The Uncertain Fate of Independent Bookstores

What Does the Future Hold for Santa Barbara's Booksellers?

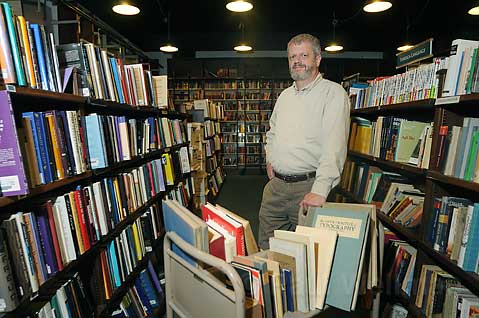

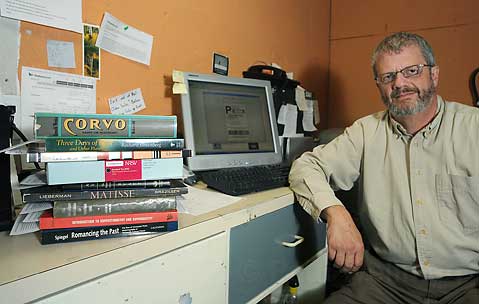

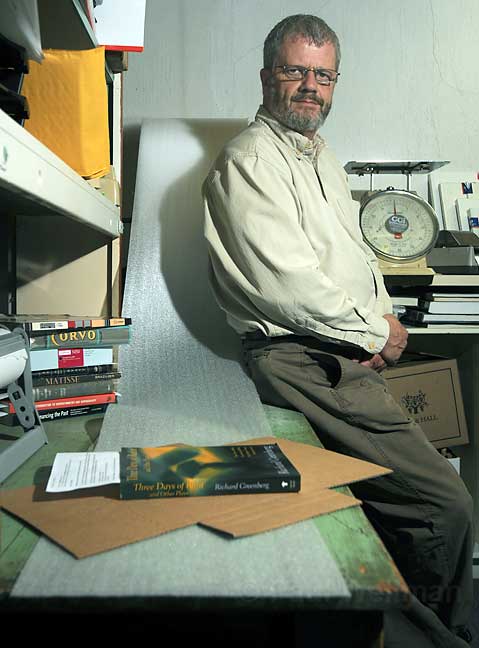

It was 10 years ago when Eric Kelley first realized how thoroughly the Internet was going to transform his business. The proprietor of the Book Den, California’s oldest used and antiquarian bookstore, Kelley had come into possession of a first edition, two-volume set of Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair by William Morris, the 19th-century English architect, designer, and writer. Kelley, who has owned the Book Den since 1979, has a knack for sniffing out precious old books, and these volumes, although in imperfect condition, were particularly valuable.

“On a Monday, I got an email from a man living in Kyoto, Japan, who was interested in the books, but was worried about their condition,” Kelley explained over coffee at the Coffee Cat recently. “I immediately emailed back some photographs. On Tuesday, the guy wrote back and said he’d take them. I took his credit card, and I sent the books off to him that afternoon.” Kelley paused. “On Friday, I got an email saying that the books had arrived in Kyoto, he was very happy with them, and they were now part of his small but treasured William Morris collection.”

An affable former hippie with a straggly goatee and a scar over his left eye, Kelley is a natural entrepreneur. As a child he was constantly devising new schemes to make pocket money, and his purchase of the Book Den was motivated partly by his knowledge that the profit margin for used books is substantially higher than for new books. In the Internet, Kelley recognized an opportunity not only to expand his customer base, but also to rectify the chief drawback to used bookselling, which is slow inventory turnover. Still, until the Morris sale, he hadn’t fully realized how profoundly the Internet was going to change the bookselling business.

Tough Times in the Book Business

Today, online sales account for 40 percent of the Book Den’s business. This may be startling, but in fact it has become commonplace among used and antiquarian bookstores, which often carry obscure titles of interest only to select customers, the base of which expands enormously online. However, what the Web has done to enlarge and internationalize bookselling for Kelley and other independent bookstore owners, it has also done for Amazon, and for millions of people with too many books in their garage. The prices these online sellers get can be astonishingly cheap: I just typed “Hamlet” into Amazon’s book search and came back with a low price of $1.20, plus shipping. How can bookstores compete with $1.20?

The answer appears to be that they can’t. For months, iconic bookstores across the country have been shutting down-Dalton’s in L.A., Robin’s in Philadelphia, Olsson’s in Washington, D.C. Even the mighty Powell’s, of Portland, Oregon, is in financial trouble. And the chains are faltering as well. Borders may be near bankruptcy, and Barnes & Noble’s shares have been plummeting, even as it has lain off hundreds of corporate employees. Among publishing houses, the crisis is even more pronounced. And although some of the bloodletting is ascribable to the recession, the problems in the book business long predate 2008.

