Santa Barbara County just unveiled a new roadmap to protect those who suffer most from environmental hazards.

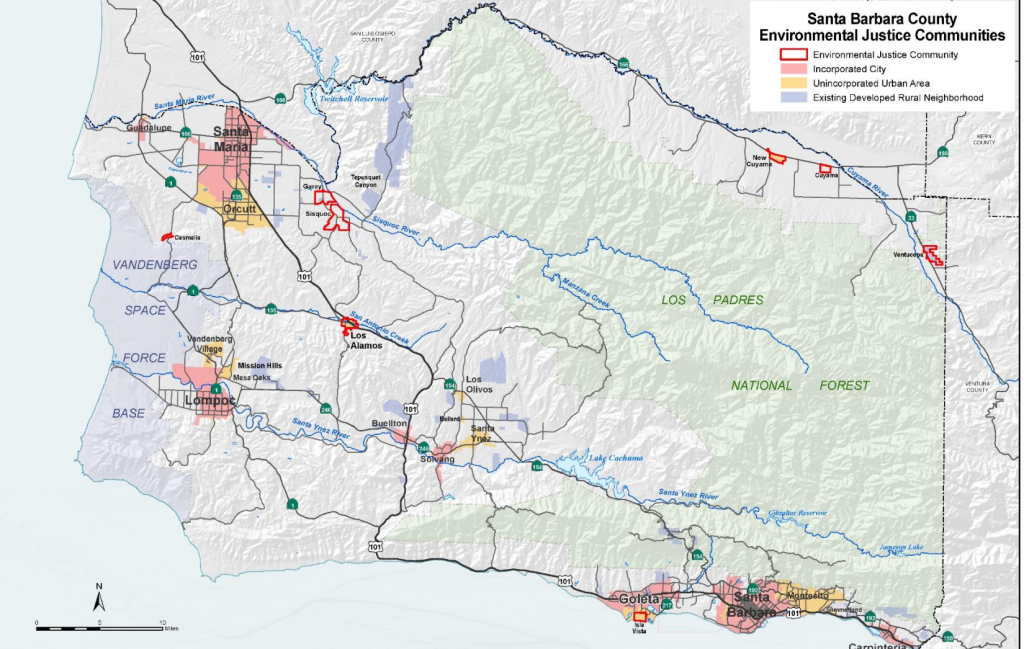

The draft Environmental Justice Element was created through outreach in the county’s “Environmental Justice Communities” (EJCs), or the low-income communities disproportionately affected by pollution and other health risks: Casmalia, Cuyama, New Cuyama, Ventucopa, Garey, Sisquoc, Los Alamos, and Isla Vista.

Environmental justice ensures everyone has the right to a healthy environment and equitable say in the decisions that affect it, which is the main idea behind the element’s objectives and policies, according to the county.

Objectives include reducing exposure to pollution and improving air quality; increasing access to public facilities, physical activity, and healthy foods; promoting civic engagement; and generally expanding services in each community to address individual needs.

Disadvantaged communities usually bear the brunt of pollution and other environmental burdens. They may deal with unsanitary and abandoned store fronts, littered sidewalks, and dirty air or water due to agricultural and industrial operations. Some have high volumes of people, unsafe housing conditions, and inadequate oversight.

Many local residents described their communities positively, as full of good people, or as nice, quiet, friendly and caring. But they are not without issues. Garey, Sisquoc, and Los Alamos, for example, may face negative side effects from exposure to pesticides and oil and gas operations. Residents in Cuyama may deal with over-drafted water resources and water contamination.

Casmalia has a toxic Superfund site, a location contaminated with hazardous waste that the federal government identified for clean up. Isla Vista is overcrowded with housing affordability and safety issues.

People in many of these communities live at least 30 minutes from the nearest grocery store, and a lot of them have sizable Spanish-speaking populations. They all could benefit from expanded public services and outreach.

In response, methods to promote and maintain healthy lifestyles and a clean environment in each community are the backbone of the Environmental Justice Element.

“It’s our first new element in decades,” said Alex Tuttle, manager of the county’s Long Range Planning Division. Tuttle helped present the element at the Planning Commission’s first public hearing for it on Wednesday.

It was a long time coming. Efforts were catalyzed in 2016 by the passing of California Senate Bill 1000, which mandates local governments to integrate environmental justice into their general plans, guides for future decision-making.

