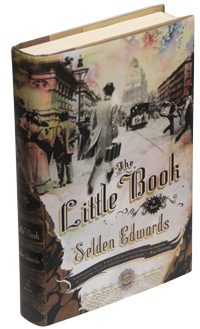

The Making of Selden Edwards’s Novel, The Little Book

Book of Ages

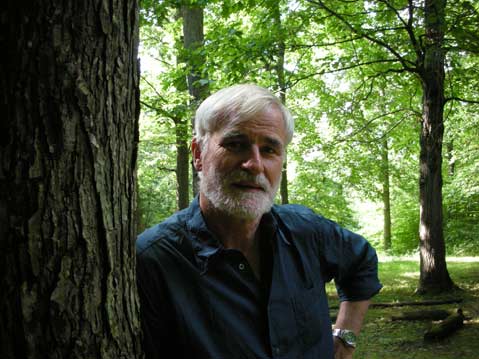

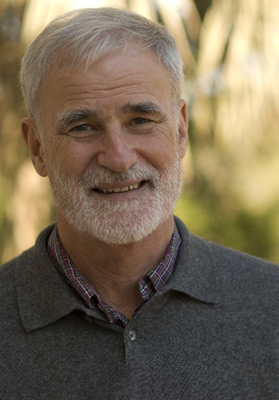

“Never give up” is an attitude that’s easier to espouse than to embrace, especially when the project in question has gone on for decades and the chances of success seem slim. Carpinteria resident Selden Edwards, former headmaster at both Sacramento and Crane Country Day schools, began working on a novel in 1974, and submitted the first of many final drafts as part of the requirements for a master’s degree at Stanford. During the next 33 years, the habit of working on what came to be known to his intimates as “Selden’s (unfinished) book” never left him. Winters and summers, when his colleagues were on vacation and his family was outside enjoying Santa Barbara, Lake Tahoe, or rural Michigan, Edwards would hole up in his study and write. More than six supposedly final drafts and dozens of rejection letters from agents later, upon his retirement in 2003, Edwards gave it one last try. The result of that final effort has now exceeded his wildest dreams.

The Little Book, Selden Edwards’s debut novel, will be published on August 14 by the Dutton imprint of Penguin Books, and the buzz in the publishing world is that this impeccably crafted and suspenseful tale of a world-famous American rock star who wakes up one day in Vienna, Austria, in 1897, will be the hottest fiction title of the fall. No less a luminary than Pat Conroy, author of The Prince of Tides, has said The Little Book is not only “a wonderful novel,” but that it “has a chance to become a famous one.”

So many first novels function as calling cards, devices intended primarily to introduce young writers to the market and begin the career-long process of building a reputation and a back catalogue. In a field typically dominated by bold-faced names and glamorous young writing school phenoms, how did Edwards, a teacher and school headmaster with a family and a constant stream of daily obligations, manage to slow-cook something so impressive that it sold to one of the world’s biggest publishing houses for very high six figures in just three days? And how will the buzz play out when the book hits the stores next week? Can Edwards’s novel, which combines time travel, prep school sports, rock and roll, modern philosophy, Sigmund Freud, and fin de sicle Vienna, become the next Da Vinci Code? Many publishing insiders think so, but as always in the popular arts, the story’s not over until the buying public has spoken. What follows is the tale of one man’s determination to keep going when most other people would have given up, and the unpredictable, last-minute collision of that individual’s personal idiosyncrasy, literary talent, and sheer endurance with a 21st-century zeitgeist that looks set to put a scholarly 68-year-old first-time novelist onto the best-seller lists and into the headlines of book review sections around the world.

