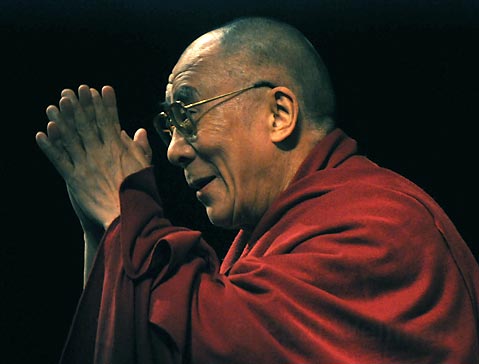

The Dalai Lama Talks Secular Ethics

His Holiness Holds Press Conference, Lecture on Ethics for our Time

After delivering a challenging two-hour lecture on the intricacies of Buddhist philosophy and practice, the Dalai Lama switched gears Friday afternoon, holding a 1 p.m. press conference followed by a public talk on ethics. In both cases, the Tibetan leader spoke in lucid terms about the importance of compassion, values, and dialogue.

“Wherever I go, I always stress the importance of compassion,” he told a group of about 30 assembled journalists. “I consider it the source of strength, and self-confidence.” Throughout the afternoon, the Dalai Lama was clear to distinguish between secular and religious ethics, stating, “Some say there is no God; some say there is God. Big difference, eh? But that is not a problem.” Ethics, he explained to a spellbound crowd of 6,000 during his afternoon lecture, is not a religious matter at all, but rather a matter of achieving a spirit of globalism – of rejecting an “us versus them” mentality, and focusing attention on our inner values. Speaking of his own life, including the loss of his country at the age of 24 and subsequently living for 50 years with little but heartbreaking news of his people’s oppression, the Dalai Lama explained, “During that period, money failed to bring consolation.” His favorite wristwatch, his dogs and cats, even his friends, he said, failed to provide him with inner peace. The key instead was “inner compassion, the spirit of forgiveness, and a realistic attitude.”

The Dalai Lama is known for his sense of humor, including a predisposition for giggling, and despite a mild head cold he was on good form on Friday, laughing when a cell phone went off in the crowd and when his microphone temporarily malfunctioned, and showing boyish delight in the telling of personal anecdotes. In order to illustrate the importance of nurturing young children, the 74-year-old spoke of his own childhood in rural Tibet, where his illiterate, farm-working mother had showered him with affection. “I took advantage of it,” he exclaimed, describing the way he would grab her ears and steer her around the farmyard when she carried him on her shoulders. Eyes wide, he guffawed at his own admission. “I bullied my own mother! But now I have a certain amount of compassion, and it comes from the seed of my mother.”

While such stories – and the lessons they are meant to convey – can be interpreted as proof of the Dalai Lama’s lack of political or intellectual sophistication, they are instead a mark of his ability to leave aside the distractions of scholarship and theory in order to communicate directly the heart of the matter. In this case, the man who has worked and waited for half a century for open and honest dialogue with Beijing spoke of the basis from which he believes justice and peace between nations arises. “A healthy society comes not from government, but from families, from individuals,” he stated, reasoning that since a large portion of humanity today is not particularly religious, “We must find ways and means of reaching these people about the importance of moral ethics.”

Whether his topic was the economic recession, relations between Tibet and the Chinese government, or advice for college students who want to work for social justice, the Dalai Lama pointed out opportunities to practice compassion, tolerance, and realism, suggesting that these in turn could only come from self-knowledge and healthy personal relationships. And though Tibetan Buddhists worldwide consider him the incarnation of the Buddha, though millions look to him for spiritual guidance and wisdom, the Dalai Lama made it clear in his talks that he sees himself as an ordinary monk. “I want to tell you – I am nothing special,” he insisted Friday. “I am just another human being like you.”