Voices Rarely Heard

In the Shadows of Paradise Illuminates Santa Barbara's Undocumented Economy

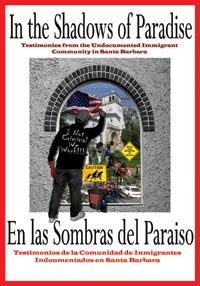

One year ago, a group of professors, students, and other activists within the social justice group PUEBLO (People United for Economic Justice Building Leadership Through Organizing) began interviewing undocumented immigrants about their lives here. The resulting book, titled In the Shadows of Paradise, or En las Sombres del Para-so, is scheduled for release November 18. No matter where you stand on the subject of illegal immigration, this small collection, just 64 pages long, shines light on the unique struggles of a population that-despite its central role in the region’s history and current life-remains obscure to most other Santa Barbarans.

Recorded and collected under the guidance of Mary Watkins, a professor in Pacifica Graduate Institute’s depth psychology program, these stories focus on the speakers’ countries of origin, border crossing, first impressions of the U.S., senses of identity, reasons for staying, and their experiences of working without proper documents, driving without a license, and deportation. The book also includes smart, concise histories of the pertinent Latin American countries.

All of the profits from In the Shadows of Paradise, self-published with a grant from the Karuna Foundation, are being donated to PUEBLO’s Education Scholarship Fund to help students who are ineligible for financial aid because they are not citizens.

The following excerpts use the same pseudonyms as In the Shadows of Paradise. – Martha Sadler

Denise, 19, Mexico

I was born in Mexico 19 years ago. As a young child, my natural surroundings made up most of my toys-from mud I made sun-dried pots, from plants and berries I made play food. Although I remember myself as happy, my siblings, mother, and I all slept on one bed in a small, dilapidated room with no flooring but the bare dirt. We used an outhouse and had no real shower. At the age of four, I would ask neighbors for loans of milk and food. I felt that my life there was great, but as a child I was naive and ignorant of my harsh reality.

I remember the day I lost my father [when he left for the U.S.]; I recall running in and out of the house looking for him, crying desperately. I had been his only little girl and he my only papi [daddy]. He remembers that day, too, and has told me that he saw me crying from the corner of the street. He could not hold back from crying himself and almost went back home to be with us, but the necessity to earn money and provide a better life for his family was stronger than his love for me.

My mother did not have a job and had to care for four children. The economic forces that continually depreciated the standard of living in Mexico pushed my family to emigrate. My mom immigrated to the United States in 1993 along with my siblings and me.

: Once I started school, studying became an escape from my family problems. Soon education became an important part of me. American society instilled in me that working hard and being educated would take me far in life, and of this I am very proud. Working hard is all I have done my whole life. I have been dedicated to education, receiving numerous awards for academic achievement, good citizenship, and extracurricular activities, and always envisioning that one day I would attend college.

During my high school years, my identity as an undocumented immigrant was brought out of the shadows, not to others, but to myself. Talking about one’s status for an undocumented immigrant is taboo. When most of my friends were applying for financial aid, I could not.

I constantly wished I was not in this situation, to the point of self-hate. I did not want to be seen as a criminal, an alien, or an illegal.

: In spite of my struggles with identity, I graduated from high school at the top of my class, receiving various honors and awards. In fall 2006, I entered UCSB as a sophomore, having passed many advanced placement tests in high school. I am now a second-year student at UCSB and have been doing really well, even receiving Dean’s Honors. : I am co-chair of a campus group that focuses on advocating for a more equal education for undocumented students. I am also part of the California DREAM network, which has led a campaign to pass the Federal DREAM [Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors] Act, a piece of legislation that would provide a path to citizenship for undocumented students.

Fortunately, with help of loved ones and loans, I have been able to pay for tuition, since I do not qualify for financial aid because of my [non-legal resident] status. However, times are very difficult. : That has led to my temporarily withdrawing from school.

Many would say that I have come a long way for an undocumented student, but there is so much more that I still want to accomplish. : Although I have a very positive mindset, I face uncertainty after I graduate. Will I be able to exercise my degree? Will I be able to afford graduate school?

Ramiro, 29, Mexico

I have cousins who have been coming to the country for years. I saw that they always came back home from the U.S. with their pockets full of money. They were able to build a nice house and buy a good truck after working for a while in this country. They told me to find my way toward “El Norte.” Each time my cousins returned from the U.S., their faces were happy. When their money was running out, they became worried and talked about going back one more time.

