Brave New Virtual World at Santa Barbara City Hall

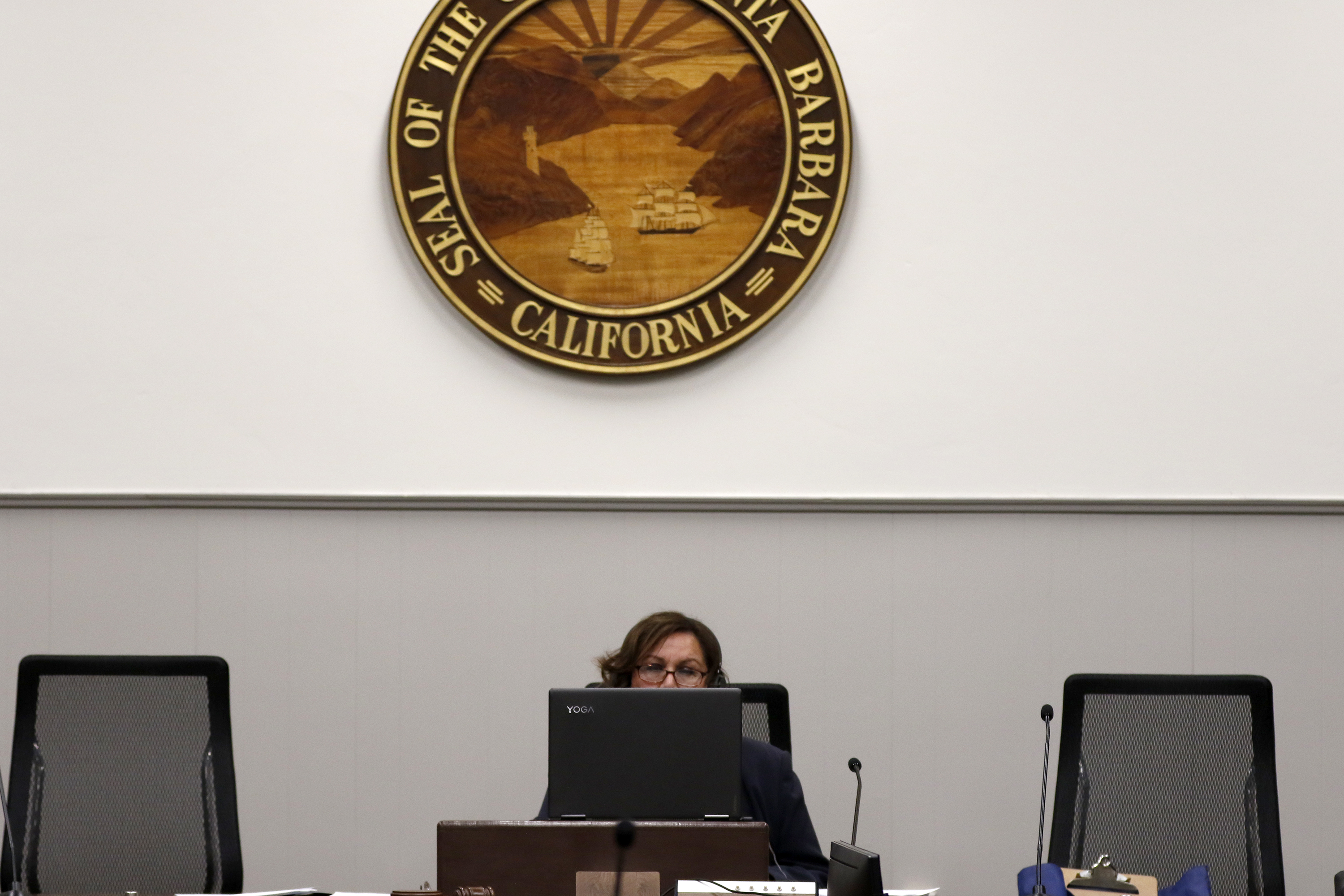

Mayor Murillo Has House to Herself

When it comes to high-profile displays of social distancing, this week’s most dramatic — not to mention most surreal — public flex goes to Santa Barbara Mayor Cathy Murillo. During Tuesday’s City Council meeting, Murillo had the dais entirely, completely, and exclusively to herself. “It was tiring,” Murillo would comment afterward. “We forgot to factor in time to take a break. So, I had to sit there for five hours straight,” she said. “It was intense. Normally at council meetings you don’t have to worry about looking at the camera. I had to remind myself not to look down.”

