and they were penalized for failing to give authorities 48 hours’ notice. His retort, an unsuccessful defense, was that the U.S. government had not given citizens 48 hours’ notice of the invasion.

This suggests the arrogance of a 20-year-old, and Cedric could be arrogant but, in my experience, only with those who presumed they were entitled. It was an arrogance born of his refusal to be cowed by the power holders, be they local police demanding to know what was in his briefcase or academics who considered the academy their rarified preserve. Cedric would receive his PhD from Stanford, but only after a fight. He had the temerity to critique the “giants” of political science, many of whom were Stanford faculty. The Terms of Order, just republished after 30-plus years out of print, was based on that critique.

Almost immediately after we arrived in Santa Barbara, in 1979, Cedric began to build ties outside the university. These included the creation of several historic timelines of the black community, speaking with Gray Panthers and others about the depredations of U.S. foreign policy in the Third World, and the creation of Third World News Review, first on radio and then television, to share those views with the community. He participated in antiwar activities and the formation of the Campaign for International Diplomacy, addressed newly inducted U.S. citizens, held board membership on the local ACLU, and opposed the building of a new jail here, a matter still up for debate.

To be sure, Cedric never suffered fools gladly, but he would engage most people with endless patience or at least until it became apparent they weren’t seriously interested in progressive social change. On the other hand, he always advised students and people of color of the inherent risks in getting arrested, since getting in was always easier than getting out.

For all his public presence, he was a very private individual and cherished me and his daughter, Najda, and now his grandson, Jacob, unreservedly. Although he and I might have verbally tussled, his patience and love for Najda and Jacob was unbounded. —Elizabeth Robinson

•••

I remember looking casually at my emails and then, with stupor, reading one from Elizabeth announcing the quiet passing of my friend, Cedric, my colleague of more than 36 years. The emblematic figure of our department, loved and respected by many, was no longer. I was terribly upset, but an upswell of memories suddenly submerged the tide of sorrow that a few moments earlier had engulfed me.

I remembered his smile and his piercing gaze. That inquiring gaze that so efficiently cracked the mirror of your soul, a gaze that had become a powerful weapon against hypocrites and sycophants, so prevalent in our environment. I remember experiencing his powerful handshake and incisive gaze when he first visited our campus. Both were intimidating yet reassuring, and I quickly discovered they were the traits of a splendid mind serving a man possessed by passion. A man dedicated to the idea of social justice in a moral world. Right away I became an unconditional Robinsonian, and together we applied ourselves to redressing as many evils as we could.

During an action when students demanded a more just and relevant university, I remember his eloquent speech in front of the Academic Senate, when he responded to those who claimed only Western Civilization should be taught to students, that “Western Civilization was neither.”

I also remember us driving to Los Angeles to testify in defense of a Chicano professor who had been unjustly denied a position on campus. As we entered the room, we saw that all the administrators had come to defend the university. I can still hear Cedric, with his famous side smile, whispering in my ear at the sight of such a spectacle, “Here goes our next promotions.” With contained laughs, it reminded us of the tale in which Brer Rabbit was judged by a court entirely staffed by Foxes.

We had pretty good times together, whether on campus or outside campus, taping Third World News Review. If our discussion was at times passionate, our argumentation always seemed complementary. On the show, my French accent and usage always seemed to amuse him. I remember him waiting in ambush for me to ask the staff to “pass the film.” With a grin, he would always correct me with the same sentence: “We only pass gas, but we show movies.” We would laugh, and I would move on to my next awkward gallicism.

Yes, Cedric, I will truly regret our little moments of complicity when thoughts were more important than words. If I mourn your absence, I will always feel blessed to have been part of your trajectory, and I am honored to have been the friend of one whom I consider to be the most influential thinker of our times. —Professor Gerard Pigeon

•••

People may forget the things you create, and people may forget the things you say, but people never forget how you make them feel: This is how I came to know Cedric Robinson. To be in Cedric’s presence was to be in the presence of someone who truly saw you, saw your potential, and saw your passions, not solely from an ally’s position but from a position of sincere solidarity. He established a dialogue that enabled students and colleagues to challenge ourselves to be and do better, and we will never forget.

During a hunger strike at UCSB in 1989, some staff and faculty supported students who put their lives on the line to call attention to institutional racism — only a change in curriculum could stem its growth — and to the need for more diversity. The 15-day strike came after a year of inaction on a plan presented to the chancellor. Cedric joined the students’ fast for three days. Six days later, students at all UC campuses united in support. The Academic Senate agreed to vote. Just as the creation of Black and Chicano studies grew from the occupation of North Hall in 1968, so today’s Asian-American and Native-American studies, MultiCultural Center, and general-ed ethnic studies requirements resulted from this work and protest and struggle. Each of these changes to the status quo came to strengthen the university’s future.

One of Cedric’s consistent lessons was to interrogate the work of the media. If one finds the media is less than honest, then become the media. If the representation of one’s story/people is less than honest in Hollywood — write and perform your own history. In a letter, Cedric wrote that his earliest intentions were “to re-open a door to a special universe where justice reigned as historical practice; as a constant inspiration for present conduct; and as a realizable project. My key was to be race studies, but I have always supposed there were others, fashioned from the resistances which are inevitable companions to oppression.” Cedric’s scholarly work and his commitment to freedom prove that the world is better for our ability to change, as are we all. —Dr. Marisela Márquez