Carpinteria School Board to Decide Mascot Issue

The War Over the Warrior

It seemed clear enough to Eli Cordero-the Warrior mascot images displayed all over his high school campus were offensive and should be removed. They are caricatures of Native American people, he thought. Many incorporate feathers, which are considered sacred to his Chumash spiritual tradition. And overall, how could a race of people serve as a plaything for a publicly funded school?

But the issue of removing the Carpinteria High School images-murals, sculptures, tile art, letterhead logo-turned out to be anything but clear and simple. After Cordero proposed the change last spring, a “save the mascot” movement was launched to preserve what some people see as years of sports history and tradition. A faction of the community refused to accept the board’s 3-2 vote to keep the Warrior name but get rid of the Indian-themed icons.

After a year of community tension, the Carpinteria mascot controversy may be settled on Tuesday, March 17, when school board trustees are scheduled to review recommendations of the Native American Imagery Committee, a group of people appointed by the board to evaluate each individual mural, artifact, and emblem. Based on the committee’s findings, the images may be retained, removed, or altered.

Certain factors work against Cordero’s proposal. For example, last November’s election changed the makeup of the school board and Cordero’s supporters believe the votes are there to rescind the prior decision. Also, the school district secured a legal opinion that states “continuing use of Native American imagery and the Warrior nickname does not violate any federal, state, or local law on its face.”

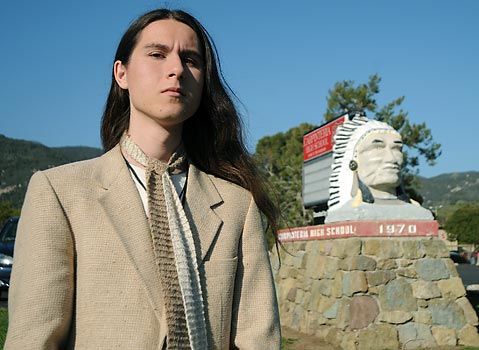

Eli Cordero, now 16, understands better than anyone that his battle is all uphill. After months of delay and acrimony-he’s received two death threats-Cordero is just as passionate as the day he presented his petition signed by 50 fellow students, as well as a stack of documents related to Indian mascot challenges nationwide.

“Coming from a native perspective, it’s hard to explain to other people. They don’t understand why I have long hair, that I’ve been raised in the culture, having danced my dances and sung my songs,” Cordero said. “The images are run-of-the-mill stereotypes of Native Americans. They are on floor mats and tables, they get walked on and eaten on. It’s very disgraceful and demeaning.”

Cordero is not alone in his fight against the Warrior mascot. Individuals and organizations have formed CARE (Coalition Against Racism in Education) to support his cause. A sampling of its 27 members includes the American Civil Liberties Union of Santa Barbara, American Indian Movement West, Black Student Union of Santa Barbara City College, El Congreso Students Association of UCSB, and the Fund for Santa Barbara.

On the other side, a strong showing is expected from people supporting the Warrior Spirit Never Dies campaign. Businessman Don Risdon is a lifelong Carpinteria resident who graduated from Carpinteria High in 1975. He especially defends the logo used by the school and its athletics department-a design of the letter “C” with an arrow and two feathers. The student who designed it came to one of the heated board hearings and explained the elements, he said.

“The ‘C’ is for Carpinteria, and the arrow is for moving forward, and the feathers are a symbol of peace,” said Risdon, who played on the school’s tennis team. “So I don’t think that is offensive.” Risdon also believes the imagery committee wrongly included “outsiders”-people from Goleta, for instance. And he points to the school board election as proof that Carpinterians want to retain the mascot images.

Recently seated boardmember Lou Panizzon ran and won on a platform strong on keeping the mascot images. Panizzon, formerly a coach and principal at the high school, acknowledges that Cordero finds the Indian images offensive, but “lots of things offend people. Like smoking. So we’ve made rules dealing with smokers, but we haven’t banned smoking,” he said.

Providing a contrast to Panizzon is his fellow trustee Leslie Deardorff. She hopes the current board respects last year’s vote and urges her colleagues to honor the recommendations of the committee, whatever those may be. Deardorff refers to a statement by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights condemning the use of Native American images and nicknames as sports symbols. Published in 2001, the statement claimed the images are “particularly inappropriate and insensitive in light of the long history of forced assimilation that American Indian people have endured in this country.”

“Most people in this community just want the school to drag itself out of the 19th century and into the 21st century,” she said.

The legal opinion from the school district’s attorneys, which can be found on the Carpinteria Unified School District’s Web site (cusd.net), is a fascinating overview of mascots that various ethnic groups claim are offensive. While it states the Warrior images are legal, it also cites case law that school districts are within their legal rights to reject such icons and monikers.

It also reveals that Carpinteria is in the company of schools that refuse to get rid of “Rebels” references and images of the Confederate flag, even though African-American students protest such representations as a result of their connections to slavery. Conversely, the Los Angeles Unified School District eliminated all American Indian mascots in its system in 1997. Carpinterians both in favor of and opposed to the Warrior mascot will no doubt be eagerly awaiting March 17 to find out whether their high school will decide to be like those that cling to their past, regardless of accusations of racism, or those that validate such claims by shedding the contentious icons.