Stem Cells Take Center Stage

UCSB Hosts Forum on Promising Medical Field

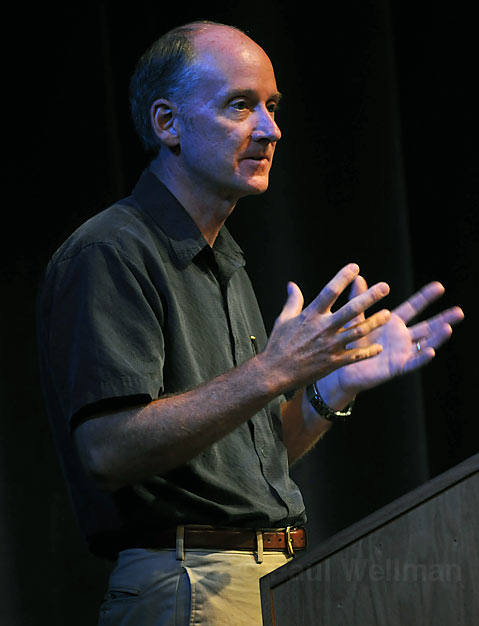

Jamie Thomson, the unassuming biologist who sparked a national tempest when he isolated human embryonic stem cells in his laboratory 10 years ago, told a theater full of UCSB students, faculty, and community members Friday that the real promise of this research lies in its ability to explain the human body’s most guarded secrets. Thomson, who became a UCSB adjunct professor last spring, was one of four researchers speaking at a town hall meeting sponsored by the university’s new Center for Stem Cell Biology and Engineering.

The father of stem cell research, chosen by Time magazine recently as one of the 100 most influential people in the world, was succinct and soft-spoken while laying out the range of research possibilities created by embryonic stem cells – including the nearly limitless potential for drug discoveries and toxicity testing. But he downplayed the more high-flying promises like transplantation. “It’s less about transplantation than about understanding the human body,” said Thomson. The other nationally prominent panel members included Alan Trounson, president of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM); Dennis Clegg, codirector of UCSB’s Stem Cell Biology and Engineering; and Lois Jovanovic, chief scientific officer and CEO of Sansum Diabetes Research Institute.

The meeting was a whirlwind of overhead charts and slides illuminating neuron cells, microscopic pieces of beating heart cells and other tissues and data. Almost all of the potential biomedical advances described Friday have the California Stem Cell Research and Cures Initiative (also known as Proposition 71) to thank. That initiative, approved by 59 percent of state voters in November 2004, provided $3 billion for stem cell research at California universities and institutions over the next 10 years. It is being credited with attracting world-class scientists to the state, including Wisconsin-based Thomson. Since 2005, three CIRM grants totaling $6.9 million have flowed into UCSB coffers for training and building research facilities that include a highly specialized lab for producing embryonic stem cells. The combination of that money and Thomson’s presence on campus has put UCSB on the stem cell map, though it’s also believed Thomson’s presence played a big role in the university’s winning its most recent CIRM grant.

One stem cell project at UCSB includes the studies of autism by Ken Kosik, MD, PhD. Kosik is codirector of UCSB’s Neuroscience Research Institute. He recently published a paper on certain microRNAs in the brain and the role they may play in causing autism. In UCSBs new stem cell lab, Clegg said, it will be possible to isolate stem cells from autistic patients for the purpose of studying their specific neurological processes, possibly leading to a cure.

During the question and answer session Friday, the mother of a child with Type 1 diabetes recalled being promised long ago that a cure was around the corner and she asked for a fresh assessment. “It’s the classic question; ‘When [will] we cure the disease?'” said Trounson. “It’s a hard one to answer. I don’t think it’s realistic to tell you it’s going to happen soon.”

Stem cells are special because they are pluripotent; they can grow into any kind of human tissue. They’re derived from five-day old embryos, which are essentially fluid-filled balls of cells that contain a clump of between 100 and 200 undifferentiated cells that are capable of reproducing themselves indefinitely. Recently, in separate efforts, Thomson and a Japanese researcher, Shinya Yamanaka (with whom he shared honors from Time magazine), used adult skin cells to create stem cells that look identical to embryonic stem cells, potentially bypassing the controversy. These are called Induced Pluripotent Cells, (iPC). All embryos used in stem cell research are donated by couples who underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures that resulted in more fertilized eggs than they needed. Jovanovic noted Friday that 400,000 frozen embryos are destroyed every year in California.