The failure of banks and savings and loan institutions has a long history in the United States. Most people know something about the bank runs that crippled financial institutions after the stock market crash of 1929, the savings and loan collapse of the 1980s, and many have direct knowledge of the subprime mortgage debacle that roiled the world economy in 2008-09, the negative effects of which were felt unequally for several years thereafter. The subprime crisis required a massive taxpayer-funded bailout — the Troubled Asset Relief Program — to rescue investment banks that had bet heavily on risky derivatives and other unsound instruments. In each of these failures, naked greed, speculation, lax regulation, or outright fraud played a role.

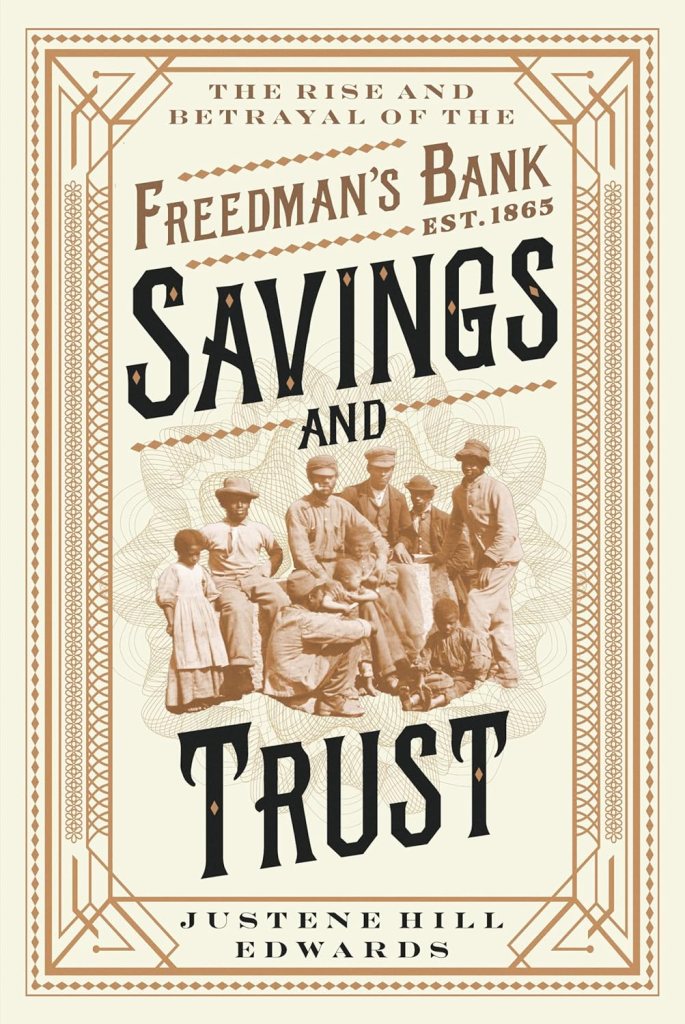

In her marvelous new book, Savings and Trust, scholar Justene Hill Edwards focuses on an earlier bank scandal, that of the Freedman’s Bank, established by an act of Congress and signed into law by President Lincoln in March 1865. The Freedman’s Bank was a savings bank, meaning that its stated mission was different from that of commercial banks or joint stock companies. A savings bank combined civic and economic uplift, and sought to uplift poor people by encouraging them to work and save. The Freedman’s Bank was preceded by banks established by the Union army to hold the deposits of colored soldiers.

Good historians apply a magnifying glass to specific events. They expand our view and show us unexplored details and connections. If the historian happens to be a skilled writer and an adept storyteller, the end product is often revelatory. Justene Hill Edwards is this kind of historian. The Reconstruction era is the context, but she focuses on how the Freedman’s Bank came into being, and the men (all men, to be clear) and circumstances that brought it down. “Historians familiar with the Civil War and Reconstruction eras,” Edwards writes, “are aware of the Freedman’s Bank and its history. But the story of the bank has often been an addendum, or sometimes a literal footnote, in larger accounts of a nation emerging out of the vagaries of war.”

