From Birth to Victory, The Saga of a Santa Ynez Valley Racehorse

Gentle Romeo Rising

It was a starry night in the Santa Ynez Valley when the racehorse to be named Gentle Romeo came into the world. He was born at 10:20 p.m. on April 5, 2004. He was the fifth foal and the first colt delivered by Quiet Romance, a beloved broodmare at the River Edge Farm near Buellton.

Gentle Romeo was one of 37,822 North American thoroughbred foals registered in 2004 by the Jockey Club. Although most were bred for the purpose of racing, the odds were against them from the start. According to statistical expectations, fewer than half would make it to a starting gate, and just one in 10 would ever win a race. A single horse with a mystical combination of ability and luck would win the Kentucky Derby in 2007.

Two factors were in favor of the Quiet Romance colt’s chances at least to have a day at the races: his breeding and his upbringing. His sire, Benchmark, was gaining a reputation as one of California’s top stallions. Quiet Romance had earlier produced two fillies, Silent Sighs and Proposed, both sired by Benchmark, that would become stakes winners. Their newborn brother would be raised in the same environment that prepared them for the bugle’s call at Santa Anita, Hollywood Park, Del Mar, and other racetracks.

Along the River Edge

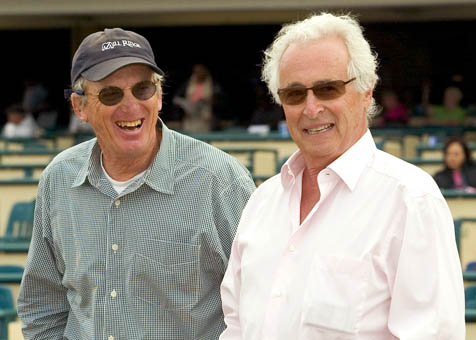

River Edge is a 240-acre complex of stables and tree-lined pastures that spreads on both sides of Highway 246. It grew out of a tomato patch that New York entrepreneur Marty Wygod purchased in 1976 to house his own thoroughbred-breeding operation. Wygod hired Russell Drake, a horseman who had migrated from New Mexico to California, as his farm manager. The partnership of both men, now in their mid sixties, is still going strong.

“New Mexicans and New Yorkers normally don’t get along,” Drake acknowledged. But in this case, it is a symbiotic relationship.

Wygod lives in a world of high finance. He developed a mail-order pharmaceutical company that was sold to Merck & Co. for $6.5 billion in 1993. His growing prosperity enabled him to invest heavily in horse racing, a sport that had enthralled him as a young man. His wife, Pam, oversees philanthropic projects. The couple moved from New Jersey to California in 1995 and reside on an estate in Rancho Santa Fe.

For more than 30 years, Drake has spent the majority of his waking hours at River Edge. “The farm is more his than mine,” Wygod said. Drake dons a billed cap every morning and oversees the care and feeding of several hundred horses. The population consists of stallions, mares, foals, yearlings, and layovers (horses taking a break from racing and training). Not all are owned by the Wygods. Other owners send their mares to breed at the farm.

Drake has a keen eye for the conformation of horses, and Wygod consults with him before matching his mares with stallions. “Russell is my main consigliore for breeding,” Wygod said. When a successful racehorse is produced, Drake gets the satisfaction of an artist. But he seldom goes to the races. The Wygods get to bask in the glory and reap the monetary rewards of his toil.

Wygod owns more than 70 broodmares. He breeds some of them in Kentucky, home of the richest pedigrees. It cost Wygod $500,000 to pair his prized mare Tranquility Lake with the legendary stallion Storm Cat. They produced a colt the Wygods auctioned off at the 2005 Keeneland yearling sales. A buyer paid $9.7 million on behalf of Sheikh Mohammed of Dubai for the colt, which has so far raced with only modest results in England. “Marty’s the luckiest guy I know,” Drake said.

The breeding scene in California is not as high-toned as Kentucky’s. There are three stallions standing at River Edge Farm. Bertrando, the oldest at 19, is one of the state’s leading sires. His progeny led all others in 2007 earnings ($4,235,168). He commands a stud fee of $12,500. The farm also stands 17-year-old Benchmark ($10,000 fee) and 12-year-old Tribal Rule ($5,000). The three stallions have seen 68 percent of their foals become runners. They fathered a total of 185 foals in the 2004 crop.

Wygod purchased Benchmark, a son of Alydar, for $475,000 as a weanling in 1991. He was a late bloomer on the track, winning four races at age six. He was retired to stud in 1999, and there was initially no fee for his services. When his first crop started running and winning races, his reputation grew, and now he ranks among the top 10 California sires.

