The Future of Biofuels Takes Root in S.B.

Growing Gold

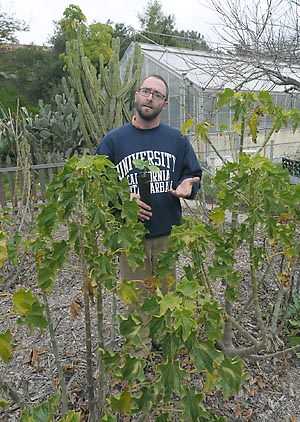

At first sight, it looks like a weed-a ragged shrub bearing sickly green fruit, growing across a plot of wasteland near the dump that overlooks Highway 101. It grows on almost any soil, and with hardly any rain. Its seeds are as toxic as any poison. But this unusual plant conceals an unlikely secret: The oil from its thick black seeds can be used to power your car. And this hardscrabble patch here in Santa Barbara is a project on the cutting edge of one of the fastest-growing industries in the world.

The plant is Jatropha curcas-also known as the Barbados nut or Physic nut, and originally brought to India from South America by Portuguese sailors centuries ago for use as a “living fence” that animals and insects instinctually avoid. Indian farmers soon found that the thick oil that came from crushed jatropha seeds could fuel their lamps. But it wasn’t until very recently that researchers found the same oil could also make diesel fuel. Since, jatropha has been the rising star of the biofuels boom in countries like India, where farmers are planting thousands of acres with this weed. In June, oil giant British Petroleum announced a joint venture to invest $160 million in jatropha. And in September, investment firm Goldman Sachs reported that biodiesel from jatropha could cost just $43 a barrel to produce-far less than corn ethanol or crude oil. But, in spite of all the interest, jatropha has never before been cultivated in the United States. That is, not until now.

Growing Fuel

For a relatively young industry like biofuels, Santa Barbara resident Russell Teall has more experience than most: He’s been working with biofuels now for 14 years. A UCSB grad, he’d long been interested in environmental causes, but when he first became involved in biofuels it was partly by chance. “I had read an article in a trade publication about a guy who had gone around the world in an inflatable boat powered by biodiesel, and called an 800 number to find out more about biodiesel. They ended up hiring me to do some consulting work for them,” Teall said. A consulting stint with the National Biodiesel Board led to other things. Started in 1999, Teall’s company, Biodiesel Industries, has become a pioneering innovator in the field. He can quietly reel off a jaw-dropping list of accomplishments: a plant in Australia recycling cooking oil; a project in Detroit with DaimlerChrysler; a joint venture in Mysore, India; a million-gallon-a-year plant built for the Navy at Port Hueneme; and a plant in Denton, Texas, powered by landfill gas, that won an Environmental Protection Agency award in 2005.

El Sueno Road. The spot isn't suitable for many crops, but jatropha just happens to thrive in so-so soil, even without the amount of fertilizer many other biofuels sources might require.

Not only does Teall manufacture biodiesel, he burns it as well; he powers his truck on biodiesel much of the time. “We’ll use diesel sometimes if we’re going a long distance,” he said. In the drink carrier, he keeps a glass jar full of a golden liquid slightly thicker than water, a sample he wants to test. It’s biodiesel, the elixir that many in the industry claim has the power to set us free from our dependence on fossil fuel. Teall believes there are any number of advantages to biodiesel, not just over diesel but even over other bioÂ-fuels like ethanol. “For every unit of energy you put in, you get 3.2 units of energy out. With ethanol, generally it’s considered good if you can break even on your energy balance,” Teall said. Biodiesel can be made from most common vegetable oils or even waste cooking oil. The energy gain results both from the ease of conversion and from the source; crops like castor seeds or jatropha are oil-rich, and their oils are high-energy.

Biodiesel may not only have a better energy balance than some of its competitors, but it could be more practical to use as well. In warm-weather areas, most newer cars or trucks that burn diesel fuel require no conversion. “It’s kind of like the plug-and-play version of alternative fuels,” Teall said. Advantages like these are among the reasons that both the trash collection service and the City of Santa Barbara vehicles already use B20-a 20 percent biodiesel blend-in their vehicles.

But if biodiesel has many benefits, it’s not without problems as well: Using food crops for fuel can have unpleasant consequences. A 2006 National Academy of Sciences study estimated that turning all U.S. soybean production to biodiesel would replace just 6 percent of diesel demand and push food prices sky-high. Especially for developing countries, trading food for fuel just isn’t an option. Here, then, is where jatropha may offer a solution. While estimates vary, jatropha is believed to have higher oil yields than other common feedstock crops like soy: The seeds have anywhere from 30-50 percent oil content depending on growing conditions. Even more importantly, jatropha is a tough, drought-resistant plant, able to grow in wasteland and without fertilizer and therefore need not compete with food crops for land. Unknowns loom-not least because jatropha has never been cultivated on a large scale before-but its higher yield and lower input combine to make jatropha an attractive possibility.

