Fight for 24th Congressional District

Carbajal and Fareed Duke It Out for 24th Congressional District

Things don’t get much hotter.

This week, President Barack Obama descended from the White House to endorse Salud Carbajal, the Democratic county supervisor now running to represent the South Coast in Congress. Historically, Obama has made a point to stay out of local races, but given the stakes involved, coupled with his surging popularity, he’s jumped in feetfirst, endorsing Democrats in 150 congressional and statehouse races.

In the other camp, no less a figure than House Speaker and Republican party leader Paul Ryan made an appearance in Santa Barbara this past weekend, executing a quick fundraising whistle-stop to exhort the faithful party to give ’til it hurts and send Republican Justin Fareed to Congress next year.

The race for the 24th Congressional District — which encompasses Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties, plus a tiny sliver of Ventura County — could set new spending records, shattering the $10 million ceiling. That’s partly because the 24th was singled out by major political handicappers as one of three genuinely competitive districts in all of California.

When it comes to personal history, life experience, style, and personal values, the differences between Carbajal and Fareed could not be more glaring. On hot-button issues such as abortion rights, gun control, banning oil development and fracking, minimum-wage increases, free college tuition, and the Affordable Care Act, Carbajal counts himself as emphatically in favor. Fareed, by contrast, not so much. A self-described voice of young millennials, Fareed talks the talk of fiscal prudence, tax burdens, overregulation, and crushing federal debt. Carbajal talks instead about making opportunities for “working middle-class families.”

With Carbajal and Fareed, the political is also the personal. These two candidates do not like each other.

BOMBS AWAY:

At a recent debate, the 51-year-old Carbajal sarcastically belittled Fareed — 28 — saying he had no experience to speak of other than playing high school football and working briefly — 14 months — for a Kentucky congressmember who resigned earlier this year in the wake of an ethics scandal. “I certainly hope you can do better than that,” Carbajal said, “if you want to hit the ground running.”

Later in the same debate, Fareed was asked if he could think of anything positive to say about Carbajal. “The answer,” he spat, “is no, I can’t.”

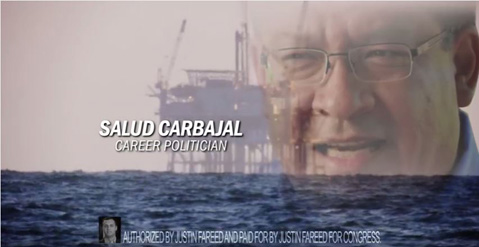

Both campaigns have deluged the airwaves with televised ads, but Fareed’s have been more aggressive. He has relentlessly attacked Carbajal as a self-serving, double-talking Democratic Party hack who voted to give himself multiple pay increases while not paying his own taxes and increasing the tax burden on others. He questioned how Carbajal could claim to be against offshore oil development when, in fact, Carbajal voted in favor of the PXP oil development proposed eight years ago. Carbajal said he was “appalled” Fareed would take such liberties with the facts, noting the PXP proposal had been resoundingly vetted and endorsed by the local environmental establishment because it would — among other things — hasten the shutdown of existing offshore oil platforms.

Carbajal’s ads have skewered Fareed for not renouncing Trump before the Access Hollywood videotape story broke and then distancing himself afterward out of political expediency. Recently, Fareed announced he is supporting neither Trump nor Clinton and denied ever endorsing Trump, despite telling the Montecito Journal shortly before the Republican convention that he had. “This is just ridiculous,” Fareed fumed at a recent debate. “You should be ashamed of yourself.”

DUELING TRAJECTORIES:

Carbajal, the youngest of eight kids, was born in Mexico and moved to the United States at age 5 with his family to the copper-mining town of Bagdad, Arizona. There his father worked in the mines, earning solid middle-class pay. Carbajal learned English almost effortlessly, spoke without an accent, and mixed easily with kids of all skin colors. Life, however, was anything but Mayberry. The copper mine shut down before Carbajal hit junior high school, and his mom — afflicted with debilitating rheumatoid arthritis — took part of the family to Oxnard. Not long after, one of Carbajal’s sisters committed suicide, shooting herself with her father’s revolver. Carbajal was in the next room and first to see the body. The family reunited, moving into public housing in La Colonia, one of Oxnard’s tougher neighborhoods. Smart, goofy, and socially agile, Carbajal did well in school and got along with kids from all the cliques. His father worked in the fields — so, too, did Carbajal in the summer months.

