The Ultimate Transport

An Essay on Into Great Silence

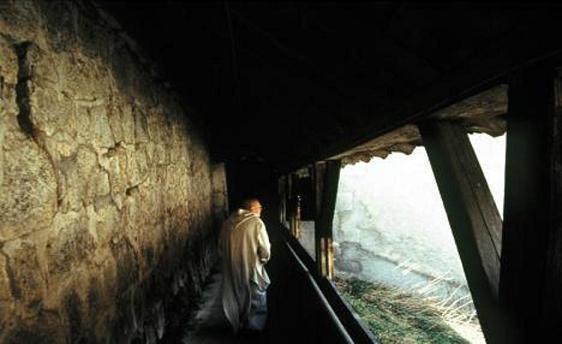

It begins as a shock. A hooded figure is

seated in the dark, so close to us he might be a piece of wood.

Flames flicker here and there against a field of black. We pull

back and see a figure in all white, head down, in a bare room.

There’s no patter, no background music, very little movement. The

camera breathes it all in in long, unswerving takes. You’ve entered

another world in this silent, snowbound cluster of small cells.

Each unworldly shot is a still life that says there’s still

life — vibrant, shifting, human life — in this other world; the

only thing that’s likely to move is you.

And very slowly, as the scenes go on — pealing bells, a monk

carefully snipping some fabric, another one reading a book — you

begin to see the textures in the wood, to notice the slanting of

the light, to make out sunlight and birdsong as you would never do

at home. The film starts to work on you — and in you, too — as its

subject might. You feel a clock ticking, a bee buzzing all around

you. The sound of monks gathering for prayer is thunderous. And

then one of them breaks into song and the sound is ineffably

sweet.

Into Great Silence (or The Great Stillness, as

its title was in German) is like no other movie you’ve ever seen,

though it has some of the slow attentiveness of a Terrence Malick

epic, something of Andrei Tarkovsky’s uncompromising intensity. It

is more a meditation than a film, really, a 162-minute observation

of life in La Grande Chartreuse, a charterhouse of the Carthusian

order of Catholic monks in the French Alps. There is no story, no

script, and certainly very little in the way of characterization.

Some viewers may run out screaming, as from a Noh drama, hungry for

movement and color of a more conventional kind. Others will find it

moves them as a prayer might; till a heart of stone, as the film

puts it, until it becomes a heart of flesh.

The documentary, directed by Philip Gröning (who waited 16 years

for a green light from the monks, and then was allowed to come in

alone and live with them for several months, shooting and recording

by himself with no artificial light), was called “exhilarating” by

Variety, and “entrancing” by the New York Times.

It won a Special Jury Prize at Sundance and was nominated for a

European Film Award. And now it enjoys its West Coast premiere at

UCSB’s Campbell Hall, next Monday, March 5 at 7:30 p.m.

The point of monasticism is to take you out of the world of time

(and change and loss) and back into the realm of changelessness.

The anonymous monks we follow through their seasons in the film,

therefore, do very little other than what their counterparts would

have done 900 years ago (or, in fact, what their Zen colleagues are

doing around me in Kyoto, where I write this). They chop wood and

kneel on bare floors to pray. They feed the local cats and pray

some more. They wheel a deafening trolley through the silence to

deliver lunch through a slot in every other monk’s cell. When, once

a week, they are allowed to take a walk (but not to eat or drink or

enter a secular house), you suddenly feel a wild release as the

monks clatter out into the sun and gossip and play in the snow and

talk about other monasteries like boys on holiday.

A monastery, and a monastic film like this, teaches you how to

see. It also leads you into a world of almost unimaginable

surrender. In one of the memorable scenes in the movie, we watch a

very elderly monk, almost audibly huffing and nearly falling in the

thick snow, working and working to shovel clear a small space in

the depths of winter. He all but kills himself in the process, you

feel, and yet all the effort is explained when, one season later,

the seeds he’s planted on the bare plot begin to shoot up.

It’s a metaphor, in short, and a monastery teaches you to see

everything metaphorically. The monks briskly cutting one another’s

hair are trimming one another’s vanity and claims to individuality.

Their white or black cloaks render them all but indistinguishable

from one another. Toward the end, one blind monk says he sees the

taking of his sight as a blessing; everything’s an adventure when

you’re in love. There are many other movies that could have made

about a community of hermits, and this one chooses not to explore

who these men are, what they’ve left behind them, or what comes to

them in the long, dark nights. It chooses not to dwell on doubt or

charity, and for the inner dramas beneath the surface stillness

you’ll have to turn to Thomas Merton. Yet instead of developing, it

deepens. And instead of giving us an external portrait of what a

monk’s life looks like, it takes us into that very life, so we see

and feel it from within. True to the monastic setting, all barriers

dissolve.

At intervals through the film, a sentence from scripture comes

up on screen (most often the single line, “You have seduced me, O

Lord, and I have let myself be seduced”), the same few sentences

recurring like the pealing bells. But this is not a film about

Catholicism so much as about the relationship any of us can have

with the invisible. At certain points, each of the monks just

stands before the camera, looking into it, and in each pair of eyes

you see a whole epic of light and shadow.

I have spent much of my adult life in a Benedictine monastery up

the coast, and in more than 16 years of staying as a visitor, and

sometimes living in the cloister, I’ve found there is no more

exciting and transporting journey the modern world has to offer.

The stony, silent cloister discovered in this film during midwinter

could not, of course, be more different on the surface from the

expansive radiance of Big Sur. But the beauty of a film like this

is that it takes you beyond names and places and dates to something

we can all recognize when we just sit still.

The point of a motion picture is to take you somewhere, and show

you the world you thought you knew in a radically different light.

Into Great Silence may bore or confound some, but for

those with a taste for silence, it can take you into a far-off

world that is as close as your own heartbeat. Before you know it,

you’re somewhere — someone — else.

4•1•1

Into Great Silence makes its West Coast premiere at

UCSB’s Campbell Hall on Monday, March 5 at 7:30 p.m. Call 893-3535

or visit www.artsandlectures.ucsb.edu

for more information.