This article was originally published in UCSB’s ‘The Current‘.

Rivers carry plastic across continents, so scientists tracked its movement across continents too.

A sweeping new UC Santa Barbara-led study spanning four continents and eight countries has amassed one of the largest datasets ever collected on plastic pollution in rivers — offering insights that the researchers responsible believe are key to helping turn off the tap of plastic waste.

Between 2020 and 2023, researchers worked with local partners to collect data from river sites in Mexico, Jamaica, Panama, Ecuador, Kenya, Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia. But the study, published in the Journal of Environmental Management, was much more than data gathering.

“What’s really exciting about this effort is that we were able to answer the same question — what does plastic pollution actually look like in rivers — across many different contexts, geographies and cultures,” said lead author Chase Brewster, a project scientist in UCSB’s Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory.

Unique among many global pollution studies, the project took a community-led approach that emphasized local autonomy. Local nonprofits and social enterprises led the work in their own communities, sorting plastic waste by item type and polymer category over three years. “Each site was an independent project,” Brewster explained. “They weren’t just collecting data. They were implementing technology to remove plastic from rivers, engaging governments, empowering communities and improving local conditions.”

Together, these local teams form the Clean Currents Coalition, a global initiative directed by the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory to intercept plastic before it reaches the ocean while fostering education, local engagement and systemic change.

Over the three-year period, teams collectively removed and analyzed 3.8 million kilograms of river debris (equivalent to 380,000,000 single-use plastic water bottles), with 66% classified as macroplastic. This large-scale, synchronous effort — rare in its scope and level of coordination — enabled researchers to compare data across diverse social, economic and environmental settings.

Researchers found substantial variation in the amount of plastic pollution intercepted in rivers studied — but all had plastic. Scaling up average plastic collection rates documented in this study would generate a preliminary estimate of 1.95 million metric tonnes (Mt) of plastic traveling down rivers worldwide every year. “That is an immense amount of plastic pollution,” said co-author and Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory Director, Professor Douglas McCauley.

“There’s been a lot of modeling about how much plastic is moving from land to ocean, but we didn’t have good on-the-ground data about what kinds of plastic are showing up, or why,” Brewster said. “This project actually let us see those differences and test ideas about what policies and systems are working.”

“In a moment when the growing number of headlines about the threat of plastic pollution to human, animal and planetary health may cause us to throw our hands up in dismay, this work shows that river by river, community by community, we can gather data needed to inform lasting, systemic change and inspire hope along the way,” said Molly Morse, director of the Clean Currents Coalition and senior manager of the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory.

For instance, the study found evidence that plastic bag bans can reduce leakage. “In Vietnam, where there’s no plastic bag ban, the proportion of bags in river waste was much higher than in Kenya, which has a full ban,” Brewster said. “It’s not a silver bullet — how you design and enforce these policies matters — but it shows they can work.” The planned implementation of a single-use plastic bag ban in Vietnam will soon provide a chance to use these data to measure the effectiveness of such a policy when it does come into effect.

Another finding centered on the informal waste-picking sector, where individuals or small scale networks of informal workers collect and sell recyclable materials, like bottles made from PET. “In places like Indonesia where you have a strong informal recycling network, you actually see less recyclable plastic ending up in rivers,” Brewster said. “That suggests that creating real value for plastic waste, while supporting the informal sector by recognizing their work and enabling political and financial investments to keep their services dignified and safe, ultimately leads to less plastic in waterways.”

Based on their study, researchers offer four key recommendations for reducing plastic pollution in rivers:

- Create value for plastic waste to support a circular economy through policies such as minimum recycled content and bottle deposit fees

- Invest in waste management and recycling infrastructure and services, including the people that provide these services (i.e. invest in waste-pickers)

- Improve standardized data collection to inform upstream prevention actions (i.e., monitoring efforts in rivers before and after policy implementation)

- Enact local and national policies tailored to context while supporting ambitious international frameworks, like the United Nations’ ongoing negotiations for a global treaty to end plastic pollution

The research team has made the one-of-a-kind dataset from the study publicly accessible to enable others to explore new research questions. “Our hope is that others will add to this dataset and draw answers to their own questions about plastic pollution from it,” McCauley said.