: When I was 21 years old, my brother paid around $3,000 so I would be the next to cross the American border. I crossed the border with 14 other Mexicans who lived in my town. The first time we tried to cross, I almost left my intestines on the desert. It was a dark night when the U.S. Border Patrol ambushed us. I just remember that I ran as fast as a rabbit and did not see the fence that was made of iron and was as thorny as a rose. I could not get through, and it threw me back on the rocky, cold soil. : The Border Patrol took some of our companions who were captured. I thought I was left all alone in the desert and that I would never see my mother again. I was in such despair that I cannot explain it in words, but thanks to the Almighty, the coyote [taking us across the border] came to get me and the other Mexicans who were also hiding. They were as quiet as scared mice. It hurts me each time I think about it because I could have died there in the enormous Arizona desert all alone. My poor mother would have died of sadness after learning about my terrible fate, or maybe she would never have known about my fate, just like so many other mothers.

Omar, 20, El Salvador

I was a young boy during the civil war in El Salvador in the 1980s. A curfew robbed people of the liberty of enjoying the night. In the mornings, when we left our homes, we saw bloody dead bodies on the walking paths as if they were road kill. The civil war created more than just fear among Salvadoran people; its ramifications were immense. Dreadfully deteriorated economic conditions resulted, and my mother decided to immigrate to the U.S. in 1991, right before the signing of the Peace Accords of 1992, which ended the war. I was four.

: After an exhausting seven days, I finally arrived in San Diego where a short, fat lady accompanied by a man was waiting for me. At first, I did not recognize this couple; they were strangers to me. However, the lady gave me an almost endless hug as if I was her son. I did not recognize that this lady was my own mother, pregnant with my sister and accompanied by her new partner.

The eight-year separation from my mother had left me with very few memories of her and created a great wall between us, which continues to affect our relationship today.

In those early days, I continued to be separated from my mother because she had to work. While my mother was at work, I would stay alone with a TV in a very small apartment in Pico Union near MacArthur Park, one of the poorest areas in Los Angeles. I felt like a caged bird, a strange feeling that was so different from the immense freedom I felt in El Salvador.

Daniel, 32, Mexico

I am 32 years old and from Zacatecas, Mexico. I arrived 15 years ago to the City of Los Angeles and then decided to move to Santa Barbara. I have always worked as a day laborer, but the last few years have been very difficult for me since I was deceived by someone who hired me along with other day laborers.

They hired 20 of us in total. They took us to a ranch [between Carpinteria and Montecito]. : The person who hired us offered us tents so we could live on the ranch and save money. We worked 10-12 hours a day from Monday through Sunday. The first two weeks we only worked from Monday through Saturday with an initial cash salary of $12 an hour. During those two weeks, they also took us grocery shopping. On the third week, we started having problems when they decreased our salary down to $8 an hour because they took that money to pay taxes. They also took away the portable toilet because the owner did not want to continue to pay for its maintenance. : Even worse, they locked us up in the ranch without allowing us to leave; we were guarded the entire time by men with weapons and by guard dogs.

: One day, one of the workers rebelled by trying to escape, but failed and was caught. We didn’t see him the next day; he most likely was killed because they would always threaten to kill us or call immigration if we didn’t obey them. : One of the things that made this so sad was that the ones who did this to us were our own people who were ordered to do so by their boss who is American.

I thank God that one of the other workers finally was able to escape and notify a radio station of what was going on. They sent help, but it was only because of that that we were able to recover our freedom. We were never given any of our salary. I was very hurt because for more than five months we worked so hard and received nothing.

We continue to work as day laborers, but where we presently are located there is someone who organizes us using a list and number system, and those who come to solicit our labor are asked for a license and address of where the work will be. The minimum salary is $10 an hour for a minimum of four hours.

Each Sunday, I spend $5 to call my family and hear my wife and children’s voices. They tell me that they are finishing building our home with cement floors. I am full of joy because my children can wear shoes to go to school and can also wear better clothes. I try to send all the money I earn to Mexico so that my family will not be in need.

Luz, 22, Mexico

My family and I emigrated from Mexico to the United Stated 21 years ago, in 1985. Shortly after my 12th birthday, our visas expired, at which point my parents petitioned to adjust our immigration status.

