Multiple owl species live quietly among us — often unseen, almost always unheard. And in a few weeks, the Santa Barbara community will gather to honor one in particular.

On February 7, the Santa Barbara Audubon Society (SBAS), in partnership with the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, will host a celebration of life for Max, a great horned owl who spent nearly three decades as an avian ambassador — and, in the process, became one of the most recognizable raptors in Santa Barbara.

Max died recently at age 27, a venerable lifespan for a great horned owl. Though he could fly and hunt, Max could not survive in the wild after imprinting on humans as an owlet. Instead, he lived at the museum’s Audubon Aviary, where he served as a cornerstone of the Audubon Society’s Eyes in the Sky (EitS) program, introducing thousands of students to raptor ecology through classroom visits and public events across the county.

“Max was one of the original EitS raptors and a local celebrity,” said Janice Levasheff, Santa Barbara Audubon Society board president. “Even to this day, many adults still remember Max from his visits to their classrooms while they were in elementary school.”

The Life of Max

After falling from his nest and imprinting on humans, he was deemed nonreleasable and adopted into the Audubon Society’s education program. Over the years, he was introduced to thousands of students to raptor ecology at an appropriate arm’s length.

“He had an incredible positive impact on countless members in our community,” said Dr. Katherine Emery, executive director of the Santa Barbara Audubon Society. “He brought wonder and joy to learners of all ages and was a foster parent to dozens of orphaned owlets.”

That role — foster parent — is among the least known aspects of Max’s legacy. Great horned owls will readily raise unrelated chicks if placed in their care. Max helped rehabilitators return orphaned owlets to the wild, quietly extending his influence far beyond the aviary.

The partnership that made Max’s long life possible was also unusual. While the aviary sits on museum grounds, the birds are cared for by the Audubon Society, which operates as an independent nonprofit separate from the national Audubon organization.

“We appreciate the partnership between the museum and SBAS that made possible a beautiful and safe Audubon Aviary setting for Max to live and be admired,” Emery said.

There are also some great perks of being an owl town. The apex predators of the night keep rodent populations in check and hold together fragile food webs. In addition, dissecting owl pellets — the compact bundles of fur and bone regurgitated after feeding — is a staple of environmental education. Inside are intact skeletons of mice, voles, and small birds, tangible proof of ecological connection.

“It’s an amazing tool,” Emery said. “Kids can learn what owls are eating, how ecosystems work, and how everything is connected.”

That educational mission is a big part of the Audubon Society’s work, which includes bird walks, conservation advocacy, citizen science projects like the Christmas Bird Count, and public programs across Santa Barbara County.

“Our goal is to protect birdlife and habitat and connect people with birds through education, conservation, and science,” Emery said.

A City of Owls

Max’s life — and death — comes at a moment when interest in Santa Barbara’s urban wildlife is rising. From a bear wandering onto UCSB’s campus back in April to an owl caught in a car grille in December, residents are increasingly aware that the city’s human footprint overlaps with a much older ecological map.

According to Mark Holmgren, longtime ornithologist and coordinator of the Santa Barbara County Breeding Bird Study, seven owl species are known to breed in Santa Barbara County. Four of them — including great horned owls and western screech owls — are widespread enough to be publicly mapped. The remaining three are considered sensitive, their nesting locations intentionally withheld to prevent disturbance.

“What I do is take public input to document the breeding of not just owls, but all of the 180-plus species that breed in Santa Barbara County,” Holmgren said. “We have a cool tool to reveal that information.”

That tool — a countywide breeding bird map — contains more than 13,800 records. In other words: If you think you haven’t seen an owl in Santa Barbara, it’s probably because the owl saw you first.

The mysticism of owls is thanks to evolution. They fly silently on velvety feathers that dampen air turbulence. Their eyes face forward for depth perception, fixed in place by bone, forcing them to rotate their heads instead — up to 270 degrees.

For Dr. Emery, executive director of the Santa Barbara Audubon Society, that combination of power and mystery never gets old.

“One of the most magical times I saw great horned owls was up close at our protected open space at Lake Los Carneros in Goleta,” Emery said. “As dusk came, the adult soared out of the trees to be followed shortly after by three large plump young owls.”

“All four creatures landed a short distance away and then, swiftly and silently, flew off across the open space to, I presume, hunt and enjoy the wilderness,” she said.

Celebration of Life

Max’s celebration of life will take place February 7 from 3 to 5 p.m. in Fleischmann Auditorium at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. The event is free to attend and open to the public.

Premier Events

Fri, Mar 06

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07

9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sat, Mar 07

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

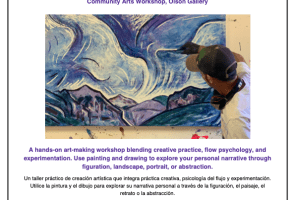

2-Day Expressive Painting Creative Workshop

Sun, Mar 08

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

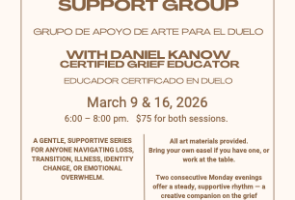

Mon, Mar 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Fri, Mar 06

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

Fri, Mar 06

8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Sat, Mar 07

12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Spring 2026 Healing Arts Faire

Sat, Mar 07

7:00 PM

Carpinteria

The Magic’s In the Music

Sat, Mar 07

7:30 PM

Goleta

UCSB Arts & Lectures Presents Arturo Sandoval Legacy Quintet

Sat, Mar 07

7:30 PM

Goleta

Jazz Concert with Wayne Bergeron

Sun, Mar 08

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Fairytale Weekend at the Zoo

Sun, Mar 08

1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Craftivists “Resist with Love KNOT Hate Knit-In

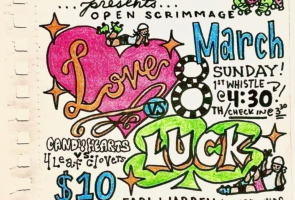

Sun, Mar 08

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Brawlin’ Betties: Love v. Luck Scrimmage

Sun, Mar 08

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents Natalie Gelman & Mark Legget

Fri, Mar 06 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07 9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sat, Mar 07 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

2-Day Expressive Painting Creative Workshop

Sun, Mar 08 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Mon, Mar 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Fri, Mar 06 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

Fri, Mar 06 8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Sat, Mar 07 12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Spring 2026 Healing Arts Faire

Sat, Mar 07 7:00 PM

Carpinteria

The Magic’s In the Music

Sat, Mar 07 7:30 PM

Goleta

UCSB Arts & Lectures Presents Arturo Sandoval Legacy Quintet

Sat, Mar 07 7:30 PM

Goleta

Jazz Concert with Wayne Bergeron

Sun, Mar 08 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Fairytale Weekend at the Zoo

Sun, Mar 08 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Craftivists “Resist with Love KNOT Hate Knit-In

Sun, Mar 08 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Brawlin’ Betties: Love v. Luck Scrimmage

Sun, Mar 08 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.