Is there any hope for smaller independent bookstores, which occupy, after all, an important place in the identity of any town or city? I put this question to Roy Blount Jr., the writer and humorist who currently heads the Authors Guild, and who, just before Christmas, wrote a witty, open plea to Americans to patronize their local bookstores, and buy lots of books. “Everybody who cares about books is worried about what will become of bookstores,” he replied. “I’d say the more local and personal and informed a store is, the more it will provide what the Internet can’t.”

Like many independent bookstore owners across the nation, Kelley is in the process of testing Blount’s assertion. He currently is working to renew his rental agreement, but says he doesn’t know how long the Book Den is going to be around. “My landlords have always been very nice to me,” he said, “but considering the current economic situation, are they willing to be as generous as I need?”

Santa Barbara’s Shifting Literary Landscape

On a bright weekday morning last month, I visited the Book Den, which occupies a stately building on East Anapamu Street, just across from the public library. It has a cultivated air: The lighting is mellow, classical music plays softly over the sound system, and the books-there are, at any given time, between 20 and 30 thousand of them-are diverse: hardcovers about architecture, photography, and art in the front of the store; religion, spirituality, and self-help in the middle; mystery and sci-fi in the back. Lining the walls are fiction and non-fiction.

The store’s tenure in Santa Barbara dates back to 1933, and when Kelley bought it in ’79, he was in the enviable position of inheriting a profitable, well-liked bookstore located in the heart of downtown. At the time, Santa Barbara was home to a vibrant literary scene. There were a number of small but important publishing houses-most notably Black Sparrow Press, which published Charles Bukowski and Joyce Carol Oates-and an amazing quantity of bookstores. In 1985, there were 21 used bookstores in Santa Barbara alone.

Today, Santa Barbara and Goleta together have six used bookstores, and 20 bookstores total, including Borders and Barnes & Noble. What accounts for the downturn? One factor is rising rents. In 1980, the rent for the whole ground floor of the Odd Fellows Building-which houses the Book Den and Paradise Found-was $750. Kelley declined to divulge his current rent, but suffice it to say, it’s not $750. The rent issue was made worse in 1990, with the construction of the Paseo Nuevo shopping mall. Paseo Nuevo put into motion the commercialization of downtown that made storefront real estate stratospherically valuable, and attracted the attention of a number of chains, including Barnes & Noble and Borders.

With the possible exception of Chaucer’s Books, whose owner declined an interview, Borders and Barnes & Noble no longer have any direct competition from local, independent bookstores. This probably accounts for the longevity of those stores that remain. Unlike the Earthling, or the Kisch bookshop, both downtown bookstores that went out of business after the arrival of Borders and Barnes & Noble, many of the survivors have a niche to fill: used books, antiquarian books, paperbacks only, and so on. The question now, though, is whether Santa Barbara bookstores can endure a sea change in the way books are bought and sold. More than big chains or high rents, the most serious challenge to bookstores today is the Internet.

The Changing Face of Book Retail

Tori Detrick is a 27-year-old Web advertiser. She lives on the lower Westside, and belongs to a large book club. An avid reader, she buys the vast majority of her books online; she rarely visits bookstores or the library. “Buying online is so much cheaper,” she said, “and, it’s more efficient. It’s hard to find the time to go to the library or the local bookshop when I could just order it quickly online and get it the next week.”

Every year, more and more of us migrate online to make our purchases. This is particularly true with books. In 2007, online book sales were only narrowly beaten out by sales at chain bookstores. This year, for the first time, more books are expected to be sold online than in stores. Although Borders and Barnes & Noble sell online, both have been hit hard by the rise of Amazon, eBay, and other online retailers. Independent bookstores have fared no better.

“Online retail has been horrible for independents,” said Jim Milliot, the business and news director of Publishers Weekly. “As much as the expansion of the chains 15 years ago hurt independents, the growth of Amazon in particular has been really tough to compete with. The prices they offer, the selection they offer, the convenience-there’s just no way the independents can fight back.”

Among local booksellers I spoke with, there was a near universal consensus that the Web is threatening their ability to remain profitable. Jerry Jacob, who owns the small used and antiquarian bookstore Lost Horizons on Anacapa Street, admitted to a dark view of the future of bookstores: “I sometimes wonder if we’re in a dying business.” I heard a similar sentiment from Ruta Safranavicius, owner of Paperback Alley on Hollister Avenue in Goleta. Safranavicius pointed out that while most retailers are hurting right now, the threat to bookstores predated the recession. Moreover, she said, the threat isn’t just people buying books online-it’s people reading books online.