Quiet Romance is a daughter of Bertrando, so when she was bred to Benchmark, it brought together some of the best racing genes California has to offer. But there were no guarantees when that colt was born almost four years ago.

Spring 2004

Most horses are born at night. “The mothers like it quiet and peaceful,” Drake said. When the time is near, “they start to get nervous and pacing. They might drip a little milk.” Farmhands keep an eye on them. “The mares with experience lie down,” Drake said. “Very seldom do you have to assist them. The babies come out with their noses between their legs. But it doesn’t always work out that way.”

In a very short time, the newborns are on their feet and begin nursing. They will be with their mothers the next six months. A few days after his birth, Quiet Romance’s colt was frolicking outside his stall. On matchstick legs, he ran counter-clockwise around his mother, a big and sturdy dark brown mare.

The colt’s birth weight was around 75 pounds. “He’s a piddly looking little fellow now,” Drake said. “He’ll be gorgeous when he gets older.” His coat was dark brown, and he had a white star on his forehead.

Quiet Romance, a mare with dreamy eyes and a sweet disposition, was a looming presence in the center of her baby’s orbit. “Most mares are protective of their foals,” Drake said. “She teaches him manners. She nips, pushes him, gives him a look. Certain signs keep them paying attention.”

Nearby was a reminder that things can go tragically wrong. Pirate’s Glow, a retired mare, was in a pasture watching over two foals who were orphaned at birth. One of the dams suffered a fatal uterine rupture. “The owners live for the races,” Drake said. “They don’t experience the everyday stuff-the getting up in the middle of the night, the heartbreaks, the dying. Nobody likes to hear bad things.”

The foaling season from January to May is the busiest time on the farm. More than 150 horses would be born at River Edge this year. Breeding for the next year’s crop also takes place during this time. The gestation period is 11 months. Quiet Romance would be empty in 2005, but then she would be bred to Benchmark for the sixth time. In 2006, she would be sent to Kentucky and bred to Giant’s Causeway, another high-priced stallion.

At River Edge, the Cal-breds are treated with no less respect than their gilded Kentucky cousins. The paramount concern for the young colts and fillies is to protect them from disease. Within 24 hours of his birth, the Quiet Romance colt received a $250 dose of plasma to boost his immunities. He received another dose after three weeks.

Veterinary technician Carrie Drake (no relation to Russell Drake) kept a close watch on the new crop of foals. She was worried about the approach of a dry, dusty summer, when the bacteria that cause equine pneumonia would be rampant. The population boom on the farm was another concern. “We’ve got foals up the wazoo,” she said. “When it starts looking like a feed lot, that’s not good.”

One foal became badly infected during the summer and was euthanized. “We lost the battle,” Carrie said. But they might win the war. “We harvested the bacteria and sent it to the firm that makes our hyper-immune plasma,” she said. “That foal’s death may make a plasma that protects against the bacterial mutations on our farm.”

Autumn 2004

The “piddly looking little fellow” was now a small horse weighing 500-600 pounds. It was time for the foals to be separated from their dams. “Weaning is very stressful,” Carrie said. “They nicker, they scream. Some of the mares are anxious, but some couldn’t care less.”

The young horses got a taste of discipline after weaning. They were put in the barn, groomed, and led around by handlers. They practiced loading and unloading in vans. “We give them two weeks of that treatment and then turn them out to become wild again,” Russell said. “It really helps later on.”

After being turned out, the Quiet Romance colt shared a corral with one of his peers that was sired by Bertrando. His mother was Feverish, a high-strung mare that had won 12 times during her racing career. (Quiet Romance had gone to the breeding shed without being raced.)

For the next several months, the two colts would eat, grow, and play together. But there was a downside. “Colts are like high-school kids,” explained Russell. “They want to get down on their knees and fight each other. Sometimes they get hurt.” Nonetheless, he confirmed, “They’re doing pretty good. There’s nothing that indicates they’re heading in the wrong direction. Sometimes it doesn’t always turn out well. All of them are not meant to be perfect. That’s the way nature is.”

In mid October, a state-certified thoroughbred identifier visited the farm to start the Jockey Club’s registration process for potential racehorses. She took four photos of each newborn and recorded its distinguishing characteristics. “It’s a very important part of the integrity of the business,” Russell said. “You want to be sure you’re selling the right horse at the sales. You don’t want horses to be mixed up when they go into training. It’s not about people being dishonest, but a matter of avoiding mistakes.”

DNA samples are taken to confirm the horses’ parentage. River Edge has had one case in 30 years, Russell said, where two foals were inadvertently switched after birth.

Spring 2005

All the foals born in 2004 officially became one year old on January 1. It is a convention that puts horses in the same age groups for racing. They would not race until they were at least two years old. At 800-900 pounds, the yearlings were about three-quarters the size they would eventually attain.