A Slow Evolution

Literally for decades, part of the ambiance of Selden Edwards’s book project had been that no one could quite believe he was still working on it. Edwards’s friend and cousin, the painter Patty Look Lewis, remembers the years of toil with a mixture of amusement and awe. “I saw Selden on and off over the whole 30 years,” she said, “and you know, when someone tells you they are writing a book, well : a lot of people say they are writing a book, so you wait to see what will come of it. And with Selden, for a long time, that’s what it was, something that if you knew him well enough and felt comfortable with him, you might even tease him a bit and ask, ‘How’s that novel coming along?'” When I asked Edwards about the long march to completion, he was utterly candid, saying, “One interesting part of the story that maybe you haven’t gotten yet is that I really did try to get it published. I finished the book five or six times. It became almost a manic depressive practice, where I would change it quite a bit, and it got better each time. For instance, there was a five-year stretch where I worked on a version that eliminated the time travel. But it came back. I will tell you this, though: As hard as the rejection was, I am glad now that I did not publish the first draft.”

Lewis, like the rest of the author’s friends and family, only finally got to read what her cousin had been writing all these years after the deal was done. She reported an emotional experience. “When I did read it, I was on the verge of tears the whole time,” she said. “I just kept looking up at his name, which is at the top of every page, and thinking that this is incredible, he was always really working, and he was making something so complex and beautiful that it took that whole time.” For Lewis and others, The Little Book radiates a maturity that is exceedingly rare. She sees the book not only as a chronicle of several generations and places, but as the fulfillment of several lives. “There was this sense of familiarity, as though what he had written was a shared history,” she said. “I liked the erudition, and hearing about all the great artists and thinkers of Vienna, but then I began to see that the book also told the story of the Flower Children and the New Agers, and that it had reached a place where it wasn’t just about one life, but more about the evolution of the soul in history.”

Edwards’s editor at Dutton, Ben Sevier, agreed. He described his own first encounter with The Little Book, which he has now read many, many times, as magical. “I got up at 4:30 on the third day that I was reading it in order to be finished before I left for work, and when my wife woke up, I looked at her and said, ‘I think this is an important book.’ It really feels like it has been in the making for that whole time. Let me put it this way: I have yet to meet the person who could write this book in a year.”

We Can Be Heroes

Part of what has captivated those who have read The Little Book is its balanced, powerful style, which is reminiscent of the great masters of the literary tradition. But at the core of this extremely learned and knowledgeable book’s attraction stands a charismatic hero, Wheeler Burden, who in many ways resembles the author. A Northern Californian with an East Coast family, Burden leaves rural Sacramento County for a fictional Massachusetts prep school, St. Gregory’s, which sounds a lot like Nobles and Greenough in Dedham, the school Edwards attended. From there, Burden goes on to Harvard, then to fame as a rock star in the 1970s, and, eventually, to his final destiny in fin de sicle Vienna. Despite his many accomplishments and his general air of having led, as he puts it, “a blessed life,” the real-life Edwards can hardly be expected to compete with his outsized fictional creation. After all, Wheeler Burden led Shadow Self, a band that could (and, in the book, did) share the stage with the Rolling Stones at Altamont.

So there’s one partial explanation of how it was that Edwards persevered throughout the decades in bringing Burden’s saga to fruition: wish fulfillment. The Little Book has a positive hero-or three. It fits in the great tradition of the American novel as exemplified by Herman Melville and J.D. Salinger, but it aligns better with the novels of a figure who actually makes a historically accurate appearance in the book’s version of Vienna-Mark Twain. Like Twain, Edwards is something of a cockeyed optimist. Not without his misgivings about the direction of history or the state of the world, he nevertheless remains in possession of whatever mystical magic it takes to create, and believe in, an unqualified American hero.

“I’m not a cynical person,” contends Edwards, and his work bears out this self-description. While there are a multitude of ironies in The Little Book, the main characters mostly surprise the reader by rising to the occasion rather than sinking under the weight of the world. What’s more, their admirable behavior tends to take unexpected shapes, and to upend preciously guarded notions of rational order. This is not the macho heroism of yore. Without the slightest sentimentality, The Little Book builds inevitably toward an ethical climax devoid of censure or domination. The narrative, filled as it is with presentiments of great evil, nevertheless displays a guiding sensibility that revels in hard-won redemption and the practical magic of empathy and hope.