He was the first in his family to graduate from a four-year college: UCSB. Carbajal credits his parents and good teachers for this success. While at UCSB, Carbajal met his wife, Gina— who now runs Santa Barbara’s Special Olympics— on a blind date. “She must be blind because we’re still married,” he joked at a recent forum. They have two kids. After graduating, Carbajal enlisted in the Marine Reserves and trained during the first Gulf War, but his unit was never deployed.

Back home, Carbajal began working for the County of Santa Barbara. He and Gina soon bought a home on the Westside, getting into debt over their heads and had five IRS liens placed on them. By 2000, all had been paid off. Fareed’s campaign ads have jumped on Carbajal for endorsing increases in statewide income taxes and voting in favor of sales- and bed-tax increases at the county level, when he couldn’t pay his own taxes. Carbajal answered that his financial challenges are typical of many working families. Likewise, any votes to increase taxes required a majority of county supervisors to pass; most such votes were unanimous.

Were it not for the late 1st District supervisor Naomi Schwartz, it’s not certain where Carbajal’s career might have led. Respected and somewhat feared, Schwartz had emerged by the 1990s as the reigning Mama Bear of the environmental-Democratic establishment. When Latino activists noted that none of the liberal supervisors had hired any brown-skinned administrative staff, Schwartz asked Carbajal if he knew of anyone who might be interested. He was.

Under Schwartz’s mentoring, Carbajal got a crash course in constituent service. He worked hard, took pains never to upstage his boss, and put his innate affability to use, navigating the tug and pull of multiple conflicting agendas. Carbajal might not be the land-use wonk Schwartz was; few could be. But those looking behind his jovial façade discovered an unusually tough, shrewd, careful, and appraising person. He didn’t wave flags; he listened, and he made deals. He was good at it. It was equally evident that Schwartz was grooming Carbajal to fill her shoes. Only Congressmember Lois Capps, who endorsed him when he was first announced, would give Carbajal’s political career a bigger boost.

FOOTBALL AND THOROUGHBREDS:

Justin Fareed, by contrast, was born at Cottage Hospital and grew up in Montecito — the youngest of two kids. His father, Donald Fareed, is a famously gifted orthopedic surgeon; his mother, Linda Fareed, is equally famous as a whirling dervish in Santa Barbara real estate. She also focused her considerable energy on developing the family business manufacturing orthopedic knee and ankle braces. On the campaign trail, Fareed talks about “breaking down boxes” for the family business even as a young kid, eventually rising to vice president. Fareed’s mother’s family also owns a Kern County cattle ranch, going back three generations. On the campaign trail, Fareed frequently cites both in explaining why he believes the reach of government needs to be checked. Many small businesses, he says, cannot survive the gauntlet of government regulation and taxes.

At Santa Barbara High School, Fareed became an accomplished running back for the Dons football team and then attended UCLA and made the football team there, but an injury kept him on the bench. In his senior year, Fareed boasted, he was voted Most Inspirational Player.

After graduating in 2011 — majoring in international relations — he stuck around the football program as an unpaid coaching intern. Shortly thereafter, he stumbled into a paying staff gig with then-congressmember Ed Whitfield of Kentucky, Republican chair of the influential Energy and Power subcommittee.

There are multiple accounts as to how Fareed and Whitfield hooked up. One, favored by Fareed’s campaign, tells how he encountered Whitfield looking a little lost outside the UCLA locker room. Fareed struck up a conversation and helped him find his way. Whitfield, impressed, offered Fareed a paying position as legislative analyst. Another version — also from the campaign — suggests the Fareed family and Whitfield go way back, bonded by a common passion for thoroughbred horses. Federal elections records, however, indicate Fareed’s mother and aunt began donating to Whitfield — either directly or through his political action committee, the Thoroughbred PAC — as early as 2006, six years before Fareed started working for the former congressmember.

