A Serpent Strikes

An S.B. Boy’s Harrowing Tale of Being Bitten By a Rattlesnake

On Wednesday, August 5, 2009, at 5:45 p.m. my eight-year-old son, Lucian, was bitten by a rattlesnake. This is what I remember:

A cry, sharp and loud, followed by yells. My boy holds his left leg with hands clasped below his knee, hopping around 15 feet or so from a rattler, coiled, ready to strike.

It is the first day of Fiesta. We’ve driven high into the mountains behind Santa Barbara, atop Gibraltar. My friend brought my two boys and me here for an afternoon. We swim in a cool, moss-green pond, swing from a rope, and eat Farmers Market-fresh strawberries and melon. In the late afternoon, after it has cooled, we go for a tour of the area with a plan to come back to the pond for one last swim before driving back down the mountain.

Lucian walks ahead of us. We climb a small slope to a sun-baked plateau next to an apricot tree. That’s when we hear the scream. A lengthened moment occurs while I put things together, then I ask, “Did you get bit by that snake?”

“Yes,” my friend says, shaking us out of our shock. “He’s been bit.” Time slows, and instinct mixes with remembered bits of knowledge. I remember that rattlesnake bites are rarely lethal, but they are more dangerous for children because their bodies are smaller. We have to get him to the hospital as quickly as possible. My friend is urging us all to the car.

I recall to keep him calm. Keep the heart rate down. He must not walk, not on that leg. I swoop him up, and rush down, padding across a board bridge, my sweet baby in my arms. (I do believe the stories of mothers lifting cars off their children; carrying my son in that moment, he was weightless.)

“Shh,” I say. “It’s going to be okay. You’ve got to stay calm. It’s very important that you relax as much as you can. Breathe,” I say. “Breathe. Slowly.”

My friend drives as I sit in the back and fumble with our seat belts.

“I’m shaking,” Lucian says.

“It’s okay,” I tell him. “Stay calm. Breathe. Slowly.”

He closes his eyes. He is amazingly calm. “What will they do to me at the hospital?” he asks. He’s starting to slur his words. He licks his lips. His mouth is tight, and he talks as if he’s had several shots of Novocain.

“They’ll give you antivenin,” I answer.

“I’m shaking. Why am I shaking all over?”

I’m freaking out watching him tremble, watching his mouth working hard to form the words, thinking he’s reacting very quickly systemically to the venom. But on the outside, I stay calm, and I say the only thing I can, “You’ll be okay, Baby. You’ll be okay.”

“I feel nauseous. It feels like my mouth is filling up with blood,” he says as he touches his cheek, his eyes trying to focus, looking as if he might faint.

He needs help now. I grab my cell phone and dial 911 and arrange a rendezvous with a fire engine just above Fire Station 7.

A fireman gives Lucian oxygen and asks when he was bitten. Ten minutes ago, I answer. He takes a ball point pen and writes on the inside of my son’s left leg, above the bite, just under the bulk of the calf muscle, “Bite @ 5:45 8/5.” That is the time of envenomation. Lucian is so brave. He doesn’t cry or complain. The ambulance arrives, and the EMTs get him onto a gurney for transportation to the hospital. The EMT puts an IV in his hand — morphine for the pain.

The Biting Kind

According to the California Poison Control System (CPCS), rattlesnakes account for more than 800 bites each year in California. Most bites occur between the months of April and October when snakes and humans alike are more active outdoors. Most snake bites happen when the rattlesnake is handled (even when it’s dead) or accidentally touched by someone walking or climbing. About 25 percent of the bites are actually “dry,” meaning they are warning strikes where the snake injects no venom.

In a CPCS press release from April 29, 2009, Dr. Richard F. Clark, executive medical director for the CPCS and director of the Division of Medical Toxicology at UC San Diego stated, “Over the past couple of years, we have seen an increase in powerful snake bites, and patient reactions have become more severe.”

When I started researching rattlesnake bites after my son was out of the hospital, I contacted Dr. Clark. He confirmed that this increase in power of strikes and severity of reactions is the general trend, particularly in southwestern and central parts of California, where the Southern Pacific rattlesnake lives. Experts don’t really know why this is so, but there are a few theories: encroaching development farther into rural areas; a change in the snake’s diet; a potential interbreeding with Mojave rattlesnakes and therefore more neurotoxin in their venom; or perhaps even climate change.

