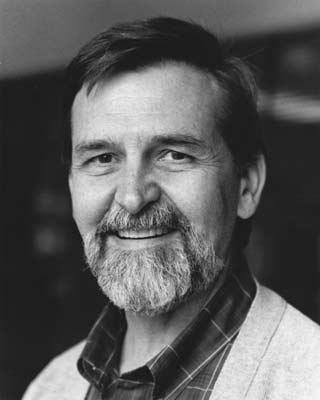

Richard Helgerson 1940-2008

UCSB lost one of its most distinguished humanities scholars with the death of Richard Helgerson on April 26 at the age of 67. To the campus and the English department, where he taught for 38 years, he was much more than the international reputation he enjoyed; he was a teacher and mentor of extraordinary generosity and a colleague whose wit and clear-sighted judgment were simply indispensable.

It was entirely characteristic of Richard that he would reject the common formula that he “lost” a “battle” with pancreatic cancer that was diagnosed the day after his 65th birthday. Aside from doubting the aptness of the military metaphor, he rather saw himself-as his daughter, Jessica Helgerson, suggested-entering into a “relationship” with something dark and strange, something that he knew would certainly end his life-and which, for that reason, he wanted to learn as much about as possible. And so, for the next two years and eight months, he was fascinated by, and spoke easily about, the progress of this “relationship.”

It was equally characteristic of Richard that the diagnosis didn’t stop him in his tracks. The previous month he had begun writing what he projected as a large comparative study of the “new poetry” of 16th-century Europe, one that he expected would take five or six years and carry him into a productive retirement. He had begun writing a chapter on Garcilaso de la Vega, a favorite 16th-century Spanish poet, then was arrested mid-sentence by the diagnosis on August 23, 2005. But he soon returned to work and recast the project as an extended essay on a single haunting sonnet the Spanish poet wrote on a military victory in Carthage-and his own “undoing” for love.

The result was an extraordinarily elegant short book, indeed as beautiful a piece of critical scholarship as one can imagine, in which Richard told in miniature the story of the “new poetry” that he had originally projected. Those of us who read the book in manuscript almost hesitated to tell him how good it was, thinking that if we could keep him working on it, he would, Scheherazade-like, cheat death as long as he continued telling his tale. But, in fact, the book needed no further work, and as it happened, through brilliant chemotherapy, Richard did cheat death long enough to see A Sonnet from Carthage: Garcilaso de la Vega and the New Poetry of 16th-Century Europe published last spring-to immediate favorable reviews.

In fact, the book was the capstone in Richard’s international reputation for a series of books devoted to the careers of Renaissance poets who created literary identities that were tied to emerging European nationhood. With a scholarship that was breathtakingly broad, he began with English Renaissance writers-Shakespeare, Spenser, Sidney, Milton-and extended his scope to French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian poets who participated in their own countries’ achievements of national identity. He was fascinated by the way generations of writers responded to the challenges of creating and recreating identities that hearkened back to ancient Rome but advanced their languages and nations to a prominence rivaling Rome’s. He began the story in Self-Crowned Laureates (1983) and continued it with Forms of Nationhood (1992), which won the prestigious James Russell Lowell prize of the Modern Language Association. Adulterous Alliances (2000) and an edition and translation of Joaquin Du Belay’s poetry (2006) followed.

Richard was also a gifted and challenging teacher, revered by dozens of English department grad students who found in him a mentor who would draw out their best work and prepare them for careers of teaching and scholarship across North America. His scholarly generosity knew no bounds, and he also seemed to know precisely the right question to ask of a student who needed direction. Richard taught his last graduate course in winter quarter, even though he knew the cancer was gaining on him.

His colleagues, too, benefited from Richard’s guidance. He and I came to UCSB the same year, 1970, and for years we read each other’s work and carried on a constant conversation about our scholarship-and much else. His shrewd advice never failed to illuminate a critical question for me, and I’m certain a good many of my colleagues could say exactly the same of Richard’s reading and critiques of their work. He was, moreover, thoroughly devoted to the larger work of the university and served tirelessly on dozens of committees. He was an effective chair of the English department from 1989 to 1993. In 1998, he was named the Faculty Research Lecturer, the highest scholarly honor that UCSB bestows on its faculty.

Richard was always proud of the two years he served in the Peace Corps in Togo, West Africa. On the way back from Togo, he spent some time in Florence, where he met his wife-to-be, Marie-Christine. The two of them helped in the rescue of books and manuscripts after the river Arno burst its banks in the fall of 1966 and sent floodwaters pouring through the city. Marie-Christine, now well-known in her native France as a writer of children’s books, and his daughter, Jessica, cared for him devotedly in the final six weeks of his life.