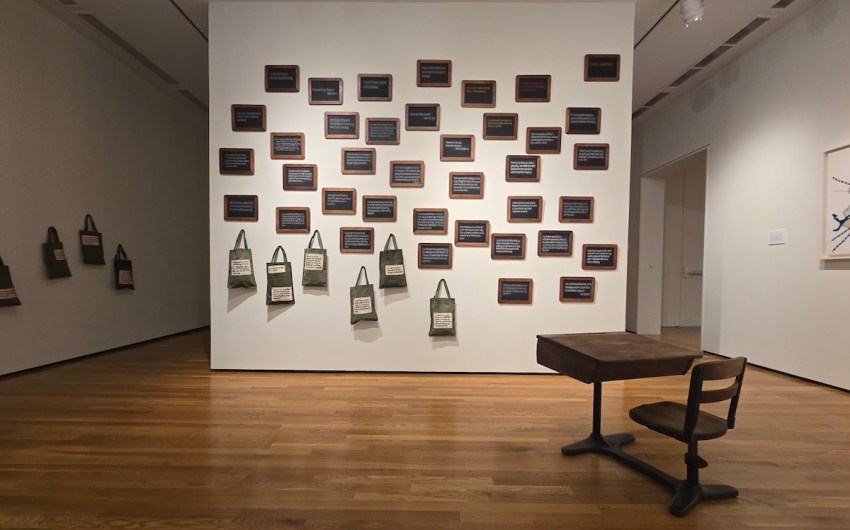

Our beloved Monets are currently having an extended family reunion at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. One of the prized possessions in the vast SBMA permanent collection is Claude Monet’s “Villas in Bordighera” — also a favorite, in part, because the Italian Mediterranean ambience resembles that of Santa Barbara. The Museum’s three other Monet paintings have also been brought out for public view, a rare quadruple Monet moment in public.

But, of course, the big Monet/impressionist news has unfolded with SBMA’s hosting of the major traveling exhibition The Impressionist Revolution: Monet to Matisse from the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA). DMA’s holdings of Impressionist work, that ever popular “-ism” appealing to the art elite and the art suspicious alike, is a rare and fortified treasury in the art world. And as a rightfully proud addendum to the visiting show, SBMA has pulled out a hefty and impressive sampling of its massive holdings of 19th-century French art — including Matisse, Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, and our man Monet — in the additional exhibit Encore: 19th-Century Art from the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

A strong late 19th-century French artistic spirit is in the air and in the building.

Needless to say, this is the biggest blockbuster at SBMA since the major Van Gogh show in 2022, and an ultra-rare chance to get up close and personal with many celebrated paintings in that genre. And it is a major crowd-pleasing genre which will bring in more satisfied customers than, say, the last few intriguing contemporary shows at the museum.

By this point in history, Impressionism is all about eye-friendly art, easy on the senses, yet also with a radical pedigree and origin story. Generally, Impressionism now holds a reputation as a relatively comfy, highly marketable art world unto itself, which has folded neatly into various corners of pop culture and mass marketing byways.

Although it may be considered a separate entity from 20th-century modernism, later artistic movements and iconoclasts owe a debt to the Impressionist ancestry. It remains a critical seedbed for later artistic revolutions and evolutions to come.

That continuum is part of the story with this exhibition. For all of the central focus on strictly defined Impressionist art — a definition that was ever in flux — the show also veers into related offshoots such as Post-Impressionist work, Pointillism, Fauvism, and early rumblings of Expressionist fervor.

Going back to the movement’s youthful rebellious era, Monet’s work was featured in the infamous exhibition of the “Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers etc.,” a pivotal moment of which this traveling show is celebrating its 150th anniversary. After being rejected by the omnipotent Parisian Salon, because of this new art’s daring shift away from moldy norms of precious realism and idealized settings and subjects, the young artists forged their own way. The then-pejorative term “Impressionism” was lobbed by critic Louis Leroy, who lambasted the show, a historic case of critical invective soon rendered laughable.

Despite there being only a handful of Monet works in this selection, he is decidedly the star of the show. The short list runs an intriguing range in his output, starting in his pre-history era of his pre-Impressionist breakthrough canvases “Still Life, Tea Services” (almost traditional) and “The Seine at Lavacourt” (this one actually accepted by the Salon). The title of his 1891 painting “Poplars, Pink Effect” alludes to his priorities, the duality of his interest in natural splendor and the seductive effect of color for its own sake.

Going deep into his reputation as a kingpin and early architect of the movement, the show boasts a pair of canvases from his storied water lily series — two out of some 250 paintings he made in his own private backyard. We see his progression by comparing 1903’s “The Water Lily Pond (Clouds),” still giving us a sense of bearings with a horizon line on top and a clear depiction of said clouds in the watery mirror, and, five years later, his more immersive and flotational-feeling “Water Lilies” from 1908.

Another major figure in the group, the Danish-French Camille Pissarro, is shown as an artist in evolution. His “Place du Théâtre Français, Fog Effect” doubles up the already soft-focus nature of his representation, here amped up and blurred out by fog. But a different effect is seen with the refined and nearly dizzying optical effect of Pissarro’s use of pointillism in “Apple Harvest.”