D.C. DYSFUNCTION:

Hired by Whitfield in 2012, Fareed said he saw firsthand the dysfunction in Washington, D.C. He quit, he said, because of the “zero-sum-game, winner-take-all” shortsightedness of a political system in which participants focus more on winning elections every two years than getting things done. Speaking almost evangelically about wonky-sounding reforms such as “biannual budgets,” “single-subject legislation,” automatic-spending sunset provisions, better fiscal oversight, and other “systemic” changes, he also boasts he has the “will,” “spine,” and “backbone” for the job.

During the 14 months working for Whitfield, Fareed, along with other Congressional staffers, flew to Turkey for a 10-day “educational” tour sponsored by a pro-Turkey lobby group. (Whitfield is a cofounder of the Congressional Caucus on Turkey and Turkish Americans, which is opposed to Congress formally recognizing as genocide the Ottoman government’s slaughter of 1.5 million Armenians around the end of World War I.) Fareed also worked on a Whitfield bill to protect Tennessee walking horses from cruel training methods. Whitfield’s wife, then a paid lobbyist for the Humane Society, used her husband’s congressional offices and staff to meet with as many as 100 other congressional members to promote the bill. The House ethics panel later rebuked Whitfield for this. He claimed he did not know at the time his wife was a Humane Society lobbyist — even though his staff did. He resigned this September. Ultimately the bill did not pass.

When Fareed quit in 2013, he moved back to Santa Barbara and worked, he said, for the family company. A year later he announced his candidacy for Congress, running against Republican stalwarts Chris Mitchum and Dale Francisco in the primary, to challenge 10-term Democratic incumbent Lois Capps. Republican party veterans strongly urged him to wait his turn and run for other offices. He refused. What Fareed offered in lieu of experience was energy and money. He gave his campaign $200,000. It helped. In the 2014 primary, Fareed came in just 600 votes behind Mitchum and 5,000 votes ahead of Francisco. He was 26 years old.

RACE IS ON:

When Lois Capps announced in 2015 she would not seek another term, both Carbajal and Fareed’s engines were revving. Carbajal had been painstakingly positioning himself to succeed Capps for some time. To get to November, however, Carbajal would have to run against popular Santa Barbara Mayor Helene Schneider in the June primary. Capps famously endorsed Carbajal in that primary, bringing the party establishment to Carbajal’s side.

Fareed, likewise, wasted no time making his intentions known. To make November, Fareed would have to beat Katcho Achadjian, a popular and well-respected assemblymember from San Luis Obispo who had supported Fareed in 2014.

In the 12 years Carbajal has been a supervisor — winning election three times — he’s never run a contested race against a viable opponent. As supervisor, Carbajal was accessible, likable, and indefatigable. If he found himself sideways with liberal supervisors such as Janet Wolf, he’d figure out how to patch things up. Carbajal always made a point to get along with 5th District supervisors, first Joe Centeno and now Steve Lavagnino — traditionally seen as adversarial to the South Coast environmental agenda. Without Centeno’s support, for example, Carbajal never could have secured the votes for his signature accomplishment, the children’s health insurance initiative that reduced the number of uninsured minors from 16,000 to 1,500. (Republican Centeno, incidentally, is supporting Fareed.) The second time Carbajal ran, Montecito moneyed interests went searching for a candidate to run against him. They couldn’t find a soul. Ultimately, they opted to support Carbajal. The third time Carbajal ran, his opponent left town halfway into the race.

Carbajal has run largely unopposed, in part because of his prodigious fundraising prowess. No one is more relentless. One developer confided Carbajal called him 10 times in one week. In the Democratic primary, Carbajal outspent Schneider by nearly two to one, secured almost all the pertinent endorsements, and fielded more precinct walkers and get-out-the-vote telephone callers. It wasn’t even close.

MONEY MATTERS:

Fareed’s access to campaign cash has set him apart, as well. It was the $200,000 he donated to his campaign in 2014 that brought him within striking distance of Mitchum. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee has since questioned how Fareed could give himself more than he actually earned and whether Fareed fully complied with campaign finance disclosure law. But it was in the 2016 primary that Fareed’s ability to raise large quantities of campaign cash raised eyebrows. The money came from donors who owned skilled nursing-home facilities outside the district. He has since argued that he had to go around the party establishment to wage a viable campaign against an entrenched insider like Achadjian.