According to the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History’s vertebrate zoologist, Paul Collins, the two species of rattlesnakes that we live with in Santa Barbara County, the Northern Pacific rattlesnake (found in the northern parts of the county and San Luis Obispo) and the Southern Pacific rattlesnake (found in the rest of the county), are not aggressive.

However, Dr. Clark described Southern Pacific rattlesnakes as having “nasty dispositions” and said that they are more inclined than other rattlers to bite before retreat.

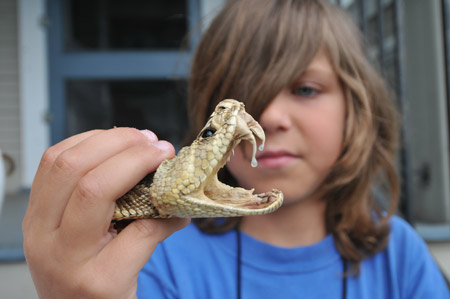

Lucian is not the type to try to catch snakes. He is cautious by nature. He said that he was walking and looking down at the ground, and he didn’t see the snake. He said it was the same color as the dirt. It struck, and then it coiled and rattled.

Rattlesnakes are among the group of snakes called pit vipers because of the small pits located on each side of their heads, temperature sensitive structures that assist the rattlesnake in finding prey, even in the dark. Glands behind their eyes produce the venom that then flows through ducts to the hollow fangs. The fangs are normally folded back against the roof of the snake’s mouth, but when it strikes, the fangs pivot forward to inject the venom, the amount of which can be controlled from either or both of the fangs. After death, a rattlesnake can still inject venom for an hour or more by reflex action, so don’t ever play with rattlesnakes — even dead ones.

The amount of venom injected depends on myriad factors: the time elapsed since the snake’s last bite, the degree of threat the snake feels, the size of the prey. The venom itself is a complex mixture of tissue-destroying enzymes intended to immobilize the next meal and basically digest the animal from the inside out. The common theory is that a bite from a baby is much more serious than a bite from an adult.

When asked about baby rattlers versus adults, Collins said that baby rattlesnakes, in addition to not being able to control the amount of venom they inject, tend to strike more often because their rattles aren’t effective tools for warding off predators. The young rattlers also have a higher neurotoxic (i.e., paralyzing) aspect in their venom. Baby rattlesnakes feed on lizards and so need to immobilize their prey rapidly. On the other hand, baby rattlers make less venom.

Older rattlesnakes produce more venom. Yes, they can control how much is injected, but as with my son, it can be a lot. The older rattlers have a more hemotoxic aspect in their venom, meaning it affects the blood and organs, causing a breakdown and inflammation of the body — again, digesting the prey from the inside out. According to a 2009 Scientific American article, the Southern Pacific rattlesnake’s venom produces more neurotoxins than its cousin, the Northern Pacific rattlesnake.

Waiting for Antivenin

In the emergency room, loads of medical professionals come in and out. They mark Lucian’s leg again, showing the growth of ecchymosis (redness spreading or streaking due to escape of blood into the tissue from ruptured blood vessels). They administer more morphine. He’s in pain. He says it’s more pain than he’s ever felt in his life. Still, he doesn’t cry and remains calm.

It is impossible to know how much actual venom has been injected into my boy. At first, the doctor thinks Lucian has received a minor envenomation, based on the amount of swelling at the site of the bite. Later, when he marks the progression at 7 p.m., he says that it is a moderate envenomation.

An emergency room doctor informs me about antivenin, saying that although there can be side effects — such as serum-sickness or a person’s system rejecting or having an allergic reaction to the antivenin — in Lucian’s case, it is probably worth the risk. The doctor says they will first give him a small sample of antivenin to see how he reacts before giving him the larger dose. Lucian receives an antivenin made from sheep called CroFab. The sheep is injected with venom from rattlesnakes — the Western and Eastern Diamondback, Coral, and Mojave — building up antibodies that are then extracted from the sheep and used as antivenin.

One of the original doctors returns and tells me that they’ve got the antivenin ready, finally. It’s 7:45 p.m., two hours after he was bitten, an hour and a half after arriving at the hospital. (CPCS’s Dr. Clark later told me that as long as the patient receives antivenin within two to four hours after envenomation, there are no adverse effects on recovery.)