Teall was already familiar with jatropha thanks to Biodiesel Industries’ work on a study in India with the U.S. Agency for International Development, so in 2006, in partnership with Growing Solutions, a Santa Barbara County not-for-profit, Teall imported jatropha seeds under a USDA permit to grow on two test plots here in S.B., one at Santa Barbara High School and the other on a plot next to a Growing Solutions nursery at the dump. But all this, he said, is just the start; he plans to plant 10-15 acres in Santa Barbara County soon. “We’re going to start doing more acreage this spring,” he said. “Right now we’ve got 250 plants. The next step would be to do 5,000-10,000 plants. There’s about 800 or 700 plants per acre, so basically a 10-15 acre plot.” Teall said he believes that jatropha could eventually become part of an energy-independent Santa Barbara. “There’s a lot more study that has to be done, and gradually developing hardier varieties, and we’ll eventually be able to have a reliable commercial crop that can be grown in dry land,” he said. “We’re never going to replace strawberries, [which] generate $35,000 an acre, so land that’s suitable for strawberries should be growing strawberries on it. But there’s a lot of ranch land, dry ranch land, that could be suitable for this kind of a crop,” Teall said. “And there’s more than enough land if you have the right variety of jatropha to supply 100 percent of the diesel needs in Santa Barbara County.”

Soil to Oil

Growing jatropha in Santa Barbara may hold tremendous potential, but getting started wasn’t easy-and it was here that Teall sought assistance from Growing Solutions, of whose board he is a member. The project was in some respects a first for Growing Solutions, but in others a complement to its conservation work. “We generally work on restoring native habitats; that’s our primary focus,” said Karen Flagg, cofounder of Growing Solutions. “Jatropha is a bit of an expansion on that because we would like to see native habitat not destroyed, and jatropha doesn’t need prime land. The great thing about it is it can grow on disturbed soils.”

Growing Solutions in turn enlisted the aid of the Green Academy, a program it helped found at Santa Barbara High School that’s run by science teacher Jose Caballero. Now five years old, the academy provides hands-on experience in horticulture-tending plants in an on-campus organic garden. For the Green Academy, then, the jatropha project was a natural extension of existing work. Growing jatropha would, Caballero said, offer his students a chance to take part in a one-of-a-kind experience-introducing a foreign plant species to California and watching it progress. “For the students, that data collection and that experimental design part-figuring out how to cultivate it best-is interesting science,” he said.

But all this is only the beginning, Caballero said, for what may be an even more ambitious project starting this year or next. “We’re looking at doing the full biodiesel lifecycle in high school. So we’re hoping to go from jatropha seeds to a modified vehicle running on biodiesel all at the high school. Technically any diesel car can run on biodiesel, so we’re hoping to have different branches of the high school, a program that covers the cultivation of the plant, the chemistry and physics of catalyzing the oil into biodiesel, and then the mechanics of the different options for the cars. It’s entirely possible that’ll be running at the school within a year. It’s just a matter of funding.”

Just as much as funding, the program depends on the jatropha plant’s success in the Southern California climate, and here the results have been positive, with one lethal exception so far-unexpected hard frosts. A subtropical plant, jatropha will tolerate almost any conditions except freezing cold. “We had the coldest winter in 30 years last winter and we had five consecutive nights of freezing weather, so we had about a 40 percent mortality in the jatropha grove,” Teall said. As he points out, however, the short-lived damage is actually helpful in the long run. The jatropha plants that survived the frost are the most cold-hardy of the lot, and so over time, in a process similar to natural selection, the remaining plants become increasingly resilient.

Caballero and his students are even more optimistic about jatropha’s success in the Santa Barbara climate. “Light frost seems to be something we can work around; it’s a little extra hassle but the plants will be fine. : And plant size has shown to be a factor in how serious a heavy frost is. We’re finding that larger, older plants are quicker to recover from a hard frost. Aside from that, our climate’s perfect.”

Fossil Free by ’33?

As the jatropha project expands from hundreds of plants to thousands, it might become commercially viable as a local fuel source. The prospect of fuel from local supply is one that many, among them the Community Environmental Council (CEC), believe is vital to Santa Barbara’s future. The CEC refers to its own initiative as the Fossil Free by ’33 campaign. “Our program is to do what we can as a nonprofit to transfer away from fossil fuels,” said Tam Hunt, CEC’s energy program director. “So, basically, looking in detail at what the county can do to get off fossil fuels-and that means all fossil fuels.”

The need for an alternative is all but undeniable. According to a February 2007 U.S. Government Accountability Office report, most experts believe that world oil production will peak by 2040 at the latest, meaning that oil prices are set for a dramatic rise. As economic pressures and increased public concern about long-term climate change coincide, this may be an opportune time for promoting alternative fuels to the public-although to Hunt and the CEC, it’s important that Santa Barbara use local sources. “Because of the concerns about ethanol and energy inputs, we want to focus on local feedstocks. There are four that we’re looking at-recycled cooking oil, jatropha, algae (which is more of a long-term proposition), and soy as a backup,” Hunt said. Between these and other renewable energy sources, Hunt, like Teall, said he believes it’s entirely possible that Santa Barbara can become completely energy independent-a self-sustaining city-although he admits it won’t be easy. “This kind of change is a huge project, involving significant changes in infrastructure,” he said. As one means to that end, the CEC is working with Teall to find the best site for his planned jatropha planting later this spring, with hopes of more to follow.

It’s an ambitious vision, no doubt-a Santa Barbara reliant on its own energy and a world powered in part by oil from a poisonous weed. Questions about just how to achieve the vision of energy independence abound. For now, at least, the golden promise of the future is here, in a gangly shrub a few feet tall, buffeted by the wind from the highway, and the oily black seeds concealed in its pale green fruit.