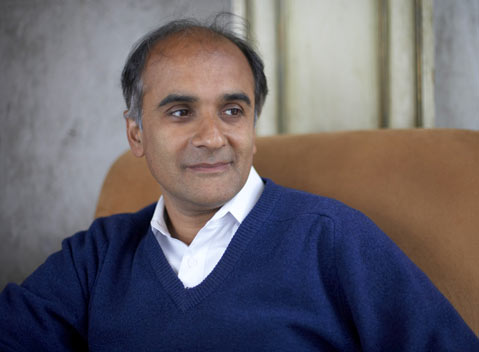

Pico Iyer’s New Book The Open Road Distills the Dalai Lama’s Teachings

The Opportunity of Loss

On June 27, 1990, when the Painted Cave Fire swept down from the Santa Barbara foothills, Pico Iyer’s family home went up in smoke.

“I was stuck in the middle of the fire for three hours, surrounded by 70-foot flames, and saved only by a Good Samaritan who had driven his water truck up into the conflagration,” the celebrated writer told me recently. “I lost about eight years’ worth of books I was working on and 15 years’ worth of notes. That evening, I went to Vons on Chapala to buy a toothbrush, and that toothbrush was all I owned in the world, really, when I went to sleep that night.”

For Iyer, losing his house was a tiny taste of exile. But he also saw it as an opportunity to distinguish what was most important in life. “I woke up the next morning and thought: Either I can mourn the fact that I have lost my past, and my future, and everything I thought defined me in the world, or I can choose to say, well, actually, this is a liberation. I’ve always told myself that I want to live more simply and without so fixed a sense of home and without possessions-now I have a chance to live up to this bold claim.”

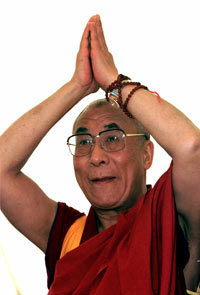

The idea of loss as an opportunity for growth is at the heart of Iyer’s latest book, The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. The book is a culmination of more than 30 years of conversation with Tenzin Gyatso, otherwise known as His Holiness the Dalai Lama, leader of the Tibetan people and exile from his homeland.

Any book on Tibet is of particular interest at the moment in light of the recent uprisings in Lhasa and the upcoming Olympic games in Beijing. But The Open Road is really much more than a journalist’s account of 30 years spent in the presence of the Dalai Lama and in conversation with Tibetans living in exile in Dharamsala. What makes this book unique is the way in which Iyer, a non-Buddhist, presents the Dalai Lama’s teachings as the Tibetan leader himself might, distilling a vast and complicated topic into a universal lesson that’s accessible and relevant to all of us. And it’s Santa Barbara’s turn to listen on Monday, May 19, when Iyer comes to UCSB’s Campbell Hall to discuss the book.

Exile as Opportunity

Born to Indian parents in England and raised there until the age of seven, Iyer grew up listening to his father’s stories of the Dalai Lama’s plight, and recounts his childlike interpretation: “good Tibetans, bad Chinese.” It was his father who, in 1974, took him to Dharamsala and introduced him to the Dalai Lama.

Iyer was 17 at the time, and reluctant to show any enthusiasm for this colleague of his father’s. Yet something made a deep impression on him as he sat with the exiled leader high in the mountains of northern India where the Dalai Lama had set up residence in 1959, having fled Tibet after a failed uprising against Chinese troops. Speaking to me earlier this month from his Portland, Oregon, hotel room while on tour for his new book, Iyer explained what he’d realized long ago.

“He’s the rare person,” Iyer said, “who sees exile not as a loss, but as a possibility.” As a journalist, Iyer would go on to report on many of the world’s most troubled regions, from Beirut to Cambodia to El Salvador, and something of the Dalai Lama’s example would remain with him, filtering into his personal life and into his writing.

Thus began Iyer’s ongoing relationship with the Dalai Lama. As he watched, the spiritual and temporal leader of the Tibetan people transformed himself into a global figure, traveling far beyond the borders of his community in exile to rally support for Tibet and to share his lesson with anyone who cared to hear it. Exile as an opportunity was far more than an abstract concept; this man who had been born in one of the most remote and isolated corners of the world seized at the chance he had been given to bring his nation and its struggles to the forefront of international consciousness.

Throughout the years, Iyer accompanied the Dalai Lama as he met with heads of state in Europe and America, delivered speeches to crowds of thousands in Canadian sports arenas, and meditated with Buddhist monks in Japan. Especially when he spoke to Westerners, Iyer noticed, the Dalai Lama distilled the core lessons of Buddhism down to very simple, universal teachings: the importance of treating all people well regardless of their status, the significance of good deeds no matter how small they might seem, the value of nonviolence.