Locating the “moral” in a work of literary fiction is rarely worth the trouble. Even great books can be reduced by this to stereotypical lessons, like “be careful what you wish for,” or “don’t chase the whale that took your leg.” But what Edwards has built here is founded on years of study, a life devoted to teaching and schools, and an unshakeable faith in humanity’s ability to adapt and proceed, given the right kind of understanding and permission. As he said to me at one point, “The whole thing is about teaching.” Asked to explain his concept of heroism, Edwards offers an improbable literary antecedent-The Wizard of Oz-saying, “The biggest gift that my characters offer one another is what Dorothy gets at the end of her story, when she is given the belief that she is good enough, and that whatever else has happened in the past, she is now set free to be herself and to do her job.”

As his last name implies, the talented but undisciplined Wheeler Burden does not himself start out free to be himself or do his job, whatever that may be. The son of a famous World War II hero and the grandson of a proper Bostonian who participated in the first modern Olympic Games, Burden arrives at St. Gregory’s School with quite a lot of heavy, if elegant, baggage. One of the most intriguing ways that The Little Book works is as a kind of palimpsest, both of the capacious reading of its author in subjects as diverse as the history of psychoanalysis and the physics of the curve ball, and of the multigenerational experience that binds together the sons and daughters of the Ivy League establishment.

Best Boys

The so-called Establishment is a world Selden Edwards knows intimately, and his portrayal of it is as unsparing as it is affectionate. His father, Hal Edwards, was one of the founding farmers of the great 20th century California ranches. A namesake and relative, Harold Edwards, today is the chief executive of Limoneira Ranch, the holding company into which the family property near Santa Paula was folded. While his father developed the nascent California agriculture business, his uncle, C. William Edwards, acted as guardian of the gates to the eastern elite, serving as director of admissions at Princeton, Edwards’s alma mater, from 1950 to 1962. Further back, through a haze of orange-and-black-tinted football games, raccoon coats, and eating clubs, we can glimpse Edwards’s grandfather, Harold Edwards Sr., a successful Boston manufacturer of woolens, a staunch Republican, and an opponent of women’s suffrage. The time travel aspect of The Little Book is perhaps best understood in this light, as a lens through which to focus the contrasting characters and views of three generations of men who participated, albeit in remarkably different ways, in the same enduring institutions, and who even shared the experience of learning from the same cherished teachers.

For Selden Edwards, Princeton was something like what he has imagined fin de sicle Vienna to have been-a place of blissful refuge and impulsive creativity poised on the brink of a monumental historical transition into modernity. At Princeton in the early 1960s, future New York bankers and lawyers pulled pranks like sticking up the local commuter train on horseback and mock-kidnapping Smith College women before repairing to a clubhouse lawn for a private concert by Bo Diddley. This odd mixture of extreme privilege and carefree license crops up periodically in the novel, but it tends to be shadowed by something darker and more sinister, as befits a story the majority of which takes place in the tense years leading to the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In addition to an insider’s view of the eastern elite, Edwards brings to the book a lifetime educator’s sensitivity to the nuances of family relations and social institutions. Wheeler Burden performs a special kind of service to St. Greg’s, and then again to Harvard, when he fulfills the athletic expectations accorded to “Dilly Burden’s Kid,” as one of the book’s chapters is called. The sports scenes are among the best in the novel, as Edwards has an intuitive sense of where the big emotions that such contests generate reside. Wheeler Burden begins as a brilliant baseball pitcher, heroically striking out rivals from Dover School and then Yale, but ends his athletic career accomplishing equally amazing feats within the confines of entirely non-competitive games of Frisbee. All the while, the author conducts a thorough and playful examination of what sports legends do, not only on the field, but more importantly in the hearts and minds of the men and women who need and revere them. Part of Wheeler’s “burden”-a part that he often forfeits or rejects-is his role as exemplary boy, or man, and it is this strained sort of attention that sows the seed of his American downfall.

