A History of Stearns Wharf,

S.B.’s Doorstep to the World

John Peck Stearns Transformed a

Sleepy Adobe Town into a Bustling American City

By Tyler Hayden | October 6, 2022

Read all of the stories in our “Celebrating 150 Years of Stearns Wharf” cover here.

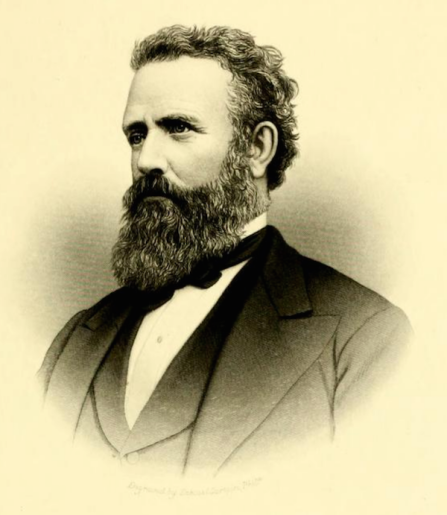

When John Peck Stearns, an East Coast transplant, proposed building a wharf in Santa Barbara, “people generally made it a fashion to regard him as a dreamer and a fool,” a journalist wrote at the time. “It was the theory, widely held, that a wharf would not stand up under the assaults of waves and wind, and that the man who would put his money into it was simply sinking it into the sea.”

But Stearns would not be deterred, and in 1872, using redwood from Santa Cruz, a crew out of Hueneme, and a loan from Col. W.W. Hollister, he built the structure that brought vibrant commerce and throngs of visitors to Santa Barbara and transformed it from a sleepy adobe town to a bustling American city.

Stearns was born in 1828, a member of one of the oldest lineages in Massachusetts, who traced their roots to 1630 English immigrants. Large families seemed to run in the Stearns households — his father was the 23rd child in his family, and Stearns was the 11th in his own.

At age 22, like so many young men back then, Stearns headed west, first settling in Illinois before pulling up stakes and moving to California during the Gold Rush. But unlike his contemporaries, Stearns ignored the lure of precious metal and became a teacher while taking up the study of law. After passing the bar, he was elected to two terms as District Attorney for Santa Cruz County and, toward the end of the Civil War in the 1860s, was appointed an assistant assessor by the federal government.

In 1867, for reasons unclear, Stearns forsook his budding career and relocated with his wife, Martha, to Santa Barbara to open the county’s first lumber yard, situated on the southwest corner of State and Haley streets. Perhaps he heard the region was ripe for settling, and that it was experiencing an early building boon. The city’s population at the time was around 1,500, with about 500 American residents and the rest of Spanish, Mexican, and Chumash descent.

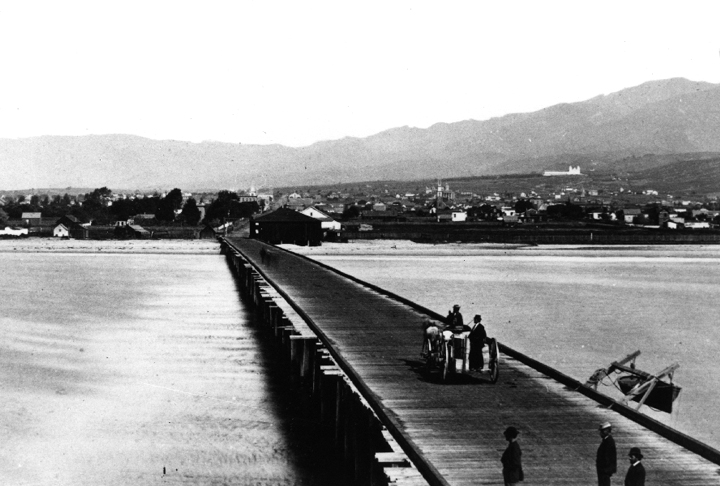

Though his business venture quickly proved successful, something irked Stearns. The 500-foot Chapala Street Wharf, which had recently opened, was too short for large ships to tie up, and big pieces of cargo — like lumber — were simply thrown overboard and floated with lines to shore. The process was lengthy, laborious, and often damaged the wood. Stearns also didn’t appreciate paying lighterage fees. Passengers, too, had difficulty making land. They had to be rowed to shore, and depending on the weather and skill of the ferriers, sometimes ended up in the drink.