In sharp contrast, the Board of Supervisors meeting — held the same day but a few blocks away — was positively a mob scene. Three of the five supervisors spread out on the dais in the Santa Barbara supervisors’ chambers on the fourth floor of the downtown County Administration Building, and the remaining two beamed themselves in remotely from the county’s Santa Maria meeting room. Supervisor Das Williams distinguished himself by wearing a face covering during the meeting, though mostly around his neck. (He also brought his oldest daughter along, though her patience with board deliberations soon wore thin, and she quickly absented herself from command and control.)

Murillo may have been the only elected official on the dais — or in the room for that matter — but she was not alone. All six councilmembers joined in remotely from either their homes or their offices, thanks to the technological magic of GoToWebinar. As with all efforts to embrace new technologies, there were bugs to be worked out. For this week’s council meeting, no fewer than three rehearsals were required. Also chiming in were City Manager Paul Casey and City Attorney Ariel Calonne, each from their respective City Hall offices offscreen, as well. Had they stayed in the chambers, the feedback from their microphones could have rendered the meeting’s acoustics excruciating to those attempting to tune in. Members of the public were given a venue for weighing in, as well, though only their voices were transmitted.

Murillo all but had the council chambers — with a capacity of 165 — completely to herself. City Clerk and elections czar Sarah Gorman was on hand to make sure the trains ran on time and all the circuits were connected. Officer Craig Burleigh of the Santa Barbara Police Department sat in a pew in the back of the chambers just in case anyone got rowdy.

No one got rowdy.

No one was there.

Only Noozhawk reporter Josh Molina showed up, but just long enough to take a few cell-phone snaps and split. Burleigh, who wore a mask for about half the meeting, had no order to maintain.

Welcome to the outer limits of virtual government. And no, your TV sets cannot be adjusted in the meantime, at least not until the coronavirus has run its course. No one knows when that will be.

The main topic of discussion — the only one really — was the virus. “I’m a little paranoid,” the mayor conceded. “I really don’t want to get it.” She said she’s taking precautions. “I work,” she said, “but I make a point to take naps, too.”

Debuts and Disasters

Murillo’s political career has been weirdly punctuated by horrific disasters. The day she was sworn in as mayor was the day the debris flow wiped out Montecito, killing 23. Late last summer, the Conception was engulfed in nighttime fire, killing 34 passengers and crew, the day Murillo was poised to announce her bid for statewide office. By the time the election results were in and Murillo discovered she’d come in third in a two-way race, the coronavirus had just established itself as a massive global threat. “What happened to the good old days when Queen Elizabeth came to visit?” she asked. But as usual, the good old days were never that great. When the queen showed up back in early 1983, pounding rains had just scoured out the city’s waterfront and left much of the South Coast wetter than a drowned dog.

Technically, legally, and politically, the pandemic is a matter of county jurisdiction, a crisis for the county’s Public Health Department — now buttressed by the county’s emergency response infrastructure and the incident command throw-weight offered by the county’s public safety chieftains, old pros now in the art and science of massive community fire drills. Dr. Henning Ansorg, the county’s public health officer, holds the unique authority to declare a quarantine.

Ansorg, at the helm now for only a year, is frequently one of the key public faces for the response. To date, no one has emerged as Santa Barbara’s equivalent to Andrew Cuomo for the disaster, or Gavin Newsom for that matter. To the extent anyone has — if only sort of — it would be County Supervisor Gregg Hart, who just assumed the role as board chair. Hart — a lifelong political animal with an easy command of detailed bureaucratic intricacies — has taken it upon himself to make sure that the county’s public health experts — with no expertise in the rigors of political messaging — do a much better job than they otherwise would in communicating with the public and the media.

The efforts, to say the least, are very much a work in progress. For the time being, Hart is attempting to get the best information out while at the same time minimizing news that might lead the public to panic, despair, or despondency. For him, the only message that matters right now is that of social distancing; everything else is extraneous and needs to wait until after we’ve flattened the proverbial curve.

What role the mayor can play in all this is a matter of ongoing discussion, but certainly Murillo has at her disposal the amorphous bully pulpit her office affords. With a population in excess of 90,000, what happens in the City of Santa Barbara has a big impact on what happens in the county. And vice versa. In this context, critics of the mayor have begun to wonder with more than a little impatience, “Where’s Cathy?” Whether this is motivating Murillo or not, the mayor is now trying to carve out more of a public role. She’s produced a handful of short videos — she made one with Councilmember Meagan Harmon on the art of making face coverings, for example — and another on the importance of supporting local businesses.