Persephone Rising

No account of The Little Book would be complete without mentioning the extraordinary success with which its female characters are depicted, and, more importantly, given their voices. It’s easy to forget that the book’s third-person narration, so lithe and effortlessly expressive, is presented as the work of Flora Zimmerman Burden, Wheeler Burden’s mother. In a typically subtle sleight of hand, Edwards appends an author’s note from Flora to the beginning of the book that disclaims the story’s “improbabilities” as the “parts that require more thought and explanation,” and something this 90-year-old woman is more than happy to leave to the reader to resolve. Indeed, the time travel aspect of the narrative is handled with remarkably little fuss or hesitation. The characters who wind up in Vienna are just suddenly there, the same way that Kafka’s Gregor Samsa simply woke up one day to find himself a bug.

In addition to being the putative author of The Little Book, Flora has also written one of the many delightful imaginary works of literature that the story introduces, a myth-based critique of Freudian psychoanalysis called Persephone Rising that is credited with jumpstarting contemporary American feminism. Without giving away too much, let it be said that Flora Zimmerman is not the only, nor the most central, fictional woman author represented in the novel. Another woman from another generation cuts an even more distinguished figure, at least in relation to her fellow characters. And this is because the most important thing that Wheeler Burden finds in fin de sicle Vienna is true love with a very brilliant younger-or is she older?-woman, Weezie Putnam.

In one of the book’s best scenes, Wheeler and his lover meet in an artists’ studio, a room full of pictures based on those of the real-life historical Vienna Secessionists: Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Koloman Moser, and Oscar Kokoschka. Listen to how Wheeler Burden, the 1970s American rock star, approaches the seduction of a proper late-19th-century Bostonian debutante.

“To everything there is a season,” he said.

“A time to embrace,” she followed, it coming as something of a relief.

“And a time to refrain from embracing.” She thought further on it. “So you are saying there is biblical permission for this sort of thing?”

“I am.”

“I think that is stretching things a bit.”

“Sounds like permission to me.”

“I don’t think that is what my aunt Prudence had in mind when she read Ecclesiastes.” With that, she rose and walked over to one of the large draped easels. “You know, there is something I have been very desirous of doing.” And she reached up and freed the sheet and pulled it from the first canvas. Both she and Wheeler gasped and stared in amazement. There before them was a large, brightly colored painting of a totally naked woman, surrounded by color and gold, with a look on her face that Wheeler would later describe as “dreamy ecstasy.” Weezie walked over to the first stack of paintings and again pulled off the sheet. This time a man and a woman, both clothed but with the most sumptuous expression toward each other. She moved the painting and found beneath it yet another riot of color. Then another. Then another. Before 10 minutes had passed, the two lovers found themselves surrounded by brightly colored paintings, all of them, to one degree or another, radiating an irresistible sensuality.

The spell cast by the great artists and thinkers of Vienna-the painters, as above, but also the musicians such as Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss, the philosopher Wittgenstein, and most of all the ur-therapist and intellectual revolutionary Sigmund Freud-winds through The Little Book like a musical motif that becomes a flowing current of passion. “Ardor” is one of The Little Book‘s key terms, indeed the kind of word that can get one into trouble in the 1890s, and one hears ardor in Edwards’s voice as he describes his admiration for the book’s principal historical character. “I revere Freud,” he said, “because the contribution he made was to demonstrate the value of truly fearless introspection. Freud had a kind of doggedness, an insistence that introspection not stop, that it should keep going until the patient was free to devote his or her life to the core human activities, love and work. And that’s what Wheeler Burden is able to do for his beloved. He sets her free from her past to do what she was meant to do.”

The Little Book is unlike any novel I have read. In its historical scope it resembles Anthony Powell’s wonderful series A Dance to the Music of Time, but with the introduction of the fantastic, through the device of time travel, and myth, through the arts and psychology, it delivers a very different and rather more modern experience. With so many volumes published in such a wide variety of styles today, it’s hard to tell if any new book will survive for even a year, never mind gain literary immortality. But this novel, rooted in the work of more than 30 years, has as good a chance as any in recent memory of withstanding the test of time and becoming a classic.

4•1•1

Selden Edwards’s The Little Book will be released on Thursday, August 14. That evening at 7 p.m., Edwards will appear at Borders in downtown Santa Barbara (900 State St.) to read from the book and sign copies. For more information, call 899-3668.