Mister Rogers Documentary Is Fluid Blend of Biography and Cultural History

‘Won’t You Be My Neighbor?’ Incites Viewers to Reflect on the Integrity and Vulnerability of Childhood

One of the most resonant moments in Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, a film that reverberates with poignancy, is when Mister — Fred — Rogers avows that the relationship between a television viewer and what they encounter on-screen is sacred. He was speaking as an ordained minister in the heyday of mass media, the ’60s, when the word “broadcasting” meant something more narrow than it would in short time. Children who turned on the TV at a particular hour were more or less a captive audience, with few other options for audiovisual stimulation. So, Rogers wondered, didn’t adults bear a responsibility to do right by them — to offer something more substantial than crude entertainment? Didn’t television offer an unparalleled opportunity to speak to the greatest mystery that faced them — their own feelings?

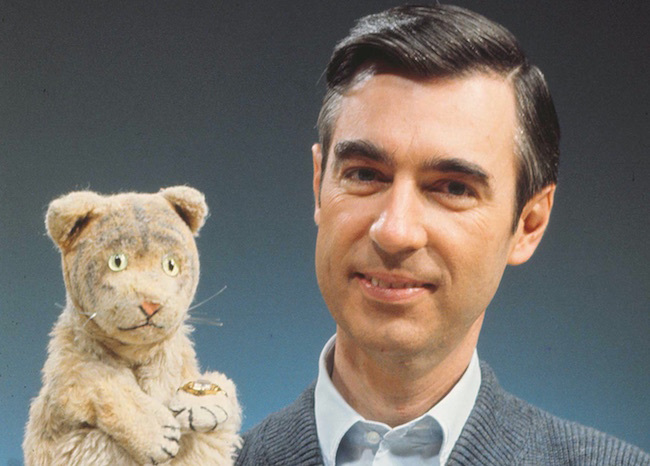

Debates about media’s influence on and duty toward children have played out again and again in the ensuing decades. Arguably, though, no contemporary American media personality has attended to the special needs of children with the singular respect, tenderness, and tenacity that Rogers, who died in 2003, did in the three-odd decades that Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood aired on PBS. Rogers’s approach to TV was also singular in a literal sense: As he explains in the film, he spoke on camera as though he were addressing only one person. Director Morgan Neville and his team capture the potency of this voice in their remarkable picture of Rogers’s work. Drawing on touchstones from Rogers’s series, behind-the-scenes footage, and recent interviews with his family, friends, and collaborators, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? forms a fluid blend of biography and cultural history.

The film’s sentimental mood keys in to current concerns. Incidentally released as state-enforced family separation at the U.S. border severed young children from their parents, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? incites viewers to reflect on the integrity and vulnerability of childhood. How a society treats children — all of them, regardless of family or ethnic origin — is a hallmark of its overall moral and ethical orientation. Neville’s film reminds us that Fred Rogers would no doubt have crumbled at the notion that some children’s well-being must be sacrificed for the future of others’. And in its measured portrait of Rogers’s philosophy, it nudges us toward a framework for thinking otherwise.