Murillo, a theater arts major at UCSB and a former reporter (with the Santa Barbara Independent), is still finding her way. Even short videos, she’s discovering, take much longer to put together than expected. And by the time her productions are ready to post on social media, Murillo noted, the information they contain is already obsolete. “It’s good for maybe 10 minutes, max,” she said. “After that, it’s already old.”

What a Difference the Weeks Make

Leading off Tuesday’s deliberations was City Administrator Paul Casey, who until six weeks ago only had to worry what downtown property owners — angry about empty storefronts, what they term the bureaucratic indifference of City Hall, and what they contend is the bloated pay of city bureaucrats — thought of him. In public meetings, Casey exudes a calming, congenial competence. On Tuesday, he provided a rundown of what City Hall had done so far in response to COVID-19 and what grim choices lay ahead.

To date, he noted, City Hall had shut down the municipal golf course, all bars and restaurants — except for takeout — basketball courts, the skateboard park, all public picnic areas and barbecue pits, and all parks from any active recreation—including and especially large-scale yoga classes. City Hall, Casey stressed, desperately wanted to keep parks and beaches open, but he needed the community’s best efforts at social distancing to make that possible.

Many Southern California municipalities have already closed off their beaches. Some social media critics have posted photos taken of beachgoers at local beaches — Hendry’s most conspicuously — manifesting an indifference to the constraints of social distancing. None are as flagrantly reckless as the spring break mobs caught on video a few weeks back in Florida, but the six-foot rule is clearly being ignored in smaller clusters. Yoga and exercise classes of 40 people in city parks, he said, cannot continue. Parks are now for walking through, not hanging out in.

“If you get to a destination,” he cautioned, “please don’t. Stay in your neighborhood.” For those not getting the message, he added rhetorically, “Is it hard? Yes, it is. It’s supposed to be.”

Oscar Shaves

Casey got a little pushback Tuesday evening from Councilmember Oscar Gutierrez, who represents the city’s Westside. Gutierrez objected to the closure of the waterfront’s boat launch. With so many people losing their jobs, Gutierrez argued, some people will need to fish just to feed their families. They can’t do that, he pointed out, if they can’t get their boats in the water.

Gutierrez was sporting a conspicuously clean-shaven look after having asked a couple weeks ago if beards — such as the one he then had — provided a welcoming environment to the coronavirus.

Casey, however, wasn’t budging. Santa Barbara’s public boat launch, he said, was the last one in Southern California to be shut down. He didn’t want Santa Barbara to become a mecca for leisure-craft operators. And phone calls had been coming in by the hundreds from out-of-town boaters looking for a place to launch. As a possible half-way gesture, Casey suggested, perhaps the boat launch could be re-opened during weekdays but not on weekends.

Casey also related how MTD was cutting back its bus lines in the wake of the virus. The State Street shuttle, which ferries tourists from the waterfront to downtown, has no visitors — or residents — to carry and ceased operations this week. The labor line, he acknowledged, had been the subject of more than a few calls of concern, with reports of 150 workers congregating on Yanonali Street by the wastewater treatment plant. Mayor Murillo asked, “Can we get some masks and take them down to the labor line?” Casey said he’d heard such an effort might already be in the works.

The meeting picked up steam as Laura Dubbels, the city planner charged with overseeing homeless response efforts, took to the virtual podium. Dubbels was there to explain what steps have been taken to get the most medically vulnerable homeless somehow under wraps as the coronavirus gathers destructive steam.

To date, South Coast authorities have worked long hours to accomplish a lot of little things. There is no new shelter yet, nor one likely to happen soon. Likewise, efforts to secure hotel and motel rooms for the homeless — as authorized by Governor Gavin Newsom in one of his many emergency edicts — have yet to bear fruit. But that’s not to say nothing has been accomplished.

Dubbels noted that the Showers of Blessing — a portable shower service targeting the homeless — is now operating three days a week in Santa Barbara parks. The Foodbank is conspiring with Home for Good and City Net — two nonprofits dedicated to homeless outreach — to provide much-needed meals since two parks-based nutrition programs have been shut down out of concern for the virus. Not mentioned, New Beginnings — a nonprofit providing supervised and curated parking spaces for 120 vehicle dwellers — has started an “Amazon registry” to enlist public donations for food items that do not need a microwave or other preparation devices that most homeless people are not likely to have: peanut butter, tuna fish, jerky, and the like.

