Willie Rodriguez: The Retirement of a Citizen

A Thoroughly Santa Barbara Story of Family, Commerce, and Barbering

Willie Rodriguez, a working-class Santa Barbara native born on the Dos Pueblos Ranch 85 years ago, retired last week after working at Willie’s Barber Shop on Figueroa Street for almost 60 years.

His retirement is akin to the Courthouse closing or Stearns Wharf falling into the ocean. Willie is so authentic and so legendary that it hardly seems possible that there could be a downtown Santa Barbara without him.

But Willie’s retirement is not a story of loss. This is not a lament about the Santa Barbara that once was. Willie may be retiring, but the shop and the family legacy that he built does not end. Willie’s oldest son, Gilbert Rodriguez Sr., has worked with him for 13 years and will continue at the shop. And Willie’s own chair? That’s being taken over by grandson Gilbert Rodriguez Jr.

What’s more, two of Willie’s granddaughters are now studying for their beautician licenses and may also start taking shifts soon, bringing female barbers into the shop for the first time. That means Santa Barbara could easily see another 60 years of flattops and wash-and-wears — and since about 10 years ago, fades — delivered with a smile, some good gossip, and a caring ear by members of the Rodriguez family.

As such, this is that all-too-rare story about the building of a living link between Santa Barbara’s agrarian past and a future in which solid legacy businesses — and the communities that they create — persevere in times of rapid change. Like so many small municipalities worldwide, Santa Barbara has witnessed many of its cherished shops lose their viability to escalating rents, big-box stores, and the convenience of shopping online. Music stores, bookstores, and record stores are dropping one by one. Thankfully, for the Rodriguez family and the rest of us, you still can’t get a haircut delivered overnight by Amazon.

And while there are plenty more fancy old-time barbershops in Santa Barbara, ones that are clean and shiny and turn a dime on their classic ambience, Willie’s is just Willie’s, a regular joint with empty soda cans in the front window and three old chairs on the sidewalk where the barbers take their breaks. Judges and sheriffs sit side by side with street people, the waiting bench is always stocked with newspapers for passing the time, a man’s haircut is still just 18 bucks, and after a cut is complete, Willie still uses a vacuum cleaner to lift the fallen hair from a client’s shoulders.

Gilbert Sr. explains the shop’s appeal: “It’s a no-frills place. We’re not going to try to sell men anything, and sometimes we don’t even talk. Sometimes the man will fall asleep when we are cutting his hair ’cause he’s so relaxed. And then there are times they come in with all kinds of concerns, and so we talk a lot. Sometimes maybe they just lost someone in their family, and so we feel that with them. It’s a place that’s unusual because there you are, inches away from another guy, talking about personal things, sometimes life-changing things, which doesn’t happen anywhere else.”

And even though Willie’s will go on, there will never be, there could never be, another Willie.

The last time Willie got sick was in 1957. In the nearly 60 years he worked at the shop, he took a few days off, but he never took a real vacation. He had seen the world while in the U.S. Air Force, between 1950 and 1955, and after he started at the shop in 1957, he thought to himself, Okay, time to settle into a routine. And this is what he came up with: Before his five-day workweek would start on Tuesday morning, he’d stop and get five breakfast burritos. He’d get to work at around 6 a.m. and put the burritos in the fridge. Then he’d walk a block and half for a cup of coffee and a piece of Mexican bread, bring them back to the shop, sit in his barber chair, eat the bread, sip the coffee, and read the Santa Barbara and Los Angeles papers.

Then he’d turn the chair backward, put a blanket over himself, and fall back asleep for an hour, until Gilbert Sr. showed up at around 8:45 a.m. Then he’d gather his barber paraphernalia together, and at 9 a.m. he was on his feet, wrapping the paper collar around his first customer’s neck and getting to work. At lunch — every day — he ate one of the breakfast burritos. Then he went back to work until 4:30 p.m., swept up, locked the door, and drove home. After his wife, Celia, passed in 1999, he altered his routine a bit. Before going home, he’d grab a sandwich.

He made all of his phone calls from the shop landline because he didn’t have a phone at home and still doesn’t own a cell phone.

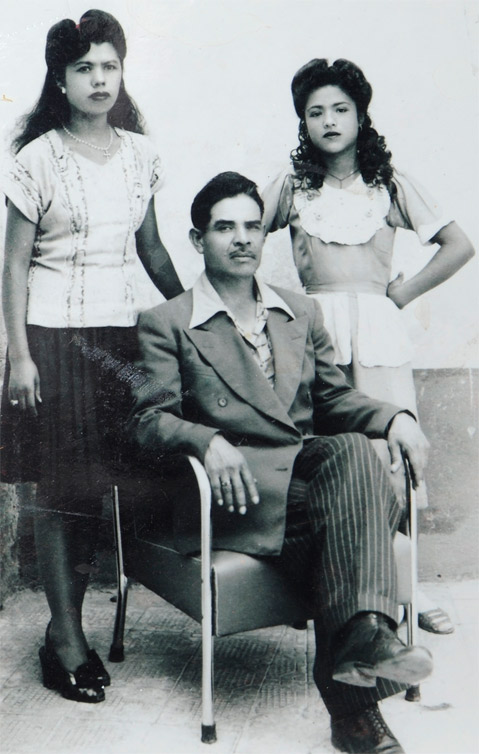

Willie’s father, Jose Rodriguez, immigrated to Santa Barbara in 1917 from the Michoacán region of Mexico. He met his wife, Rosario, a few years later, and they settled at the Dos Pueblos Ranch, a Spanish land grant parcel set right on the ocean 20 miles north of town. He worked avocados and beans and fathered eight kids, five of whom — three boys and two girls — are still alive and living in Santa Barbara. All except Willie are now over the age of 90.