Beyond the data, Brewster emphasized the importance of the project’s equitable, community-first design. “It wasn’t just about UCSB collecting data,” he said. “These were local leaders, often in the Global South, collecting meticulous data, building their own capacity for research and getting funding for broader environmental and social projects, from river cleanup technology to education programs and green public spaces.”

In Panama, for instance, the local team used the region’s first autonomous, renewable-energy-powered trash wheel to collect river plastic while gathering data to guide policy and cleanup efforts. “We are working together to clean up our communities and environments, making meaningful local impacts through a collaborative global effort,” said co-author Mirei Endara de Heras, co-founder of Panama-based Marea Verde. “Being a part of this study only elevates those impacts. The data allow us to move beyond the constant battle of cleaning up to really begin to understand the problem and how to stop it in the first place.”

Since 2020, the Clean Currents Coalition has removed more than 7.3 million kilograms of debris (over 4.4 million kilograms of it plastic) from rivers worldwide, while restoring habitats, improving local infrastructure, creating jobs and educating communities about sustainable practices.

“This work is really about turning off the tap of plastic pollution at its source,” Brewster said. “It’s not just cleaning rivers, it’s about doing purposeful science and supporting the communities that are the real leaders that will make this change last.”

To conduct their research, the team received funding from Lynne and Marc Benioff, the Coca-Cola Foundation and the Harris Family Charitable Gift Fund. To learn more about the co-authors and community leaders participating in this research, visit the Clean Currents Coalition website.

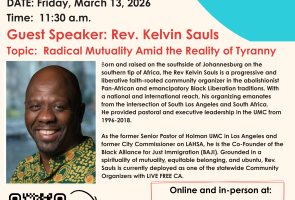

Premier Events

Thu, Feb 26

11:00 AM

Montecito

La Casa de Maria – Lunch and Learn

Sun, Mar 08

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Tue, Feb 24

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Banff Mountain Film Festival World Tour: 2 Nights!

Wed, Feb 25

4:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Career Exploration Fair: For Teens & Young Adults

Wed, Feb 25

5:00 PM

Isla Vista

Forward Ever Backward Never

Wed, Feb 25

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Creative Exploration

Wed, Feb 25

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Salvidoria, Orangepit!, & Magnetize at SOhO

Thu, Feb 26

1:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Shocking History of Electricity in Santa Barbara

Thu, Feb 26

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Anniversary Screening – Connectivity: “Chulas Fronteras”

Thu, Feb 26

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beautiful Borders: Texas-Mexico Crossings in Film

Thu, Feb 26

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with The Mends & Redfish at SOhO

Fri, Feb 27

2:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Opera Santa Barbara presents “Caesar and Cleopatra

Thu, Feb 26 11:00 AM

Montecito

La Casa de Maria – Lunch and Learn

Sun, Mar 08 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Tue, Feb 24 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Banff Mountain Film Festival World Tour: 2 Nights!

Wed, Feb 25 4:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Career Exploration Fair: For Teens & Young Adults

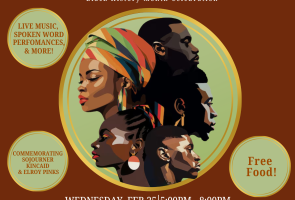

Wed, Feb 25 5:00 PM

Isla Vista

Forward Ever Backward Never

Wed, Feb 25 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Creative Exploration

Wed, Feb 25 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Salvidoria, Orangepit!, & Magnetize at SOhO

Thu, Feb 26 1:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Shocking History of Electricity in Santa Barbara

Thu, Feb 26 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Anniversary Screening – Connectivity: “Chulas Fronteras”

Thu, Feb 26 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beautiful Borders: Texas-Mexico Crossings in Film

Thu, Feb 26 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with The Mends & Redfish at SOhO

Fri, Feb 27 2:30 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.