Sheltering the Unsheltered

Initially the plan — or the hope — was to open emergency shelters in the county’s northern and southern regions. The Santa Maria emergency shelter opened three weeks ago and now provides space for 71 people a night. The problem was finding trained and experienced people capable of staffing what’s admittedly a challenging enterprise. Only this week has management of the shelter been taken over by such an operator, the Good Samaritan Shelter. Many of the volunteers who have traditionally helped provide shelter and other services to the homeless are older, a group notably at risk to the virus. Not surprisingly, the number of volunteers throughout the county has shrunk dramatically in recent weeks.

Finding a South Coast facility has proved challenging. The Carrillo Rec Gym was mentioned as a likely site, but only after school locations were nixed. Many homeless people in shelters smoke; smoking is not allowed on school campuses. It’s complicated. But without a willing operator — with experienced, trained staff — that’s not going to happen.

In the meantime, the Center for Disease Control — not to mention local health-care professionals — have argued that such concentrations of medically vulnerable people pose unacceptable risks. On this ground, Dubbels dismissed a suggestion brought up by Councilmember Harmon to allow homeless people to camp in city parking lots, so long as acceptable distances could be maintained. The thinking now, Dubbels explained, is to leave homeless encampments — always they are referred to as “encampments” but never merely “camps” — alone. Case managers working with the homeless, she explained, tend to know where to find their clients if and when their cell phones run out of charge. If they are rousted from their campgrounds, she concluded, they’ll be lost to their caseworkers. Should they get infected, that would be seriously problematic.

To date, one of the two people whose lives have been claimed by the COVID-19 virus in Santa Barbara was a homeless man, Leland Goodsell. He famously stayed away from homeless shelters. Dubbels told the councilmembers that no shelter dweller has yet tested positive for the virus.

Governor Newsom empowered cities and counties to commandeer local hotels and motels on an emergency basis to create emergency housing for the homeless. Seventy-five percent of the costs can be reimbursed by the Federal Emergency Management Administration, and 75 percent of the remainder can be reimbursed by the State of California. To date, the County of Santa Barbara has managed to secure only a handful of hotel or motel rooms for this purpose. Ventura County, by contrast, has secured 271 rooms split up throughout four motels located in three cities.

Homeless care advocates, impatient with the slow pace of progress, have cited Ventura’s success. Why hasn’t Santa Barbara kept pace? they’ve demanded.

Murillo, who once lived in Ventura, said there’s been no shortage of effort by city and county administrators charged with homeless care and outreach. Many in the hospitality industry, she explained, are worried about the downstream ramifications of being branded as a “Virus Hotel.” Ventura County, she noted, has twice as many people as Santa Barbara and many more single-room-occupancy hotels. Almost all of what once passed for fleabag hotels in Santa Barbara have since been converted to mainstream or upscale accommodations.

And Then There’s Lavs

One of the chronic sore-thumb issues attending the city’s response to the homeless population has been that of public restrooms. On one hand, people living on the streets need a place to go and a place where they can wash their hands. On the other hand, city parks and rec workers — not to mention parking lot workers — are familiar with the intense wear and tear some street people can inflict on public accommodations. Dubbels alluded to “a lot of abuse” of the city’s restrooms and “security issues.” She noted that City Hall has identified five public restrooms that could be kept open all day and all night for the homeless, but she’s still hammering out the cost-sharing details when it comes to security and hygiene with her counterparts with the County of Santa Barbara.

Councilmember Harmon asked what happens when homeless people think they may be infected; who should they contact to get tested? The answer was anything but clear. Dubbels suggested they should contact their physician, if they had one, or their medical provider at the county’s Public Health Department, both medical bureaucracies that are hard for anyone to navigate quickly. The problem is exacerbated by the lack of testing kits, lack of testing swabs, and the stinginess with which many medical professionals have found themselves forced to dole them out.

Homeless people given the test have been placed in local motel rooms pending their results. How many hotel rooms exactly is uncertain, but somewhere between 10 and 15. That doesn’t count the eight motel rooms that have been secured by a nonprofit to house homeless people undergoing cancer and other serious medical challenges not directly related to COVID-19.

‘A Little Crime Uptick’

Next up after Laura Dubbels was Police Chief Lori Luhnow, beaming to the councilmembers and their webinar site via the magic of the city’s webinar program. Luhnow acknowledged that seven law enforcement officers in the county have tested positive for coronavirus — not counting the prison guards at the Lompoc Penitentiary — one of whom is a city cop. He, or she, is still quarantining at home. Two other cops were suspected, but ultimately tested negative.

