Feeling the Future

Eco-Philosopher Joanna Macy on Interdependence, Politics, and Poetry

The hour is striking so close above me, / So clear and sharp / That all my senses / Ring with it. / I feel it now: there’s a power in me / To grasp and give shape to my world.

– Rainer Maria Rilke

Teacher, lecturer, and activist; scholar of Buddhism, deep ecology, and systems theory; speaker to the social, psychological, and spiritual issues of the nuclear age; Joanna Macy wants no less than to transform the way we understand our world. The author of Despair and Personal Power in the Nuclear Age, World as Lover, World as Self, and Coming Back to Life: Practices to Reconnect Our Lives, Our World, Macy sees the era in which we live as a pivotal time – one in which human civilization will either succeed or fail in making the shift from industrial growth and economic interest to self-sustainability. Success, she believes, lies primarily in our ability to retrain ourselves to think not in terms of our own short lifetimes, but on behalf of the many generations that will follow us. Her name for the time in which we live is “The Great Turning” – a revolution not just within the realm of politics, but within the realm of thought. What follows is a conversation between Macy and Elizabeth Schwyzer, Associate Arts Editor at the Independent.

I hear you’ve just returned from a retreat in the Pacific Northwest.

Yes, it was a 30-day immersion in the wilderness along the coast, devoted to looking at and connecting with the needs of future generations. That’s what I’m going to be talking about in Santa Barbara – The Great Turning – which is just the name I use for the transition from an industrial growth society to a life-sustaining society. This is a vast revolution that affects every part of our lives and our thinking, and it definitely comes from – and indeed requires – a sense of connection with future generations. That’s what we were practicing and looking at on the retreat. It really helps to get away from email and cell phones and all those technologies that pull us into short-term thinking.

For those of us who may not have 30 days to spare, is there a way to access that kind of awareness – I guess you could call it longer-term thinking?

I call it deep time, and it’s really very much available to us as humans on this planet, because our ancestors had it. Indigenous peoples and surviving indigenous cultures have it and, until quite recently, that way of thinking was the norm. But within an industrial growth society, the power of market forces – particularly the maximization of corporate profit and the way market shares are measured, quarter by quarter – drives us into short-term thinking where we’re willing to discount the future for the sake of the present. That experience of time and that orientation to time in our political economy is destructive to the world’s natural systems.

Where do you turn for models of deep time?

First, we know that it’s possible to think this way. Then there are practices in the work I have developed. But you don’t need to turn to that; these lessons are in most spiritual traditions and earth traditions, and in the deep ecology movement. It’s about expanding your perception of time to include more than your lifetime; it’s a question of realizing what the acceleration of time is doing to us, and realizing that there is an alternative. You can see how deep time was practiced by our ancestors; they erected great monuments of art and learning that would never be completed in their lifetimes. We can practice seeing our lives from this point of view.

What was your in-road to this way of thinking?

You know, I found my way into this through working on the issue of nuclear waste. I was very dismayed, to put it mildly, to see what we were spewing into the environment that would have an impact on thousands of future generations. This must be a sick relation to time that would motivate us to do such a thing for immediate financial gain. Of all the things I have done in my life, Elizabeth, this has been the most uplifting, energizing, and revitalizing, because I realize that this is our birthright: to live in relation to our ancestors and to all future beings. I look forward to seeing how living in this way can empower us to take part in this revolution. Some call it the ecological revolution. I call it The Great Turning. Whatever its name, it’s a privilege to be alive at a time when we can take part in it. A sense of an expanded time frame for our lives can make a huge difference to our energy, our morale, and our power to take action in the world.

You often work with political and social activists; no doubt there are those who find some of this thinking frustratingly abstract, those who want concrete action. My boyfriend, who is an environmental advocate, had this reaction to Paul Hawken when he spoke about similar topics a few months ago at the same theater in Santa Barbara where you will be speaking. What would you say to such a reaction?