In 2004, Google began scanning books from libraries all around the world, and making the texts available, for free, on the Internet. It has now scanned more than seven million books. At some point in the relatively near future, Googlebooks.com could become the largest library-and the largest bookstore-in the world.

Of equal concern to bookstore owners are “e-books”-digital books that Amazon will send to your computer or your Kindle, a small, electronic reading device that is meant to replicate the readability of paper and minimize eyestrain. The market for e-books, although growing rapidly, is still less than one percent of the total publishing business: About 400 million paper books were sold in the United States in 2008, and Amazon sold 380,000 Kindles in 2008. Nevertheless, the specter of the Kindle has raised fears among many booksellers that in the future, far fewer physical books are going to be printed.

Kelley said he believes that digital books will never eclipse their physical counterparts-he pointed out that movies didn’t put radio out of business, and television didn’t put movies out of business. Still, he worries that the book business is being atomized to such an extent that it will soon be difficult for large, independent, general interest bookstores to stay in business. “Everybody says, ‘Well, you can specialize in this or that niche,'” he said. “But the niches keep getting smaller, and at some point the niche isn’t large enough to warrant having a shop.”

Change at What Cost?

Before the advent of Paseo Nuevo, the locus of downtown Santa Barbara was the corner of Anapamu and State streets. Within a block radius were the Book Den, the Museum of Art, the Granada, and, in its later incarnation, the Earthling bookstore and cafe. For a literate community still faintly suffused with a bohemian feel, this local, cosmopolitan concentration seemed appropriate. But things change. When the Earthling eventually was driven out of business by its corporate nemeses-to much hue and cry in the community-I remember wondering how bad Borders really was. Here was a bookstore that stocked tens of thousands of titles in a well-lit building equipped with a coffee bar and comfortable seats. How evil could it be?

A similar question might be asked of Amazon and other online booksellers. Almost any book one could conceivably want can now be found online, including books long out of print. The efficiency of online booksellers, and the savings they afford, are unrivaled, and it’s no surprise that most of us who buy books use them.

However, it is an incontrovertible fact that by migrating online for our purchases, we’re endangering our local stores. In 2007, Ted’s Books on De la Vina Street closed its doors, and this past year, Internet commerce was directly responsible for the shuttering of Morninglory Music and Video Schmideo. Before we let any more of Santa Barbara’s independent bookstores disappear, we might take stock of what they mean to us, and what character and texture they give to our community. What value do they hold for us, and can we imagine a future without them?

Toward the end of our interview, I asked Kelley why independent bookstores are worth saving. “A bookstore is a place you can go that’s not your home and not your work, where you can be surrounded by things and people you’re interested in,” he said. “You can browse: The serendipity of the book on the shelf next to the one you were looking for, that you’ve never heard of but is really cool-that can’t be replicated on the Internet. Being seduced by all of the aspects of physical books that are designed to seduce you-the covers, the type, the quality of the paper :” Kelley paused, and leaned back. “And let’s give my staff, and the staff of all bookstores, credit. They’re interesting people. They know stuff about books. They may know something that you don’t about your subject, or they may be in a position to help you find out.” He smiled. “And they can recommend the good, cheap restaurants.”

Santa Barbara’s Independent Bookstores

Bennett’s Educational Materials

5130 Hollister Avenue

Santa Barbara, CA 93111

964-8998

Book Den

15 East Anapamu Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

962-3321

Chaucer’s Books

3321 State Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93105

682-6787

Front Page

5737 Calle Real

Goleta, CA 93117

967-0733

Isla Vista Bookstore

6553 Pardall Road

Isla Vista, CA 93117

968-3600

Lost Horizon Bookstore

703 Anacapa Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

962-4606

Metro Entertainment

6 West Anapamu Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

963-2168

Pacific Travelers Supply

12 West Anapamu Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

963-4438

Paperback Alley Used Books

5840 Hollister Avenue

Goleta, CA 93117

967-1051

Paperback Exchange

1838 Cliff Drive, Ste. A

Santa Barbara, CA 93109

966-3725

Paradise Found

17 East Anapamu Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

564-3573

Ralph Sipper Books

10 West Michelorena Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

962-2141

Randall House

835 Laguna Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

963-1909

Read N’ Post

1046 Coast Village Road, Ste. B

Santa Barbara, CA 93108

969-1148

Tecolote Book Shop

1470 East Valley Road

Santa Barbara, CA 93108

969-4977

Thrasher Books

827 Santa Barbara Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

568-1936

Unity Church Metaphysical Bookstore

227 East Arrellaga Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

966-2239

Vedanta Temple Bookstore

925 Ladera Lane

Santa Barbara, CA 93108

969-5697