Luhnow didn’t discuss the shortage of protective clothing — gloves, masks, gowns, and goggles — but it’s a fact. A philanthropy dedicated to local law enforcement intervened to make sure cops had enough sani-wipes to wipe down the backseats of their cop cars. Many functions that used to be done face-to-face — like taking crime reports — are now taking place virtually or over the phone. The police station is technically open to the public, but only barely.

Immediately after the state of siege was declared, Luhnow reported, her department saw a 40 percent drop in calls for service. That’s leveled out since then, she said; now it’s about 10 percent less than normal. Although there are far fewer drivers on the road, there are more distracted drivers. And with the governor imposing a new no-bail rule on low-level offenses, Luhnow said, “We anticipate a little crime uptick.”

Like many in law enforcement, she expressed concern about a rise of domestic abuse because of sheltering in place. She urged people in the community to check in on friends, relatives, and acquaintances if they think that might be happening.

Luhnow also addressed outreach efforts undertaken by her department to reach out to Santa Barbara’s Spanish-speaking community. Two Spanish-speaking officers have been assigned to get the word out about social messaging. Radio Bronco, she said, has been a receptive venue, and her department is maximizing social media.

As far as people who are violating the social-distancing edicts imposed by the state, the county, and by the City Council itself, several members of the public highlighted the extent to which they believed this was happening. Luhnow was emphatic that the county’s limited 9-1-1 dispatch resources should not be consumed with such complaints.

Produce-Pinching at an End

Last on the agenda was a presentation by Sam Edelman, executive major domo of the Santa Barbara Certified Farmers’ Market. Although the number of people showing up at the farmers’ market has dropped dramatically — some estimates suggest by as much as 75 percent — Edelman said the show will go on. He outlined a host of measures designed to enhance social distancing. The farmers’ market is no longer a place where old friends and new friends can bump into each other and chew the fat while they poke, prod, and pinch the locally grown produce. The new operational mantra, Edelman said, is “Come, shop efficiently, and leave.”

Handwashing stations are posted throughout, no samples are given out, and shoppers are now funneled in at one major entrance, he said. This way, Edelman said, market organizers can meter the number of shoppers to no more than 150 at any one time. Organizers are now limiting the number of customers, he said, to two to a booth. Each booth is 22 feet long. Leafy greens must be pre-bagged.

In recent months, the farmers’ market has become the subject of some controversy at the council, mostly involving the city’s plans to move the market elsewhere so City Hall can build a new police station on the Saturday site. Many of the farmers have adamantly resisted many if not all of the relocation options, which has in turn generated some jaundice among certain councilmembers. Although the farmers’ market clearly falls within Governor Newsom’s list of exceptions to his emergency shutdown orders — grocery outlets are deemed essential — it is also the largest single group activity still allowed.

None of this tension was even hinted at this Tuesday. Councilmember Kristen Sneddon asked Edelman whether the market was thinking about curb-side pickups. He replied they had thought about it, but there were no plans to do it.

Money Gone, Money Waived

The last official word went to Administrator Casey, who notified the council in vague but emphatically grim terms the extent of economic violence the pandemic and the shutdown has inflicted on the city’s budget. “It’s going to be very significant,” he said, with an emphasis on the word “very” and even more on the word “significant.” Already City Hall has furloughed more than 500 hourly employees. To date, there have been no discussions with the unions representing city workers regarding pay cuts or furloughs — but given Casey’s expectation that the crisis will wipe out the $30 million City Hall has in reserves, it’s only a matter of time.

Casey explained that the $2.2 trillion federal bailout package has no sugar for cities with populations less than 500,000. Maybe the state would help out, Casey said, but by his manner he made clear he wasn’t expecting much.

Ironically, the fiscal nightmare looming for local governments might well delay any move on the horizon for the farmers’ market. Revenues generated by the special sales tax just approved by city voters to cover the costs of the new police station and other long-festering infrastructure improvement could well find themselves cannibalized to cover the costs of more immediate needs. Although the bond measure approved by voters was only to cover the cost of these infrastructure needs, it did not preclude other uses. As one City Hall insider put it, “If this isn’t a major emergency, I don’t know what is.”

That being said, the council voted to waive about $350,000 in parking fees owed by downtown businesses for two months and to defer for three months the bed taxes that would have been paid by hotel and motel owners.

In the meantime, Mayor Murillo has followed up on reports of beachgoers recreating too closely to one another, engaging in some recon efforts in her car by Leadbetter Beach. “I’m looking at some people who aren’t wearing masks. I know some people just don’t get it,” she said. “But mostly, I think we’re doing a pretty good job.”

At the Santa Barbara Independent, our staff continues to cover every aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic. Support the important work we do by making a

You must be logged in to post a comment.