Fareed has also come under fire because of the money, more than $100,000, that the oil industry has given to his campaign. The former CEO of Greka Oil and his wife have each donated $2,700. Greka is currently under legal prosecution by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for violations at their Santa Maria facilities where 500,000 gallons of oil leaked. Fareed’s campaign stated he only knew the former oil CEO as the owner of a boutique winery. Greka is currently seeking to depose Carbajal as part of the EPA case to determine if Carbajal exerted improper political influence in the EPA’s decision to sue.

Wherever the money came from — and however it arrived — it proved enough to retain big-name political talent like Rick Wiley — former campaign consultant for Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s presidential campaign — and Fred Davis, now legendary for his offbeat, creative political commercials. Achadjian ran a listless race and never counterpunched when attacked by Carbajal or Fareed. On election night in June, Fareed won a major-upset victory.

ALL-IMPORTANT VOTE:

With one week left before Election Day, Carbajal would appear blessed with statistical advantages. The Democratic voter registration, districtwide, has widened to 8 percent since June, when it was 6.4 percent. At that time, 10,000 more Democrats cast ballots in the congressional race than did Republicans. Schneider, his primary opponent, has endorsed him, though with little fanfare, and the party has unified. By contrast, Achadjian has declined to endorse anyone, and the South Coast Republican machine — to the extent one exists — is in unhappy disarray.

Democratic voter-registration drives have borne fruit in vote-rich Isla Vista, where student voters are expected to turn out in large numbers to defeat Trump and get pot legalized. Carbajal hurt himself with Lompoc voters after he was overheard jokingly suggesting that the city was the armpit of the county, and Fareed continues to pummel him in TV commercials. But Carbajal has raised enough money to fight back on the airwaves, and he enjoys the biggest advantage in numbers of volunteers.

As of October 19, Carbajal had raised $2.8 million for both the primary and general elections, and political action committees supporting Carbajal have raised roughly $2 million. Fareed’s campaign has raised $2.1 million, and PACs supporting him have reported raising $1.8 million. In the last quarter, Fareed out-raised Carbajal $730,000 to $600,000.

Statewide, the Trump factor appears to have hurt Republican candidates, and early voter turnout indicates 1.5 percent fewer Republicans have mailed in their ballots than they did this time four years ago. Conversely, some down-ticket Republicans are receiving more money than usual from donors disinclined to support Trump.

As of this writing, 101,528 voters have mailed in their ballots for the 24th District race, with Democrats ahead by 7 percent. After the same number of days in 2012, the number of ballots cast was 90,805. Republicans at that time enjoyed a one percent edge.

On the Issues

Here’s how Carbajal and Fareed break down.

ABORTION: Carbajal described himself as “100 percent pro-choice,” cites his “Giraffe” award from Planned Parenthood for sticking his neck out, and supports funding for Planned Parenthood. Fareed describes abortion as “an intensely personal decision,” says government should have no role, and has supported an investigation into Planned Parenthood in the past.

MINIMUM-WAGE INCREASE TO $15: Carbajal supports. Fareed opposes.

AFFORDABLE CARE ACT: Carbajal says it needs to be tweaked to address rising premiums. Fareed says it should be repealed but replaced with something that also protects those with pre-existing conditions.

OFFSHORE OIL AND FRACKING: Carbajal says he opposes both. Fareed says he supports a “decarbonized future” and describes oil development and fracking as part of the transition to get there. Both agree climate change is real. Carbajal says human activity is responsible. Fareed says it’s a contributing cause.

GUN SAFETY: Carbajal supports denying gun sales to anyone on the No-Fly List, background checks for ammunition sales, plugging loopholes to universal background checks, and holding gun manufacturers civilly liable for damage caused by their product. Fareed objects to lack of due process for those placed on the No-Fly List, says existing laws should be better enforced before new ones are passed, and stresses mental-health care in keeping guns out of the wrong hands.

TAXES: Carbajal calls for plugging tax loopholes and increasing taxes for corporations and the wealthy. Fareed supports a new flat tax and greater congressional oversight of the funds Congress spends.

HIGHER EDUCATION: Carbajal supports free tuition for community college students. Fareed calls for the creation of tax-exempt family savings plans earmarked for higher education.