Stearns initially tried to persuade the Chapala operators to extend their wharf, even offering to pay for the work, but he was rebuffed. So he took matters into his own hands and approached Hollister, Santa Barbara’s leading philanthropist and businessman, “who had great faith in Mr. Stearns’s vision and judgment,” a reporter from the era stated.

Hollister loaned Stearns $41,000 to build a 1,600-foot wharf with an agreed payment schedule of $500 a month for seven years. Despite major storms, heavy damage from one of Santa Barbara’s only recorded tornadoes, and other disasters — like when a Chinese junk in rough seas crashed through the wharf, tearing nearly half of it away — he never missed a payment. He also cut freight weights in half.

“Of course the wharf was a success and made money from the start,” another historical account says. It put the Chapala Street Wharf out of business, “and then a queer trait of human nature manifested itself — the people who had been calling Stearns a fool began showing their envy and jealousy because of his success. It became the fashion to knock him as hard as it had been to poke fun at his plans.”

The ill will culminated in the Board of Supervisors slapping a $50 monthly fee on the wharf. Stearns was outraged. “I’ll never pay it!” he famously declared. When another storm ripped away dozens of pilings and rendered the wharf inoperable, Stearns refused to make the repairs until the fee was rescinded. Feeling pressure from panicked merchants and city officials, the supervisors eventually buckled.

The lumber that flowed into Santa Barbara would soon replace adobe and brick as Santa Barbara’s building material of choice. When the train arrived, Stearns built a rail wyre where the Sea Center now stands so freight could be loaded and unloaded from schooners directly onto flatcars without skipping a beat.

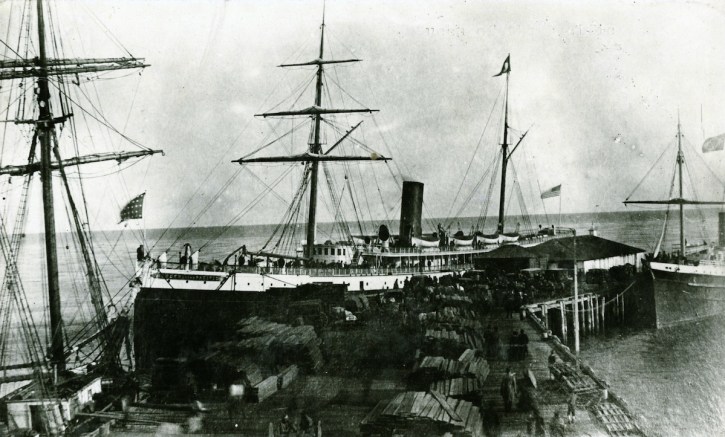

But it was hardly just goods and materials that Stearns Wharf brought to the city. It also brought people. Droves of them. Before it was built, and before the train tracks were laid, the only practical way in and out of the region was by stagecoach, a long and dusty journey. Large coastal steamers could now park right at Santa Barbara’s doorstep, which they did on an almost daily basis.

A well-read book published in 1872 — California for Health, Pleasure and Residence: A Book for Travellers and Settlers by Charles Nordhoff — was also a major windfall for the city. “Santa Barbara is on many accounts the pleasantest of all the places I have named; and it has an advantage in this, that one may there choose his climate within a distance of three or four miles of the town,” Nordhoff wrote. “It has a very peculiar situation…. Santa Barbara faces directly south … with the sea and lovely islands in front of it and a range of mountains to the north…. Santa Barbara temperature is not extreme.”

The wharf was by no means Stearns’s only venture. Along with Hollister, he helped found Santa Barbara College. He was very active in the Congregational Church, Masonic order, and Republican Party, becoming a delegate to the national convention. In 1888, he was elected mayor of Santa Barbara. Among the reforms he pushed through was putting the city’s first uniformed police on the streets. Stearns also got heavily involved in journalism. He became owner of the Santa Barbara Press when its owner was shot to death by an enraged reader.

Stearns retired as president of the Stearns Wharf Company in 1898, after which he moved to Sonora to be near his daughter. He died there in 1902 at the age of 74 but was buried in his adopted hometown at the Santa Barbara Cemetery.

