Backcountry Ramble

Trekking with a Group of Carpinteria Lifeguards and Channel Islands Guides

The loud, rolling warble that penetrated the San Rafael Mountains halted the six of us while backpacking the Lost Valley Trail in the Los Padres National Forest. As impressive as that sonic boom was while absorbed by the steep sandstone crags and smothering chaparral, it was soon forgotten just minutes later by a lone California condor soaring directly over us while we traversed the serpentine spine of Hurricane Deck.

Backpacking the Santa Barbara backcountry isn’t just an escape. It’s a trek toward the unexpected, where natural wonders potentially lurk around every bend in the trail, every manzanita, river crossing, or sweeping potrero. That solitary condor made several passes over us, but in a sudden instance, North America’s largest flying landbird vanished above lofty ridgetops and a puff of cumulous nimbus.

Six of us — Forrest, Solomon, Zack, Alex, Sean, and I — a merry band of beach lifeguards from Carpinteria and kayak guides at the Channel Islands National Park, hatched a plan for a winter backcountry trek beginning along Highway 154, and finishing in the sweeping grasslands of the Carrizo Plain National Monument. For a seven-day ramble, the distance wasn’t far, about 70 miles across three mountain ranges and two rivers, with plenty of bushwhacking in between.

Self-Propelled

I’m not much of a step keeper, but over those seven days, I became obsessed with one foot in front of the other, and how many steps were required over the seven-day slog from dense chaparral to those semi-arid grasslands.

- Dec. 1: 9.5 miles — 24,271 steps

- Dec. 2: 8.1 miles — 20,459 steps

- Dec. 3: 8.4 miles — 20,569 steps

- Dec. 4: 10 miles — 26,472 steps

- Dec. 5: 14.2 miles — 35,821 steps

- Dec. 6: 5.9 miles — 15,557 steps

- Dec. 7: 8.3 miles — 19,779 steps

- Total steps: 162,928

Some steps were tougher and steeper than others, some more memorable. Some days, the steps felt like they wouldn’t ease. Yet other days were longer but were filled with sounds of the forest, cool winds whistling through the canyons, and water streaming through all the seasonal tributaries. It was also the sounds of silence that were evident in the carved-out sandstone cathedrals: wind and water naturally sculpting the rugged topography. These natural wonders had all of us appreciating each step across portions of the Transverse Ranges.

Falling for a River

Fall colors also decorated the lifeblood of the forest. Before reaching the Sisquoc River, its seasonal palette still held true as brilliant yellow, red, and orange hues flushed toward the winter solstice. Fall colors are a natural wonder not readily seen in Santa Barbara County, but on a river on the Wild and Scenic system like the Sisquoc, its steady, uninhibited flow harbored sturdy forests of cottonwood, sycamore, and California bay trees. While the backcountry revealed its annual splendor tucked away in the San Rafael Wilderness, brilliant reflections mirrored in the many tranquil side pools along the Sisquoc, just a backpacker’s trek away.

As we descended the rolling, gritty spine of Hurricane Deck, those fall colors drew us to the South Fork of the Sisquoc. Its cascading flow quenched the thirst of six parched backpackers. As we rinsed off layers of trail dust, the sound of the river also rejuvenated our spirits, our strides suddenly bounding toward the cobbled runnel.

Two nights on the free-flowing river were filled with hikes up and down the Sisquoc and its many side canyons, followed by raucous card games by the fire. After those two nights, all six of us were anxious to continue northeast, ascending the Sweetwater Trail to the Salisbury Potrero. After reaching the spine of another ridgetop, the stage was set for the path ahead. In 24 hours, we would be camped near Caliente Peak, the tallest mountain in San Luis Obispo County at 5,106 feet.

Riders of Rohan

Conveniently perched on a knife ridge in the Caliente Mountains, the views and our perspective of the surrounding region were stunning. To the south was Big Pine Mountain at 6,800 feet, the highest summit in the Dick Smith Wilderness of the Los Padres National Forest. To the east was Mount Pinos, the highest summit in the National Forest at 8,847 feet. The Sierra Mountains loomed on the northern horizon. Just behind us, to the west, was Caliente Mountain. Between the Caliente Mountains and the Temblor Range to the northeast was the last of California’s semi-arid grasslands, the Carrizo Plain National Monument.

The six of us were ensconced in a unique swath of California biodiversity. Before sunrise, as pink and orange hues swept across the eastern horizon, Sean and Zack blasted “The Riders of Rohan” from the epic Lord of the Rings. It felt appropriate while we were swaddled in our sleeping bags, morning dew beading up and rolling into the arid chaparral. The panoramic view was mesmerizing as we trekked toward Soda Lake, the largest natural alkali lake in Central and Southern California. Our ride back to Santa Barbara was awaiting our arrival on the grasslands. We were leaving three mountain ranges and two rivers in our wake, while being swallowed up by the teeming veld. From the coastal range to the plain, we connected with several different backcountry biomes, one melding into the other. It felt far away, but it really wasn’t far at all.

Premier Events

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03

8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

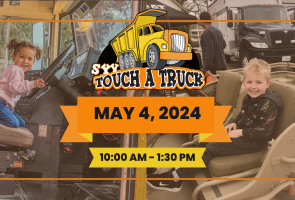

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Solvang

Touch A Truck

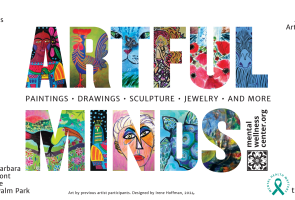

Sat, May 04

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Mental Wellness Center’s 28th Annual Arts Faire

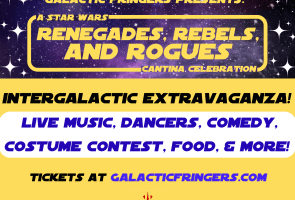

Sat, May 04

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Community History Day

Sat, May 04

3:00 PM

Solvang

The SYV Chorale Presents Disney Magic Concert

Sat, May 04

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

A Star Wars Cantina Celebration: Renegades, Rebels, and Rogues

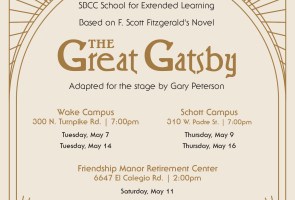

Tue, May 07

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Theatre Eclectic Presents “The Great Gatsby” – Wake Auditorium

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03 8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Solvang

Touch A Truck

Sat, May 04 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Mental Wellness Center’s 28th Annual Arts Faire

Sat, May 04 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Community History Day

Sat, May 04 3:00 PM

Solvang

The SYV Chorale Presents Disney Magic Concert

Sat, May 04 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

A Star Wars Cantina Celebration: Renegades, Rebels, and Rogues

Tue, May 07 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.