Tom Hayden was a friend of ours. By “ours” I mean of me and my husband, Dick Flacks. He was also a friend of this community’s. I would like to take a page from MSNBC’s Chris Matthews, who ends his daily show by inviting his three final guests to “Tell me something I don’t know …” As the front-page obituary in the Los Angeles Times attests, Tom was a “famous person” — and not just because he married Jane Fonda. Herewith are some things you may not know about Tom:

He grew up — and was an altar boy — in the parish of Detroit’s notorious anti-Semitic priest Father Coughlin.

His middle name was Emmett, and he later wrote a book about the Irish Famine and Ireland’s continuing struggle for freedom.

He said that it wasn’t until he entered Royal Oak High School that he met any Jews.

He went to the University of Michigan on an athletic scholarship; he was the most fiercely competitive tennis player I’ve ever seen.

He was, in both his junior and senior years at UM, editor of the Michigan Daily, the campus and community newspaper. He investigated the Dean of Women and found that she would notify parents of girls who were seen dating black students and chastise the girls. She was soon fired.

He went as a reporter on a trip through the South in 1960, where he was severely beaten at a bus station in Mississippi, an experience that had a profound emotional effect on him, helping him become a radical.

He wrote, in 1962, the draft of the Port Huron Statement, the founding document of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the New Left, and of the student and anti-Vietnam War movements of the ’60s. It is still in print and is available online. It is a beautiful and seminal document. There were many academic conferences about it in its 50th anniversary year of 2012, including at UCSB and at the U of Michigan.

He worked with other SDSers in the ghetto of Newark, New Jersey, just before it exploded in 1967.

He served as one of the honor guards on the train that carried Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s body from L.A. to Washington.

He was part of the Chicago Seven, charged with “crossing state lines to incite a riot” — a charge a judge later dismissed on appeal from a raucous, unconventional trial. (A friend, observing that the Seven had been accused of “conspiring” to do dastardly deeds, remarked of the disparate group: “They couldn’t even conspire to order lunch!”)

He was married and divorced by age 23 and subsequently married Jane Fonda, with whom he had a child — the actor Troy Garity. (Tom and Jane did not want Troy burdened with either the Fonda or Hayden surname, so they bestowed Tom’s mother’s maiden name on Troy.)

He moved to California and, eventually, he and Jane purchased a “ranch” in the Santa Ynez Mountains and founded Laurel Springs Camp for both underprivileged children and the children of activists.

He ran, in 1976, in the Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate against incumbent John Tunney. He lost the election, but he carried Santa Barbara County. Tom was at the election-night party, which was at Harry’s restaurant.

He lived in Santa Monica and served the people there as an assemblymember and state senator, reelected numerous times, for the maximum 14 years. He was chair of the Senate Committee on Higher Education.

He attended our sons’ (secular) bar mitzvas and many family celebrations; we attended his last two weddings and have remained good friends with all of his wives — as did he.

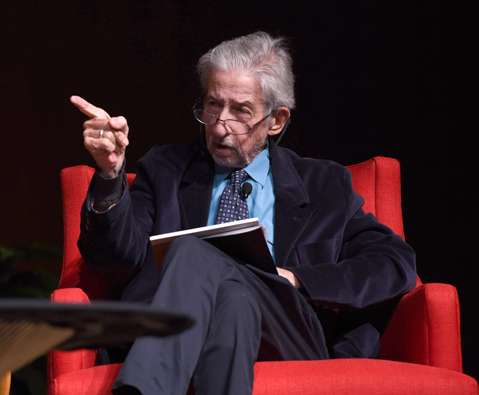

As a young man, he was one of the most exciting — though not bombastic — speakers Dick and I have ever heard. Almost every time he spoke, I felt I learned something.

He had great emotional depth — and could express almost none of it. As a young man, he came to our house in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for dinner, bringing a book that he read as we prepared dinner. At that time, he had strict Midwestern tastes, and I made meatloaf — the closest thing to hamburgers. I told him at the time that reading at a dinner party was rude, which surprised him. He read voraciously and constantly.

He wrote many books and was working on his final book about the anti-Vietnam War movement until his last days. It will be published posthumously, titled Hell, No!

President Franklin Roosevelt was said to love the following song, written for casualties of the Spanish Civil War. Tom was not exactly a casualty, but he was our comrade:

To you, beloved comrade,

We make this solemn vow,

The fight will go on,

The fight will still go on.

Rest here in the earth,

Your work is done.

You’ll find new birth

When we have won.

Sleep well, beloved comrade

Our work will just begin,

The fight will go on

Until we win.