In The Open Road, Iyer draws analogies between the Dalai Lama and a doctor whose aim is to heal infirmities. “One of the things that the Dalai Lama has done so well,” Iyer said, “is to take this very intricate and specific body of knowledge-Tibetan Buddhism-and when he comes, say, to California, to distill that knowledge into these very everyday, human, universal tablets, like a medical prescription that he’s handing out that any of us might be able to use and benefit from.”

A Difficult Lesson

Unsurprisingly, these aren’t always the lessons the Dalai Lama’s listeners want to hear.

Iyer captures the conundrum of the Tibetan leader’s position: either worshipped as a god or dismissed as a simpleton by many in the West, vilified by the Chinese government for his perceived revolutionary tendencies, and urged by many of his own people to take a stronger stand against China.

The recent riots in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa have brought into high relief the frustration of the Tibetan people at the ongoing Chinese occupation of Tibet and at what they see as the Dalai Lama’s passivity. Rather than condoning violence, the Dalai Lama encourages patience, refers to the Chinese people as Tibet’s “brothers and sisters,” and calls for open dialogue.

His model may be an inspiration to the world, but for many Tibetans, the Dalai Lama’s “universal lesson” is a painful one to learn. In The Open Road, Iyer describes a conversation with the vice president of the Tibetan Youth Congress-the spokesperson for the more restless, militant young Tibetans-who suggests that the Dalai Lama’s compassionate, farsighted approaches are good ideas in theory, but that Tibet doesn’t necessarily want to be the guinea pig for the experiment of world peace.

“Every Tibetan I’ve met, in Tibet or outside Tibet, is unswervingly devoted to the Dalai Lama,” Iyer explained, “but what they sometimes say is, ‘His Holiness starts his day every day by praying for the Chinese, but we’re not up to that. Maybe 10 or 1,000 incarnations from now we will be.'”

Without negating the Tibetan people’s struggle for freedom and their anguish at seeing their culture suppressed and destroyed, Iyer places the Dalai Lama in a larger, global context, likening his lesson for the world to that of other peace leaders like Czechoslovakia’s V¡clav Havel or South Africa’s Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

“V¡clav Havel woke up one day in prison, and eight weeks later he was unanimously elected president of Czechoslovakia,” Iyer pointed out. “Desmond Tutu woke up one day under the shadow of apartheid and the next day, so to speak, that was gone. So I think as a leader for 67 years now, who has seen everything happen across the globe and has followed it very, very keenly, the Dalai Lama is aware of this constant flux. That’s one reason why he doesn’t compromise, and doesn’t capitulate, and doesn’t endorse violent action now: Who knows what’s going to happen six months from now, and what that violent action might jeopardize?”

In his own life, Iyer has noticed these lessons taking hold in ways that transform his reactions to loss and to conflict in many situations-not only when his house burned to the ground. “It’s am azing how much this has helped me move through my world,” Iyer told me. “I’ve realized that there’s no need to imprison myself in polarities-that I could be a Democrat but I would never need to say anything bad against the Republicans; that I can care deeply about Tibet but I am not in a position to say anything bad about China.

“Or let’s say somebody writes a horrible review of this book of mine,” he continued. “Maybe 20 years ago I would have thought, ‘How could he do that? I worked so hard on it for five years, and he’s turned it into a travesty.’ But now I think I would figure that he’s in exactly the same position as me: He’s a journalist working hard to support his family and trying to give his readers an objective response to something, and in fact he’s doing exactly what I would do in the same situation.”

Gaining the World

No matter who we are, no matter the context of our lives, Iyer suggests, there is a lesson to be learned from the Dalai Lama’s example. Whether we’re facing a conflict with a family member or a colleague, a divorce from or the death of someone we love, imprisonment or torture, political persecution or literal exile, the same lesson applies: Every struggle is an opportunity for us to distinguish what is most important to us, “to sift,” as Iyer put it, “what is lasting and what is essential from what is really just part of the flow of impermanence.

“The world seems more divided than I’ve ever known it,” Iyer remarked, “and certainly our country seems more polarized than I’ve ever known it. So, I thought that this quietly radical, political, and global thinker who is trying to see things outside the usual divisions and polarities might be a liberating figure. I think he urges us toward a more inclusive view, and ultimately offers us freedom from divisions in our heads and in our politics.”

Even when our lives are reduced to ashes, Iyer suggests-maybe even especially then-we have a chance to redefine what it means to be alive, what it means to be home. In losing Tibet, Iyer reminds us, the Dalai Lama gained the world.

4•1•1

Pico Iyer will deliver a lecture, Seeing Things Differently: The Dalai Lama and Our Divided World, on Monday, May 19, at 8 p.m., at UCSB’s Campbell Hall. For tickets, call 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.ucsb.edu.