If there was one thing formerly enslaved African Americans desired at the end of the Civil War, it was land. Even though many had no material wealth, enough people understood that land ownership was the ticket to economic freedom and independence, and they also knew from centuries of experience how to cultivate land to produce cash crops and commodities like cotton. Before the Freedman’s Bank came into existence, African Americans often stashed their money in hiding places or entrusted it to a white person.

Of all the altruistic abolitionists, bankers, and philanthropists behind the creation of the Freedman’s Bank, none was more influential than John Alvord, a Congregationalist minister who served as an attaché with Sherman’s Union army. Alvord spent considerable time talking with freed people about what they needed to make the transition from slavery to freedom, and he persuaded powerful and wealthy allies in New York to support a benevolent financial institution dedicated to the unique needs of the formerly enslaved. Alvord appears to have acted with the noblest intentions, but running a savings bank was beyond his ken.

On one level, the Freedman’s Bank was a tremendous success, concrete proof that freed people had the pluck and determination to participate in American capitalism. African Americans were encouraged to save the “small sums” and they did, beyond expectations. The popularity of the Bank spurred its rapid growth, with branches opening throughout the South. As of July 1865, the Bank held $180,000, the equivalent of $3.34 million today. By March 1868, the Bank held more than three and a half million dollars, approximately $76.1 million in today’s currency. So, if the bank was attracting deposits at such a clip, and expanding its operations, what caused its failure? This is the heart of the story. Edwards introduces us to the actors who brought about the Bank’s demise. Although John Alvord was the Bank’s president, he wasn’t a banker by trade, so he relied on men with experience in business and industry, including Henry D. Cooke, the brother of Jay Cooke, a financial titan from Ohio. Henry Cooke served on the Bank’s most influential committee: the finance committee. Along with the decision in 1867 to move the Bank’s main office from New York to Washington, D.C., Cooke’s appointment to the finance committee opened the door to levels of risk-taking that were inimical to the Freedman Bank’s mission of serving the interests of freed people. Through a network of relationships, the Bank’s white principals began catering to the needs and whims of Washington’s political machine. Major malpractice and malfeasance followed.

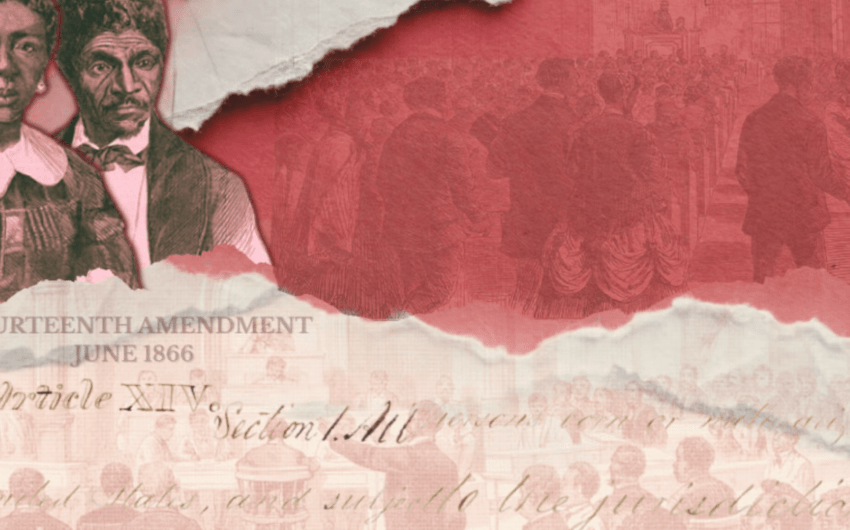

Of particular interest to me was the role played by Frederick Douglass, who in March 1874 became the Bank’s fourth, and last, president. By that year, the Bank’s dire condition was well known. Douglass walked into a disaster. Every unsound and unethical decision made by the finance committee, exacerbated by the Panic of 1873, came home to roost, and even a figure as respected and revered as Frederick Douglass couldn’t pull the Bank back to solvency. Douglass’s involvement with the Bank left a stain on his legacy and contributed to claims from political opportunists that African Americans brought about the Bank’s failure. Edwards debunks such claims: “Of all the loans that the finance committee made, white borrowers accounted for 80 percent of the loan volume, while they were only 8 percent of the account holders.”