As launched by Georges Seurat, pointillism was a short-lived branch of the movement, in which prismatic points of light and color conspire to a pleasing tease-the-eye end result. The pointillist vantage also includes work by the genre’s notable proponent Paul Signac.

Other points of interest include Edgar Degas’s first sculpture, “The Masseuse,” in which the sinuous play of limbs and tangled lines resemble his dance studies, and Pierre Bonnard’s “Woman with a Lamp,” an evanescent image with greater focus on the lamp than the visually swimming and ambiguous surroundings.

Off to the left of the common Impressionist style, we find the work of Paul Cezanne’s “Still Life with Carafe,” with its faceted approach to modeling in contrast to the softer edges of classic Impressionist art. He digs into the material nature of his subject, retooling with his fresh eye, rather than detaching. Édouard Manet, touched on via his “Brioche with Pears,” appears as an inspirational elder in this cohort of artists, and path-forger himself who also broke away from the conservative way and painted the everyday with his unique painterly language.

Paul Gauguin was in Tahiti when he created his characteristic Polynesian painting “I Raro te Oviri (Under the Pandanus),” teetering between realism and folk art, fast-and-loose imagery, and in appreciation of unrestrained color and, of course, the female form. Gauguin’s friend, then rival Van Gogh, who was initially plugged into Impressionist spirit before busting out with his more vivid and pre-expressionist palette, is represented by a paler, more soft-lit painting, “Sheaves of Wheat” (painted in the final month of his short life). A variation on his ongoing fascination with fields and harvest, the painting has rhythmic dance of sheaves offset by an almost apparitional appearance.

Some of my favorite pieces in the show are in the Eamons Gallery, host to the “Ever After” selection of paintings in the stages after the Impressionist revolution. Matisse’s “Still Life: Bouquet and Compotier” bears the artist’s signature oblique ideas about composition and a punched-up palette has Impressionist echoes, through his brushwork and appreciation of ambient space and atmosphere as much as the floral subjects at hand.

One artist deserving greater recognition is Alexei Jawlensky, associated with Die Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) movement. His distinctive canvas “Abstract Head: Two Elements” draws on the influences of Russian Orthodox iconography, with a balance of Impressionist and proto-Expressionist elements in the equation.

Pierre Bonnard’s fleshy and semi-voyeuristic (but not in a creepy way) domestic nude paintings beckon in a style all their own. By contrast, more surprising work comes from Edvard Munch’s melting landscape painting “Thuringian Forest,” a soupy hybrid of Impressionist notions and his own angsty style; as well as Piet Mondrian’s loose, dark Dutch — as in “Windmill” — departure from the clean and orderly De Stijl mode he became noted for.

In effect, these paintings represent the aftereffects of Impressionism’s heyday, pushing into new vistas. That same blend of pushing forward while heeding the art historical models prevails in fine art to this day. It’s hard now to think of the words “revolution” and Impressionism in the same breath. This soft-spoken powerhouse of a show doesn’t even pretend to deliver any shock of the then-new. But it’s a formidable balm in our troubled times, right there on State Street. Monet would approve.

The Impressionist Revolution: Monet to Matisse from the Dallas Museum of Art is on view at Santa Barbara Museum of Art through January 25, 2026. See sbma.net for details and tickets (required).

Premier Events

Thu, Feb 26

11:00 AM

Montecito

La Casa de Maria – Lunch and Learn

Sun, Mar 08

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Mon, Feb 23

6:30 PM

Santa Ynez

FREE Concordia Handbells in Concert

Mon, Feb 23

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBCC Big Band Jazz at SOhO

Tue, Feb 24

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Banff Mountain Film Festival World Tour: 2 Nights!

Wed, Feb 25

4:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Career Exploration Fair: For Teens & Young Adults

Wed, Feb 25

5:00 PM

Isla Vista

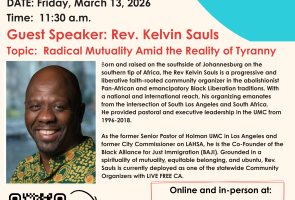

Forward Ever Backward Never

Wed, Feb 25

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Creative Exploration

Wed, Feb 25

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Salvidoria, Orangepit!, & Magnetize at SOhO

Thu, Feb 26

1:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Shocking History of Electricity in Santa Barbara

Thu, Feb 26

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Anniversary Screening – Connectivity: “Chulas Fronteras”

Thu, Feb 26

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beautiful Borders: Texas-Mexico Crossings in Film

Thu, Feb 26 11:00 AM

Montecito

La Casa de Maria – Lunch and Learn

Sun, Mar 08 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Mon, Feb 23 6:30 PM

Santa Ynez

FREE Concordia Handbells in Concert

Mon, Feb 23 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBCC Big Band Jazz at SOhO

Tue, Feb 24 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Banff Mountain Film Festival World Tour: 2 Nights!

Wed, Feb 25 4:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Career Exploration Fair: For Teens & Young Adults

Wed, Feb 25 5:00 PM

Isla Vista

Forward Ever Backward Never

Wed, Feb 25 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Creative Exploration

Wed, Feb 25 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Salvidoria, Orangepit!, & Magnetize at SOhO

Thu, Feb 26 1:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Shocking History of Electricity in Santa Barbara

Thu, Feb 26 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Anniversary Screening – Connectivity: “Chulas Fronteras”

Thu, Feb 26 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.