“They’re just about getting their balance,” Drake said. “They go through awkward stages. : It’s like gangly kids becoming young men.”

The Quiet Romance colt was alone in its corral. Drake had moved the Feverish colt to a separate pen. “It’s more for me than for them,” the farm manager said. “I don’t know if that’s the best way to raise a competitive racehorse, but I don’t want to see them get hurt. They start getting rambunctious when the weather warms up. I sleep better at night knowing their tendons aren’t in harm’s way.”

It had been a wet, muddy winter, and the colts were shaggy and dirty. “Sometimes young horses like to be little pigs,” Drake said. “They’re going to be slick and shiny in another month or two.”

Marty and Pam Wygod went through the ups and downs of horse racing in April with their three-year-old filly, Sweet Catomine. Another offspring of Storm Cat, she went into the Santa Anita Derby as the favorite and was touted as a rare filly who might win the Kentucky Derby. “She’s such a beautiful, big, strong horse,” said Drake, who visits Kentucky every year to evaluate the Wygods’ stock. “You can’t help getting goofy over them, wishing and anticipating what they can do.”

But after winning four of her first five races, including a dominating performance at the Breeders’ Cup in the fall, Sweet Catomine finished fifth at Santa Anita. Marty decided to retire her for breeding. Giacomo, the colt who came in fourth at Santa Anita-just ahead of Sweet Catomine-went on to win the Kentucky Derby as a 50-1 long shot.

Autumn 2005

With the yearling sales in Pomona coming up, Drake had to decide which horses to keep from the 2004 foal crop. “Eighty of them are ours,” he said. “I try to cut them back to around 30.” The Quiet Romance colt was among the keepers.

Drake had bad news about the Feverish foal. He had seemed “a little off” when he was separated from his fellow colt, and in the days following, his coordination deteriorated. It turned out he had serious spinal damage, and he was euthanized.

“They’re called wobblers,” Drake said. “Other than a horse with a broken leg you can’t fix, that’s the worst nightmare. It makes me sick. Sometimes they fall and can’t get up. If they can’t get up or down, eat, drink, and exercise, sometimes the humane thing to do is put them down. I’ve never seen one recover. It’s a shame. That colt had a nice conformation. It looked like he’d be a real good athlete.”

The Quiet Romance colt was healthy and robust. He had ample room to roam in his corral. There was a furrow along the fence where he was running back and forth, often racing parallel to another yearling in an adjacent corral.

Spring 2006

The colt finally had a name, Gentle Romeo. “My wife picked it out,” Marty said. “It goes with the family of Quiet Romance.” The colt also had a new home, the San Luis Rey Downs Thoroughbred Training Center in San Diego County. He was transported there in late January to start learning how to race.

“They’re like 30 kids running around,” said Byron Hendricks, a self-described “beach cowboy” who had been training horses at the center for 25 years. He starts them out with a lot of human contact, puts a pad and saddle on them in the stall, then a rider sits on them. When fully broken, they hit the one-mile training track.

“It’s a long road,” Hendricks said. “Their bones are still growing. Exercise builds bone density. As the year goes on, they get seasoned. I don’t get attached to them. I know they’ll be leaving.”

Byron’s cousin, Dan Hendricks, is a racetrack trainer based at Santa Anita. He was making news as the trainer of Brother Derek, who emerged as one of the top three-year-olds of 2006. Brother Derek had been sired by Benchmark and purchased by Dan Hendricks on behalf of owner Cecil Peacock. The colt won the Santa Anita Derby and went east as one of the favorites in the Kentucky Derby. He would try to be the first Cal-bred horse to win the race since 1962.

Everybody at River Edge was pulling for Benchmark’s son. Drake had a special friendship with Dan Hendricks, who continued working as a trainer after he was paralyzed from the waist down in a motocross accident. “My heart’s with Danny and Brother Derek,” Drake said. “I’ve got to stay here at the farm and try to make more Brother Dereks.”

Barbaro won the Kentucky Derby in stunning fashion. Brother Derek had to start in the 18th post position and gamely finished fourth. He also took fourth in the Preakness, the fateful race in which Barbaro’s leg was shattered, followed by the seven-month battle to save his life.

Autumn 2006

Gentle Romeo came to Hollywood Park like a small-town kid starting his freshman year at a large university. He took up residence in the barn of John Shirreffs, a veteran trainer who had prepped Giacomo for his upset win at Churchill Downs.

“The new horses aren’t used to the traffic- all the other horses working, galloping, running up behind them,” Shirreffs said. “You have to teach them not to react to every sound.”