I wouldn’t try to preach at him, but I would certainly try to put some wind in his sails. It might help to see that even in this kind of political activity there are a lot of deceits. When I come to Santa Barbara, I’m going to be talking about how this revolution has three main dimensions to it. One of them is these ‘holding actions’ that slow down the growth of market society. Most of the work we associate with activism is aimed at slowing down the destruction being wrought by this political economy. But that’s not all there is, because even if we won all those battles, it wouldn’t be enough; we have to have other ways to attack the problem. And that is what is happening on the community level. None of this is being reported on the corporate media level. I have had the same experience as Hawken reports in his latest book, Blessed Unrest – I see unsung heroes and actions around the world that are happening under the radar of the corporate-controlled media, actions that are unparalleled in human history. The third dimension is a shift in consciousness derived from a spiritual and perceptual revolution, and that’s where I’d put the requirement for deep time. What’s your boyfriend’s name?

Travis.

You see, Travis, even if he doesn’t admit it to himself, is working on behalf of future generations; he’s not doing it for his own benefit. This is amazing. This gives the lie to so much on which our political economy rests. Travis himself – his life – rests on something else.

It can sound like whistling in the dark if you don’t admit that we can blow it, and may well not succeed in pulling it off. My god, what we’re losing in terms of the great forests – the Amazon and the Congo, the plankton in the seas, the viability of the climate – we could go under before the structures and systems that we put in place can really kick in. So we live with uncertainty, and yet look at him, he’s working even though he knows there is no guarantee that this can save us.

If we did succeed, what would a life-sustaining civilization look like?

Well, you know, we can’t really tell too clearly, because it’s going to emerge synergistically as we put the pieces in place, like new systems of growing food and holding the land and green building and new forms of decision-making and currency. As we put these in place they’re going to be emergent properties, but we know – and this is one of the things Hawken would agree with – we know that it has to take care of everybody. There won’t be winners and losers. We know that. And we have to live within the limits of what the earth can afford; we know that. And we know we have to use incredible technologies to harness the power of the tides and the wind and the sun, and that these systems will have to work for all and not only for a small number; we know that. And we know that we can’t have our lives dictated by greed and corporate organizers whose sole interest is profit and market share; we know that, and so we can feel kind of interested, really curious, and really optimistic that so many people are seeing the necessity for this kind of equity. It’s a big adventure. We’re not saying that it’s a sure thing, but what else do you want to do with your beautiful, precious life?

Paul Hawken writes, “What it takes to arrest our descent into chaos is one person after another remembering who and where we really are.” How do we reconnect with those memories?

