The Tea Fire Devastates the Bohemia of Mountain Drive

The Phoenix Rises

Fire has always loomed as the great predator in the daily life and legend of Mountain Drive. Last week it looked like fire had finally won.

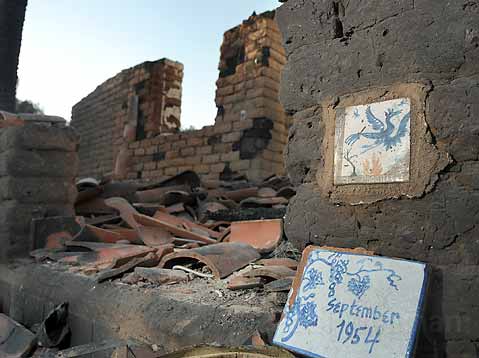

The Monday after the Tea Gardens fire rushed down Mountain Drive and along Coyote Road, destroying at least 22 homes there, I walked through the broken adobe and tile rubble with Kathy Neely, a longtime member of this tightly knit artistic neighborhood. She picked up one tile reading “September 1954.” Her late father-in-law, the potter Bill Neely, one of the founders of this sometimes notorious artistic colony, had created it as a kind of plaque to commemorate his family’s house surviving the first great conflagration to sweep through the area, the Coyote Fire. Now-as we stand in the charred ruins of the house Bill built with his own hands, the house where Kathy’s husband, Chris, grew up, and where they raised their own children, Rosie and Ryan-she put the tile back down on the charred adobe wall and said, “This house was once so alive. I want to have a wake for my home.”

A lot of homes that once were very alive went down in this fire. The litany of victims’ names reads like a who’s who of the old S.B. artistic gentry: Among others, the Robinson family lost four homes, significant because architect Frank Robinson was one of the original settlers, and designed many of the homes here; writer Lucas Lackner was burned out of a famous highly crafted home-though the original Lackner family house down the block, and now occupied by his brother Tom, survived. Artist and UCSB art professor emeritus Gary Brown lost his home and a wealth of great paintings and books.

The fire that began at about 6 p.m. at the Tea Gardens moved to the west. “The winds came whipping through here,” said Chris Neely, a well-known jeweler, “which actually kept the flames down.” Once the fire hit the intersection edge of two ravines, however, it veered off, even though the vegetation there had been dutifully trimmed. The fire rushed back up toward Mountain Drive and Coyote Road, turning merciless.

Since the Mountain Drive community began to form in the late 1940s, the area has experienced three eerily similar fires: the Coyote in ’64, the Sycamore in ’77, and now the Tea Fire. This history has marred the consciousness of Mountain Drive denizens, making them acutely aware of that element’s wrath. Kathy’s guest house has singe marks from the Coyote Fire. And her daughter has had continuing dreams of fire for most of her life. In fact, it was a fire that spread through the ridges of the hills in the late ’40s, prosaically called the Fire on the Hills, which allowed the writer Bobby Hyde to buy a large parcel of charred former estate lands. Legend has it that he supported himself for years by selling tracts of land to artistically inclined friends.

Many of the new residents were like Bill Neely, who, after sojourns in Europe and Mexico, was disgusted with the American postwar consumer culture. Neely teamed up with Hyde and Frank Robinson and, by 1954, they were working on each other’s homes. Hyde had a tractor he called Daisy that Chris and his little friends loved riding on as the roads and plots were leveled for the adobe brick houses, many by Chris’s mom. They were soon joined by other like-minded cultural refugees. Eventually, Mountain Drive became known as the bohemian center of Santa Barbara.

Throughout time, Mountain Drive developed a culture of its own, a culture of “pageantry,” as Chris put it. And they turned some little-known dates into events of exuberant celebration: Twelfth Night, Robert Burns’s Birthday, Winter Solstice. Mountain Drivers also invented the hot tub and the Renaissance Fair at their annual Pot Wars. (Ceramics, not dope, though there seemed to be no shortage of the latter, either.) “I remember sitting in my parent’s kitchen where Joan Baez was singing,” Chris said. “I met Lawrence Ferlinghetti there.” Mountain Drive was then a wayfaring station for hipsters traveling between San Francisco and Los Angeles. In 1964, the film director John Frankenheimer memorialized the annual Mountain Drive grape stomp in his creepy psychological thriller Seconds, which was shot on location right after the Coyote calamity.

Community celebrations changed during years that weren’t always idyllic (alcohol and bohemian manners can create fallout), but the spirit of joyful neighborly camaraderie never withered as the generations passed the land forward. Today, that spirit centers on Jeff Neely, the youngest of Bill’s kids, who remembers the esprit de community with a lot of happiness. “My mother died when I was three,” he said. “So I was raised in all of these houses.” Jeff, paraplegic since a car accident in the late 1970s, survived nicely with wheelchairs and lifts on the rugged terrain of Lower Hyde Road until he was hospitalized with pneumonia. While he was away, the neighborhood got together and built him a new home, insulated and everything. “It even had a real stove, the first one I ever had in my adult life,” he said.

Last Thursday, Jeff’s neighbor came over in the gusting winds to say there was fire on the mountain. After Jeff rolled out to the driveway to assess the situation, he announced, “We should go now.” He got into his big van and led the way down to shelter. But Jeff was among those who returned to nothing. Some tiles, metal pieces, and an oppressive smell of green wood and neighborhood memories turned to ash.

The next morning, the Neelys’ kids came back to the mountain to help, eventually bringing a water truck owned by the Santa Barbara Pistachio Company to put out any lingering embers. Ryan scouted the neighborhood. “It wasn’t seeing who was gone, it was seeing who was left,” he said.

And it is here where hope still exists for Mountain Drive. Chris thinks the whole place will be green by spring, and he’s never in his life been able to see into the canyon that separates them from Westmont College. The community has taken heart from the fact that architect Jeff Shelton has volunteered his services to rebuild in the spirit of the land and its independent people. “Frank Robinson was my mentor,” said Shelton. “I’ll be able to repay him.” Shelton prizes alternative approaches to building and feels that America might now be willing to embrace such Mountain Drive ideas as “salvage chic, sustainability, and simplicity.”

Last Monday, people continued to gather in the ruins. There were tears, but also jokes. Folks were worried about Jeff. I asked if he thought things would come back. “I hope so,” he said. “I want to say, ‘I know so,’ but there’s a lot that’s gone. The whole neighborhood has come together before. So let’s say I hope so.” A crew of friends was filming him for a submission to the TV show Extreme Makeover. “We’ll show them extreme,” quipped Mark Serungard, standing near a collapsed wall with one of Bill Neely’s tiles still embedded in the adobe. This one read “Phoenix.”

For assistance, including home, computer, and tax-deductible gifts for Jeff Neely, email teafirerelief@gmail.com.