When the U.S. Imprisoned Japanese Immigrants

A Remembrance of the World War II Detention Camps

“I heard they used my uniform for the exhibit,” said 89-year-old Santa Maria resident Tetsuo Furukawa, referring to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History’s new show — Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and WWII — which opened on Friday. It marks the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, ten weeks after the Japanese Empire attacked Pearl Harbor. The order emptied the West Coast of its residents of Japanese heritage.

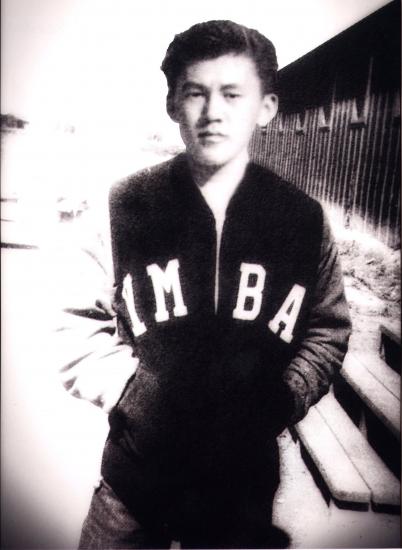

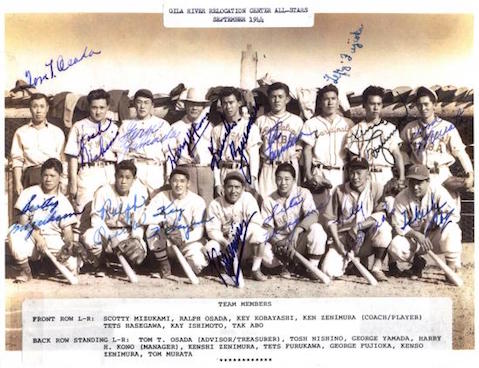

“It was 1945, April 18th,” said Furukawa, whose nickname is “Tets.” And it is baseball that he’s talking about, not the ferocious battles being waged on Pacific and European battlefields that year. Deported to the Gila River Relocation Camp in Arizona from his home in Guadalupe, Furukawa pitched for the camp’s high school team. The game that day was against the Tucson High School Badgers, state champions for the past three years with a 52-win, no-loss record. “Their pitcher, Lowell Bailey, had an earned run average of 0.00,” he said. “And we happened to beat them, 11-10, in 10 innings.” The rematch was cancelled because of the uproar in Tucson over being beaten “by the Japs.”

The Smithsonian show tells the story of the people sent to 10 U.S. prison camps — more than 110,000 of Japanese ancestry, about 74,000 of whom were U.S. citizens. Despite this treatment, nearly 18,000 Japanese Americans fought in the 442nd “Purple Heart” battalion, and about 6,000 more served with the Military Intelligence Service as translators, according to Densho, which preserves oral histories from that time. The camps were placed inland from the coasts, where authorities feared foreign agents were at work. Research in calmer times finds no Japanese Americans ever spied for Japan. The parallels to today’s proposed “Muslim registry” are clear.

How’d your team win over one like the Badgers? The Gila River Butte High School baseball team had a coach, Kenichi Zenimura. He’s the father of Japanese-American baseball.

What do you think of Donald Trump and the Muslim travel ban? This is a country of immigrants, just like the Japanese, Chinese, and the rest from the European countries. Most of them came from somewhere else. That’s how we’re all here. I would like to see it remain a country of immigrants.

As long as we don’t have terrorists and bad guys coming in with the good guys, I’m all for immigration. It does seem like Trump is having all kinds of trouble. I hope they can work it out and let the immigrants in. I’m all for that.

What happened when the 9066 order came down? I was 14 years old. Some of the prominent Japanese in Guadalupe, about seven were picked up by the FBI on the night of December 7. The issei parents [first-generation Japanese] from Santa Maria and Guadalupe, 98 or 99 percent of the fathers were rounded up on February 18, 1942.

On April 29, 1942, all the Japanese in Guadalupe were bused to the Tulare Assembly Center. We were forced into horse stables. We lived there for about four months while they built Gila River and Manzanar and the other camps. In August 1942, we were put on a train and left Tulare for Gila River. The camp was built on an Indian reservation.

Was your father able to join you? My father was first sent to a defunct CCC camp in Tujunga — for interrogation and to get processed. He was put on a train all the way to Fort Lincoln in North Dakota. Eventually he came to Gila.

They brought charges against all the Japanese. They had to, in order to hold them. Ridiculous charges. They were all hardworking farmers and shopkeepers. None of them were terrorists.

My father was a farmer. We lived in an old schoolhouse that became vacant in about 1934 on a 200-acre ranch. There was a 20-foot light post in the front and the back, and every time any of us five boys or two parents went to the front or back — the outhouse was about 100 feet away — we’d turn the lights on and off at night. The Japanese shower and bath were detached, too. With seven people in the house, you can imagine how many times the light went on and off.

They accused my father of sending messages to the submarine off the Guadalupe coast.

There was a submarine off Guadalupe? Yes. From our house to the Pacific is about 10-12 miles, sand dunes and all the rest. It’s just about impossible to send a Morse code message with the light post. But they had ridiculous charges, all kinds of false charges, to hold people.

How did your family come to farm 200 acres? The parents couldn’t apply for citizenship. Without citizenship, you couldn’t buy property. Because of the 442nd, in 1952, the McCarran-Walter Act gave Japanese the chance to apply for citizenship. Japanese were not allowed to marry outside their race either — some did.

My father leased the land from owners who were Swiss. A good friend had a son in his thirties, a nissei [second-generation Japanese American]. My father used his name to lease the ranch. My eldest brother was 19 or 20, and my father had been waiting for him to turn 21 so he could lease the land. But that didn’t happen. Pearl Harbor interrupted us.

A friend of mine made a thousand cranes, and I sent it to the Smithsonian for the display. And I wrote a haiku:

Nine zero six six

Humiliation, locked up

Day of infamy

I wrote it because everything in there pertains to me. I lived through all this.