After a long day of farming, Willie’s father would attend night school to learn English, and when Willie was 11 years old, he moved the family into town. Willie attended public schools, graduating from Santa Barbara High in 1950. Along the way, he worked odd jobs at classic old places such as the Blue Onion, where he was a dishwasher. He enlisted in the U.S. Air Force in 1950 and served five years as a mechanic, rising to airman first class. He traveled to places such as the Philippines and Hong Kong, was discharged in 1955, and moved back to his hometown. All three of his brothers also served in the military.

After the service, Willie went to barber school. He landed his first job in 1956, at a now-closed State Street establishment named Frank’s Barbershop, owned by proprietor Frank Herrera. In those days the barbers sharpened their razors with stones and mostly offered crew cuts and flattops, although men in those days had also begun to discover more fashionable cuts like the Princeton, the boogie, and what was known as the flattop with fenders.

Within a year, Willie had moved to his current location on Figueroa Street between State and Chapala. He began by charging $1 a cut. He was naturally introverted, he said, but “learned to talk.” He kept up with sports and honed his trademark conversation starters: binders with old photos of Santa Barbara, and a pair of foot-long hedge clippers, which, if the conversation really lagged, he could employ as a gag.

Although the shop was cleaned up by request of his landlord a year ago, it historically had money from international customers tacked to the wall, athletic trophies earned by his kids on the old cash register, an Our Lady of Guadalupe figurine, model airplanes, a sword Willie brought back from the Philippines, a big hairball in a shaving mug, a painting of the Tetons that originally hung in the Rodriguez living room, a toupee to place on customers who requested a haircut that made them look like a movie star, and lots of gifts that had been brought in over the years. It felt like someone’s living room.

In 1955, during Santa Barbara’s signature celebration, Old Spanish Days Fiesta, Willie met a strong, loving, pretty young woman named Celia. They were both celebrating on State Street and taking stock of those they might find attractive and suitable, as young adults have for ages. In their case, the stars aligned. Within a year, Willie and Celia had married. They found a $50-per-month loft apartment downtown, where they lived until they had their first son, Gilbert, and then Willie bought a house on the Mesa that he still owns. They had three more children and raised them there.

All four of Willie’s kids still live in Santa Barbara. Collectively, they’ve had 14 children and eight grandchildren. Like Willie’s Barber Shop, the Rodriguez family is itself now a Santa Barbara institution, one of the thousands of families here that don’t make the news and aren’t seen in the cafés, but who build their own close-knit world of integrity and support one day at a time. Willie’s may be timeless, but that’s undoubtedly because the business and the Rodriguez family were built on timeless values.

“Being Hispanic, we do everything together,” Gilbert Sr. said. “We hang out together. It’s just how we do things.” In addition to large, festive family gatherings for holidays, Gilbert Sr. said, his mom would organize a barbecue at their house every weekend in the days of his youth, a ritual that helped build trusting relationships within the family and with friends and neighbors. “My mom would call Willie at work on Saturday and say, ‘I need 300 bucks for the barbecue,’ and when he would get home, the place would be crawling with people,” he said. “People would just walk in and make themselves at home. That’s no exaggeration.”

The approach to living that nested in Gilbert Sr. and his siblings was this, he said: “Share love. Share what you have. Give what you have. That’s what we operated on.”

To that end, Willie’s Barber Shop has also been a way station for folks in that area who might be down on their luck. Even if they weren’t getting a haircut, neighborhood regulars were allowed to come in and use the phone if they needed it. Willie would give loans to people and not expect the money to be returned. Sometimes the loan would be a hundred dollar bill, and sometimes a lot more, no questions asked. Willie befriended a man who collects recyclables, so between customers, Willie could be seen out on the sidewalk picking cans and bottles out of a waste receptacle. Here was a successful businessperson who wasn’t beyond reaching into a garbage can to help out a neighbor who was trying to pull himself up.

Willie’s longevity and gentle ways made him something of an unofficial mayor, if not for all of Santa Barbara, then definitely for his block of Figueroa. Men who were just kids when they got their first cut from Willie are now bringing in their grandsons. It seems as if everyone who passes his front window looks in and gives a smile and a wave. He’s from the generation when men called men by their last names, and so that’s what he still does, with regular customers or neighborhood friends, calling out to them as they pass by, ribbing them about something. Hey, Welsh, you look like you’re slowing down. Hey, Jones, how’s the dancing going?

Willie took up hiking at age 77. He likes the Romero Canyon, Cold Spring, and Hot Springs Canyon trails. He goes up there on most Sundays. He’s not interested in slowing down. He’ll be providing cuts to customers who are housebound or in convalescent homes. But he said he’s also feeling that he doesn’t want to be in the shop anymore, full-time at least. “I used to be able to do the haircuts, and now it’s gotten so hard [that] it’s more of a job than I really want to do,” he said. “It was better when it was just a regular haircut. You take it off around the ears, taper the back, or shear cut the back, take care of the top, trim the neck, and it’s done.”

Willie himself admits that after almost 60 years, it won’t be easy for him to stay away — he’ll still be glad to fill in when needed or if his son or grandson need some time off. God knows that after missing only one or two days of work in decades of service, he deserves some time off, too. Gilbert Sr. reports Willie’s still in from time to time on his days off, putting in new lights or in some other small way improving the place. And truth be told, even though Willie officially retired in mid-July, he’s decided to come into work on Tuesday and Friday afternoons just to be there, for now, at least.

Which is in itself reassuring. It’s good to know that there will still be times when Willie will be at Willie’s. He’ll be watching the block of Figueroa that he’s been watching for nearly 60 years, honoring the value of that time and his own contribution to the place and keeping tabs on customers and the people who once relied on his generosity of spirit for their safety and livelihood.

And being with family.