: October 1997, 11:37 a.m. Wearing a neatly pressed dress, I stood in the middle of an oddly shaped courtroom lined with wooden seats. My brother, sister, mother, and father stood to my right. I tugged at my dress hoping to distract my mind from an overwhelming sense of something I had not quite identified, but I could not. In broken English, my mother and father desperately attempted to plead our case before the judge, still wondering why our notary had failed to show. My mind hit a roadblock as the immigration judge explained that there was nothing more he could do for us. We were the victims of fraud, he said, an unfortunate but commonly seen scenario in immigration proceedings.

We later found out that our attorney had falsely filed for us under political asylum, knowing full well that Mexican citizens are denied such claims nearly 90 percent of the time and immediately are put into deportation proceedings. My parents had worked for months, pooling our resources to pay for our application. We had rested our hopes and our future on our notary and his associate attorneys.

I refused to let my mother see me cry. My mother struggled to do the same. I had to be strong; we all did. It was then that I looked across the room and my eyes met a set of slim, black-framed numbers: 11:37 a.m. That was the time. That day, my definition of home unexpectedly was pulled out from beneath my feet. The shame of being different, something foreign, an “illegal alien”-as the law chooses to call us-became so overwhelming that growing up I lied so that I could blend in.

: It was clear my status would keep me from access to financial aid for college, so, at the age of 15, I entered the large economy of the invisible: the undocumented. I worked alongside my mother as a housekeeper. For four years, my family and I worked to save money for my sister’s college education and mine.

: The barriers I have been able to overcome and my academic achievements have been possible because of my family’s work and support, and our faith in God. Like all children, my parents are my heroes, my role models. It is heart-wrenching to see them humiliated and taken advantage of by their employers, knowing that they do not have the luxury of quitting because finding other employment is difficult due to our immigration status.

Emanuel, 26, Mexico

At work, I am always scared and thinking, “What if something happens and they find out about my situation?” It is hard. I wish I could get a better job. I guess that is my goal-to have a job where I am happy to go to work because I like what I am doing and where I am being treated fairly and am not afraid to stand up for my rights. At my old job with the moving company, the employees were abused. The pay was okay, but they overworked us. The pushed us to our limits and never appreciated all the stuff we did for them. We always feared that if we spoke up, they would fire us.

Ideally, I would like to work in the multimedia industry; I really like to do creative artwork, but realistically, all I want is a job where I know that years from now, after working hard, I will be able to retire and get a pension and benefits, even if they are little. : If you get injured at work, you won’t speak up because you know that because of your situation, you are replaced easily. : Having security in a job is what I want. I want security. I don’t want to be afraid that I am going to lose my job any day. I want to be appreciated, or a least acknowledged for the work I do.

Ronaldihno, 19, Mexico

The first time my mom left Mexico, she only brought my brother with her. My brother was a baby. By the time I arrived over here, he already was walking. I was probably like three or four. We stayed here for two years and then we went back.

I immigrated to this country again when I was 10. I [had been] living with my grandma because my mom abandoned me-not abandoned me, but she just couldn’t take me with her because it was too much for her. I told my mom I wanted to be with her and she was like, “Just wait for a year so I can get myself established here and get things working.”

I started liking it because I had a cousin who was here. He would take me to the arcade to play video games. It was pretty fun at that moment. I was happy. I don’t know if my parents were happy. I think they were happy that we were all together, but my dad : he always gets mad at everything.

When my cousin moved, a lot of things changed. He was older. He kind of looked after me because he had a brother who went through gangs and he didn’t want none of us to be in gangs. He left. I didn’t have nobody. Well, I started hanging out with a friend who lived on the corner, but then we started hanging out with older guys, gangster guys. I was 13, probably they were like 17, 16. And that’s when everything changed. My life changed.

Well, my parents were there, but not when I needed them. They weren’t there for me. When I would tell them that I wanted to join soccer at the afterschool program at La Cumbre, because I love soccer, they would say, “Yeah, do it. Whatever you want, do it.” I didn’t have the push, you know, to push me up. They weren’t paying attention. My mom-working. My dad-working.

I started hanging out with gang-related people. I didn’t see them as gangsters; they would play football with me. They were cool guys.