Right now, much of the element and its policies are just words on paper. However, if adopted, 15 county agencies, from Behavioral Wellness to the Air Pollution Control District, would have new action items they’d be expected to take on to achieve the element’s objectives. For example, to improve air quality, different agencies are asked to apply for funding to minimize fire ignitions, reduce mobile sources of emissions (e.g. trucks), and assist residents with indoor air filters.

Planning Commissioners Vincent Martinez and John Parke picked the plan apart during Wednesday’s hearing.

The county is already taking actions to address some of these issues, using existing policies under existing elements (other chapters in the county’s General Plan). Martinez’s ultimate question, then, was, “Why do we need this? … Are we just adding to the pile?”

Tuttle said that to address state law’s specific policy requirements related to environmental justice — improving air quality, increasing food access, etc. — the county should, in fact, plan and do more within EJCs.

“I would not say we already have it covered,” he said. “Nowhere is it really articulated in compliance with state law.”

Tuttle noted during the hearing that the element would not impose any new regulations or burdens on development or industry where regulations already exist. What it does do, he added, is identify objectives that are not “out of reach,” nor would “overcommit the county.”

For example, he said, “things like air quality are already pretty heavily regulated.” The new element would not impose any new air quality standards. “What it does do is suggest, perhaps, adding monitoring equipment to an environmental justice community so that air quality can be properly tracked and monitored.”

Other objectives outline better monitoring and enforcement for industrial land uses, disallowing new toxic waste sites, reducing farmworkers’ exposure to pesticides, and increasing access to clean water, to name a few.

Only five people made public comments, including one man, Ed Hazard, representing mineral rights owners on the Central Coast, who was critical of potentially adding more limitations and monitoring to regional oil, gas, and agricultural industries. Others questioned where the money would come from to support the element’s objectives and how it may be realistically implemented. Otis Calef, of the Santa Barbara County Trails Council, asked that trail infrastructure and access be considered in the element, adding that it should pass to “improve the lives of people in Santa Barbara.”

The commission ultimately decided to push the hearing to October 8 to better understand the new element and garner more public input before sending it to the Board of Supervisors for adoption.

“It’s a great-looking package,” Commissioner Parke said, noting that it involved communities that are typically underrepresented. “I just want to be absolutely sure it doesn’t create some unforeseen consequences.”

Learn more about the Environmental Justice Element and how to submit public comments on the county’s website: countyofsb.org/794/Environmental-Justice-Element.

Premier Events

Sun, Jan 11

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 23

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Mon, Jan 05

6:00 PM

Goleta

Paws and Their Pals Pack Walk

Mon, Jan 05

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancient Agroecology: Maya Village of Joya de Cerén

Tue, Jan 06

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Amazonia Untamed: Birds & Biodiversity

Wed, Jan 07

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents the John Jorgenson Quintet

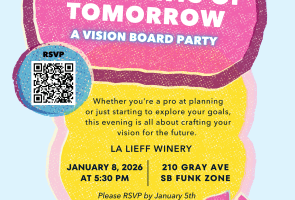

Thu, Jan 08

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Blueprints of Tomorrow (2026)

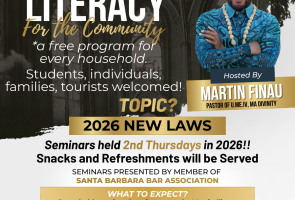

Thu, Jan 08

6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Thu, Jan 08

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Music Academy: Lark, Roman & Meyer Trio

Fri, Jan 09

8:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Herman’s Hermits’ Peter Noone: A Benefit Concert for Notes For Notes

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancestral Materials & Modernism

Sun, Jan 11 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 23 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Mon, Jan 05 6:00 PM

Goleta

Paws and Their Pals Pack Walk

Mon, Jan 05 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancient Agroecology: Maya Village of Joya de Cerén

Tue, Jan 06 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Amazonia Untamed: Birds & Biodiversity

Wed, Jan 07 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents the John Jorgenson Quintet

Thu, Jan 08 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Blueprints of Tomorrow (2026)

Thu, Jan 08 6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Thu, Jan 08 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Music Academy: Lark, Roman & Meyer Trio

Fri, Jan 09 8:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Herman’s Hermits’ Peter Noone: A Benefit Concert for Notes For Notes

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.