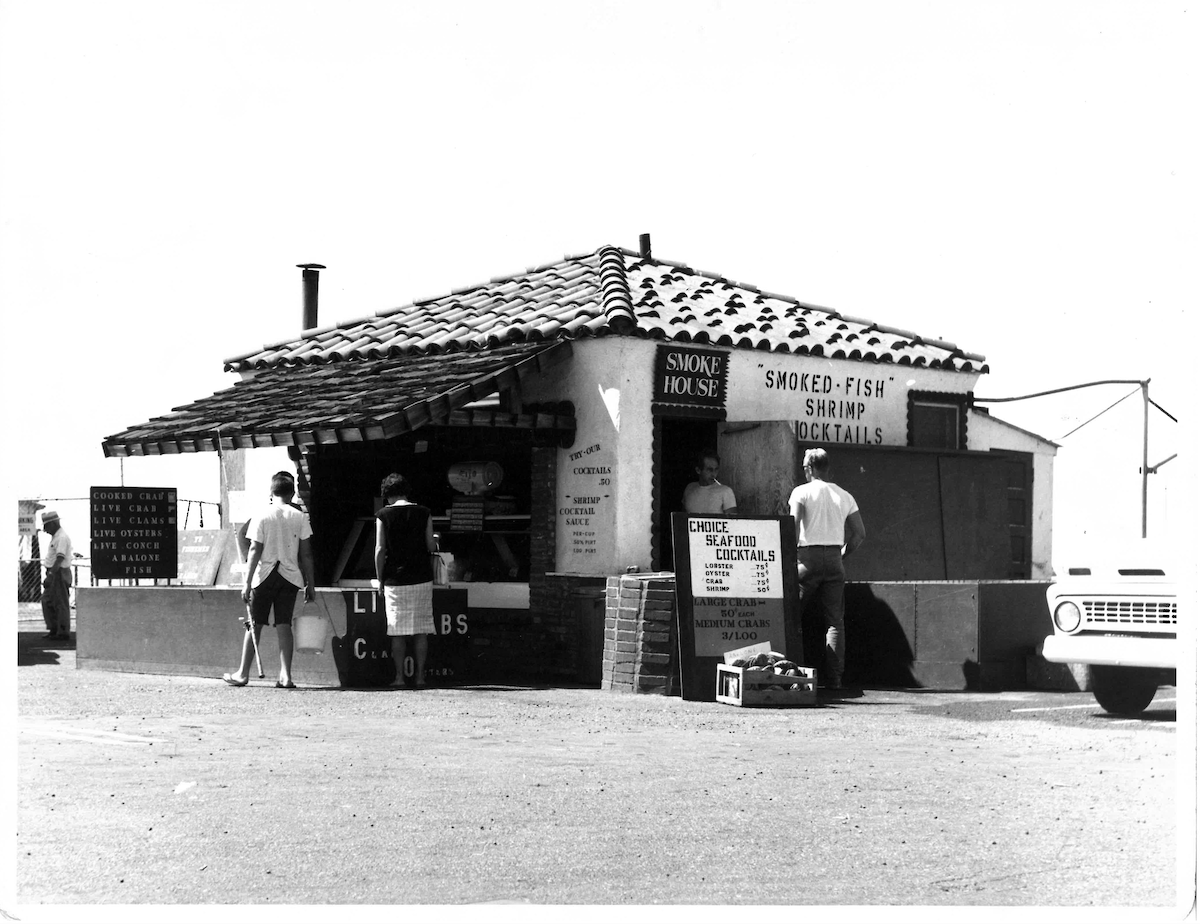

Of course, the wharf continued on, slowly evolving from a site of heavy industry to one of tourism and leisure. It closed to the public for a time during World War II, and in 1944, a Hollywood syndicate including actor James Cagney bought the property for around $200,000. That era was short-lived, however, when the group discovered necessary repairs would cost more than the purchase price and would require more than 10 million board-feet of lumber.

Santa Barbara furniture dealer Leo Saunders then purchased the wharf franchise, which by that point had grown to include two restaurants and a yacht club. Saunders frequently clashed with the city over sewer discharge that polluted nearby beaches, and in 1955, he relinquished control to a new group of buyers that included fishing magnate George Castagnola.

Then, the oil industry arrived. But the 1969 spill, and a later fire that destroyed the Harbor Restaurant, conspired to close the wharf for nearly a decade. It reopened in 1981 under the auspices of the City of Santa Barbara, which runs it to this day.

More than a million people now visit Stearns’s legacy every year, one of the oldest working wooden wharfs in California. And though its days as a shipping hub are over, memories of that era endure.

“There is a fascination about the ships that never palls,” resident and Stearns Wharf stockholder Frank Smith said in 1922. “I like to be around the wharf and see the lumber schooners come in and unload and go on their way again. The wharf has been a very large part of my life, and it is a good deal like home to me.”

Special thanks to Neal Graffy, Michael Redmond, the Santa Barbara Historical Museum, and the City of Santa Barbara’s Waterfront Department for their contributions to this article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.