I was in Youth CineMedia, which helped me. It gave me the push I needed to get up and do something with my life. I changed my evil ways for the good ways. Now I’m more like an activist fighting for my rights and other people’s rights. Even though I’m still invisible. I’m still an alien, whatever they want to call it. I mean, if they ever want to reform immigration, I’ll be glad. Even if I don’t get citizenship because of my past, I wouldn’t mind for other people to get it, so that way I would leave this country knowing that I did something for this country, for my people.

Alma, 42, Mexico

[My husband] is from the state of Michoacan, Mexico. There, he and his family cultivated their land. If it rained, they would work, but if it didn’t, they would lose their crops.

: Some of my children were born in the U.S.A., and as a result are U.S. citizens; the rest are not residents, so this issue creates alienation within the family. Those born in Mexico graduated from high school and now are attending City College to get a general education. They struggle with looking for good jobs and [not being able to get] a driver’s license, which is very necessary for them to move from home to school and back. I’ve noticed that they feel desperate when they have to wait so long for the bus to get to work. They say that they spend their whole day on the bus to get from one place to another.

Mateo, 39, Mexico

My license was not renewed because I didn’t have a Social Security number.

: I kept on driving without telling my boss. One day, the police stopped me because one of my lights didn’t work. They confiscated my truck with all of my tools. I waited a month to get back my truck, but I wasn’t able to because I only had an expired driver’s license. The truck cost me $5,000 in addition to what I paid for my work tools. I had to pay a $260 fine for having an expired driver’s license, and $70 for each day my truck was impounded. It all summed up to $2,300 to be able to get back my truck, but I needed a driver’s license that wasn’t expired. It has been very difficult for me not having a Social Security number; consequently, I have not been able to renew my driver’s license.

Now I drive a $500 car because I know the police are going to stop me one day and confiscate my car because I don’t have a license. But I would rather take a risk driving than ride the bus, because one can spend hours on the bus trying to reach a destination. If I used my bicycle, I would need to wake up at 4 in the morning to get to my job at 7. I hope that one day people realize how important we are to this country.

Abril, 21, Mexico

The Inevitable: It was Thursday, December 20, 2007, the fifth day after my finals, and I woke up with an incredible sense of fear in my heart. Somebody was knocking so hard on the door that it seemed at any moment, they were going to break down the door. I noticed that it was only 7 a.m. and nobody wanted to get up to open the door. They yelled, “Open the door!” I remained awake, but in bed. Finally, somebody opened the door and what I heard next broke my heart and left me paralyzed with fear. At first I thought it was the police, but later I heard that there were many of them and each of them had a flashlight and started counting us. They came to my room with a flashlight and yelled, “There are two more in here.” : The last thing they said was, “Contact your attorney, because we will be back.”

: I found my mother crying in the living room and my eyes exploded with tears. They had taken my father.

: The attorney told my parents that the only way to defend us would be to lie about our arrival date to the U.S. They gave my mother information to memorize just before we went to court. My father did not know how to lie well and my mother attempted to help him respond. Finally the judge yelled, “Lady! I am asking your husband the question!”

My mother refused to be quiet, and the judge ordered her to be taken out of the courtroom. My siblings and I also left the room. My mother was sitting at my side when the attorney came out and told us that we were ordered to be deported. [We had paid $8,000, but there] wasn’t anything more he could do for us, so he would no longer be handling our case. I heard my mother yell, “No! My God, that can’t be possible!” After, I saw her cry uncontrollably.

: My father returned to the U.S. (it cost us $2,000) to help my mother save a little bit of money for our return to Mexico, where we will return to poverty, because we have no home, job, or relatives.

: I can’t help but feel that in some way my life and that of my family has completely changed. We are again hiding from immigration so that we can survive in the country we have lived in for 16 years. The difference now, for which I am very proud, is that I will be graduating with my degree in chemical engineering.

Sometimes the pain keeps me from making sense of what I really feel about the immigration agency, judges, attorneys, or agents who barge into people’s homes and take from them all they have. But I always know what to think about those who have helped me fight so that I could attend college, those who helped pass AB540, and those who continue fighting for the educational rights of immigrants. They are the hope that I have asked God for every year.

4•1•1

UCSB’s MultiCultural Center will host a discussion and reading from In the Shadows of Paradise on Tuesday, November 18, at 6:30 p.m. There will be a book-release party on Wednesday, November 19, at 6 p.m., at La Casa de la Raza. In the Shadows of Paradise will be available at Chaucer’s Books.