Gentle Romeo was proving to be “a very difficult horse,” Marty said. “He’s the opposite of his name”-the “gentle” part, anyway. “He’s a handful,” Shirreffs said. “We had to build a higher stall. He used to rear up and get his feet over the top.”

But he was very much a Romeo. “I could never have a filly in the stall next to him,” Shirreffs said. “He’d run through a wall for a filly.”

The trainer was in no rush to send Gentle Romeo out to his first race. “He had a little bit of a shin problem at the training center,” Shirreffs said. His workload would be increased gradually. “The stress level at the track is much different from the farm. Horses internalize everything. They can’t talk to us. Their relation to the world is physical. You have to watch how they’re eating. The digestive system is tied to their emotions.”

Spring 2007

At a cost of $600 before the January 21 deadline, Gentle Romeo was one of 450 early nominees for the Triple Crown of 2007. Sixteen of them were from California. But it became apparent he would not be mature enough to start racing before the Kentucky Derby on the first Saturday in May. The winner of the Derby was Street Sense, who had been the champion two-year-old of 2006. By the end of the year, Street Sense would be retired to the breeding farm, with a stud fee of $75,000.

Summer 2007

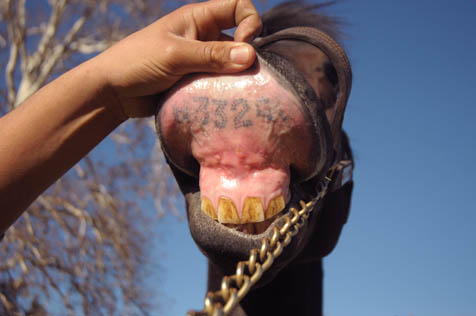

Gentle Romeo, with the Jockey Club’s serial number tattooed under his upper lip as a seal of approval, made his debut in the fourth race at Hollywood Park on July 7. He was one of eight entries in a special weight race for maiden thoroughbreds, three-year-olds and older, with a purse of $61,200. The distance was 6½ furlongs. Gentle Romeo went off as the second choice of the bettors at odds of 2½-1.

Shirreffs decided to put blinkers on the colt. “They help keep the horse focused, not thinking about everything going on around him,” the trainer said. “Maybe 15 percent of horses need blinkers.”

Richard Migliore was his jockey. “He’s not only a jockey but a horseman,” Shirreffs said. “He understands what a horse needs, when to back off, when to be aggressive.”

According to the official race notes: “Gentle Romeo broke a bit slowly, settled off the rail, advanced outside on the turn and four wide into the stretch, and proved best under some urging and steady handling late.” He won by 2¾ lengths over Dr. Skimming and claimed winner’s earnings of $36,000.

On August 15, Shirreffs put Gentle Romeo into a $65,000 race at Hollywood Park over a distance of 1¹/16 miles “He had a nice stride and I thought he could handle the distance,” he said. Gentle Romeo went off as the favorite but never fired, finishing sixth in a field of 10. The winner, Rush with Thunder, was one of the River Edge Farm’s yearlings that were sold in fall 2005. He was sired by Tribal Rule out of the mare Gentle Words.

Autumn 2007

Gentle Romeo dropped down to a seven-furlong race at the Hollywood Park fall meeting the night of November 9, and he made it 2-3 by rallying to beat the favorite, River Echo, by a half length. Joseph Talamo, a promising young jockey, was the rider this time. “He worked with the horse early on and asked if he could ride him,” Shirreffs said. With the victory, Gentle Romeo banked $27,000.

After the race, Gentle Romeo’s shin on his right foreleg started bothering him. Upon examination, a fine stress fracture was detected. Sparing no expense, Marty had the highly regarded equine surgeon Wayne McIlwraith tighten the crack with a screw. “The horse was standing during the operation,” Marty said. “The vet assured me he’ll be back.”

Today

Sent back to River Edge Farm to recover from his injury, Gentle Romeo received another whammy: the removal of his Romeo nuggets. It had been decided to make him a gelding. It would preclude his ever becoming a stud but was expected to benefit his racing career. The procedure was performed in late December.

“Now he’ll be able to keep his mind on business,” Drake said. “He was getting too excitable. All he was thinking about was females. Geldings have been fabulous racehorses, and they keep going for a long time. John Henry and The Tin Man-they didn’t worry about who they were going to bed with.” Shirreffs said, “It wasn’t my decision, but I’m glad they did it. It will be easier for the horse when he gets back into training.”

Gentle Romeo’s injured leg influenced the decision, Drake said. “It’s nicer to have them be quiet if they have a little fracture that needs healing. He used to be kicking the walls. Cutting takes it out of them.”

And so the story of this horse is to be continued. It is a story fraught with risks and calculations. It is a story that touches on the rich complexity of one of the world’s oldest, most uplifting, and most daunting sports.