As with other financial scandals, official misconduct, greed, lack of oversight, and human shortcomings caused the demise of the Freedman’s Bank. White men walked away, free to rebuild their reputations and wealth while African American depositors lost all or most of their money; the consequences were sadly felt into the early years of the twentieth century.

As with the repudiation of Reconstruction, the fall of the Freedman’s Bank was a tragedy. What began as a vehicle for freedom became a betrayal of trust. “Collectively, we have taken for granted that white wealth was built from Black work and Black ingenuity,” writes Edwards in a fitting summation. “Consider the fact that formerly enslaved people deposited approximately $57 million into the Freedman’s Bank.” In today’s money that’s $1.5 billion. Imagine the lost possibilities, the wealth never invested and built upon, leveraged, and passed generation by generation, family to family. As with most American financial debacles, the profits of a few were valued over the losses of the many.

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.

Premier Events

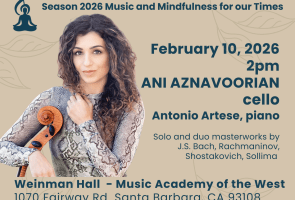

Tue, Feb 10

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation Santa Barbara Season Opening

Mon, Feb 02

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

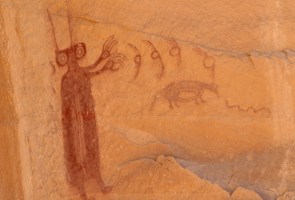

Lecture: Late Archaic Rock Art of the Desert Southwest

Tue, Feb 03

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ruckus and Davóne Tines, Bass-Baritone

Wed, Feb 04

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Filmmakers HUMP DAY Comedy Night

Wed, Feb 04

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

CAMA Masterseries: Emanuel Ax, Piano

Thu, Feb 05

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

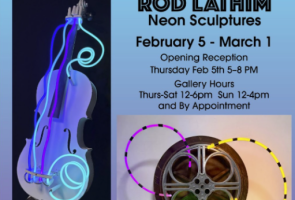

Opening Reception: Rod Lathim’s “LIT”

Thu, Feb 05

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

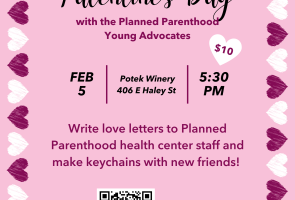

Palentines Day with PPYA

Thu, Feb 05

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

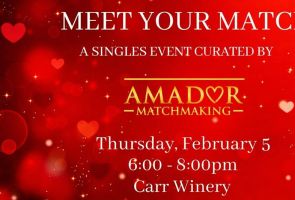

Meet Your Match: A Curated Valentine’s Party for Singles

Fri, Feb 06

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

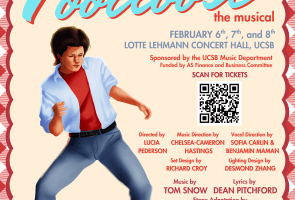

Shrunken Heads Production Company Presents “Footloose: The Musical”

Fri, Feb 06

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

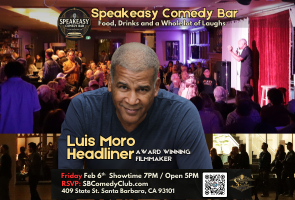

Luis Moro Santa Barbara Comedy Show

Fri, Feb 06

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Dark Matter Under the Gravitational Lens

Tue, Feb 10 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation Santa Barbara Season Opening

Mon, Feb 02 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lecture: Late Archaic Rock Art of the Desert Southwest

Tue, Feb 03 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ruckus and Davóne Tines, Bass-Baritone

Wed, Feb 04 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Filmmakers HUMP DAY Comedy Night

Wed, Feb 04 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

CAMA Masterseries: Emanuel Ax, Piano

Thu, Feb 05 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Opening Reception: Rod Lathim’s “LIT”

Thu, Feb 05 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Palentines Day with PPYA

Thu, Feb 05 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet Your Match: A Curated Valentine’s Party for Singles

Fri, Feb 06 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Shrunken Heads Production Company Presents “Footloose: The Musical”

Fri, Feb 06 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Luis Moro Santa Barbara Comedy Show

Fri, Feb 06 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.