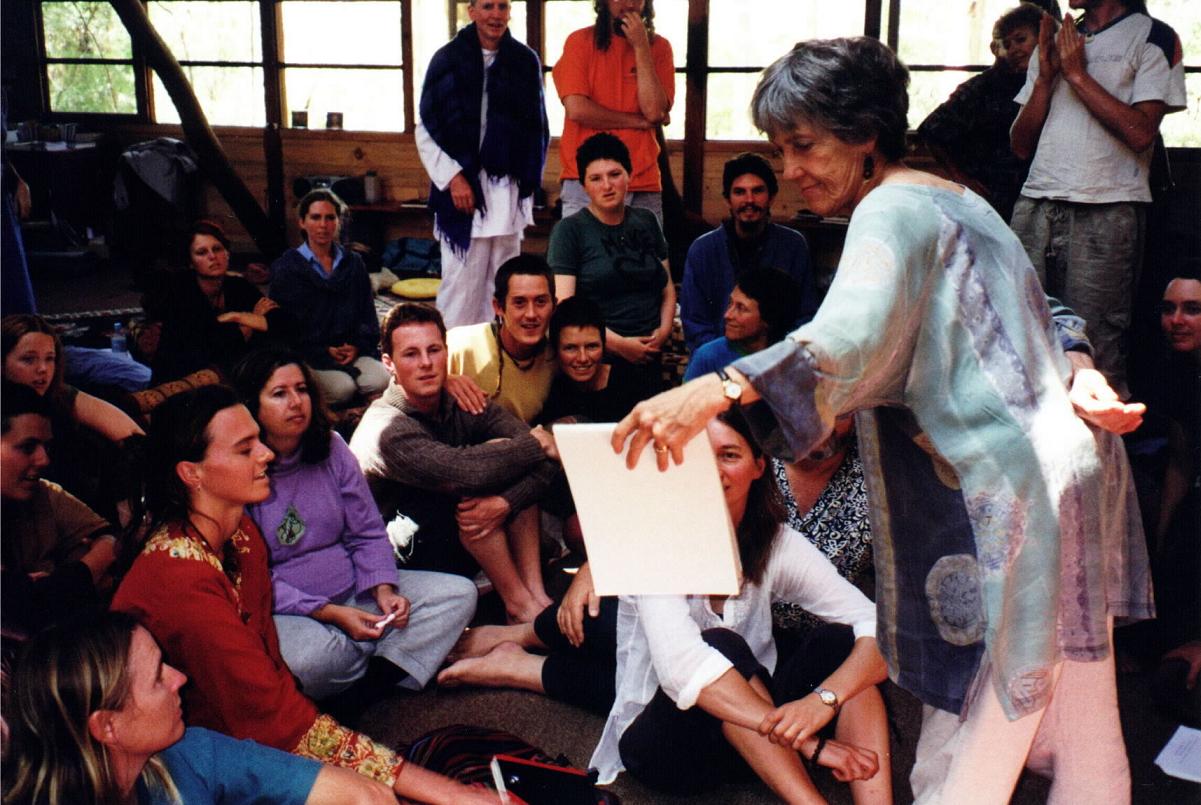

I think often what it takes is to recognize that under the surface of life as usual – under the appearance of success – people are in grief. There is grief for our world within people, and fear, and dread, and outrage at what is happening to our shared life and to the prospects for the future. What has encouraged me to even go into this work at all is realizing and then speaking to this capacity of people to suffer with their world. Most of my work is not standing at podiums talking to people, but leading workshops where we have structures for spontaneous expression, and people have a safe place to speak out [about] what they really feel and really think. This is evidence of the profound interconnectedness of all life, and evidence that they are really capable of suffering with their world, and this is the literal meaning of compassion. In every major religious and spiritual tradition, this ability is prized because it shows how interconnected we are, and from that source you can derive strength to act of behalf of the whole. Once people touch into their pain and don’t try to get rid of it, but bow to it instead, it breaks the spell; it breaks the industrial growth trance that most of us are trapped in.

Tell me a little bit about systems theory, and how it informs your teachings.

Well, it’s an absolutely exquisite way of seeing the world – it’s a set of conceptualizations deriving from the life sciences in the mid-20th century, and it shows how you can look at the world and see how life self-organized. You can take a bunch of hydrogen atoms and eventually get intelligence. This growth, internally generated, derives from our interconnectedness, and it helps me see that of course we are in grief for our world because we are like nerve cells within a greater body, and when that body is in trauma we are feeling that pain too. This realization has helped me to honor our capacity to suffer with our world. I see how that takes us by the hand and pulls us right into our power to act. Deep ecology is the same thing. My work is very much influenced by systems theory, and also by Buddhist thought.

In addition to your work in this field, you’ve translated the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke from the German. When my father was dying last year, I read aloud to him from Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, which has always been one of my favorite written works. What is it about Rilke’s writing that is so essential to the human experience?

That has been one of the great joys of my life, translating Rilke. Along with my friend Anita Barrows, I’ve edited Rilke’s Book of Hours and the book called In Praise of Mortality. I’ve got so nowadays I don’t give a talk without reading some poetry, because at the end of an era you need fresh ways of using words, and poetry conveys so much more to people than expository words. I will be teaching through poetry as well as argument.

When I started doing group work around the future beings and deep time, I remember I read one of those letters in Letters to a Young Poet, one that was written around Christmas 1923, about the future ones entering your life like they enter a house, and how it’s never the same. And that description was so similar to what happened to me and my colleagues when we allowed the future beings to be real to us.

4•1•1:

Joanna Macy will speak at the Lobero Theatre on Monday, October 29 at 7:30pm as part of the Santa Barbara City College Continuing Education lecture series, Mind & Supermind. For tickets, call 687-0812 or visit lobero.com.