Several vials of antivenin will be needed to treat Lucian. For every bag of antivenin used, my son is first given a small dose as a test. If things looks good — meaning he can answer simple questions like what his name is, his birth date, where he is — the drip is increased fivefold and the bag is finished. Hours later, in a morphine-filled sleep, these questions get progressively harder for Lucian to answer. But with each trial drip administered, he passes the tests.

Lucian becomes progressively more restless. He tosses and turns and is extremely uncomfortable. He’s got wires attached to his chest, an IV drip giving him fluids, and an oxygen absorption monitor taped to a finger on his other hand. He wants to turn over. His arm hurts. Lying on his back, he flails his arms, reaching out. Every once in a while, it seems difficult for him to catch his breath. But then he is okay; he breathes steadily again. His hair is soaked with sweat. I feel the heat he emits. His face is red and puffy.

He slurs his words. In fact, it is very difficult to understand him. His mouth tingles and is partially numb. The muscles around his mouth and in his arms and toes twitch. All his muscles move as though they are water rippling under his skin. It is a constant and fast motion. It is unreal to witness, as if observing the concept that a particle can be in two places at once, bumping, colliding, creating a wave, only it isn’t a particle, it’s millions of particles, his muscles, his whole body. This is one of the systemic reactions to the venom, called myokymia or fasciculations. This is a neurological symptom and a telltale sign in Santa Barbara County that the bite was by a Southern Pacific rattlesnake.

They take an X-ray of his chest. They hook up more wires and take an EKG reading.

The sheet beneath him becomes a sweat-soaked tangle that the nurse tries to help him with to keep him comfortable. She calls him Pumpkin.

His mouth is dry; he pushes foam made of spit bubbles out. It’s difficult for him to swallow, the only thing that makes him cry. He wants orange juice. He wants orange juice so badly, but he isn’t allowed food or liquids. The nurse soaks a washcloth and lets him suck on it.

At 10 p.m., Lucian is transferred to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), and his leg is marked again. The doctor tells us Lucian will be given the antivenin every hour and that in the morning he should be feeling lots better and will be able to eat and drink. I tell him this. He cries. Morning is a long way away.

The individual responses or effects from the venom differ among patients because the composition of venom varies among snakes. Symptoms tend to include puncture wounds and pain at the bite site (early and intense pain implies significant envenomation); swelling, or edema; ecchymosis (spreading redness); and blisters. Additionally, laboratory analysis may reveal hematologic abnormalities: coagulopathy and/or thrombocytopenia (affects the ability of the blood to coagulate); local or diffused myotoxicity (the toxic effect of the venom on the muscle, which may result in compartment syndrome, when the pressure within the muscle builds up to dangerous levels and can lead to loss of limb or death); or rhabdomyolysis (the breakdown of muscle fibers with the leakage of potentially toxic cellular components into the systemic circulation, which can include acute renal, or kidney, failure).

The more general systemic effects of a rattlesnake bite may manifest as nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, myokymia/fasciculation (the muscle ripple effect), perioral numbness (tissues around the mouth and the Novocain-like response), and a metallic taste. Severe envenomations may cause respiratory distress, low blood pressure, and/or altered mental status.

The next day, I learned there was concern about my son’s kidneys, as he had started to demonstrate some of the symptoms of rhabdomyolysis. They flushed his system with lots of fluids and inserted a catheter. By mid morning, the scare was over, although I had to get him to continue to drink lots of water and watch the color of his urine for a week or so after our return home as his system continued to process the decomposed muscle. (We were also told that without treatment, this bite would have killed my son. It would have killed an adult — just a little more slowly.)

Lucian’s recovery time took longer than the doctor’s initial estimate. Throughout approximately 20 hours, my son received 28 vials of antivenin, spent two days in PICU and three days in the hospital total, and had three weeks of physical therapy to get him walking again.

Despite his ordeal, he still likes snakes.

Things You Should Know

Rattlesnakes tend to hide in rock crevices, under logs, in heavy brush, or other protected areas. However, they can also be in roads, paths, and out in the open. As my son learned, rattlesnakes are often well camouflaged, making it difficult to see them. Rattlesnakes are not confined to rural areas — they have been found in urban settings such as parks, golf courses, and in gardens. Here is a list of precautions to take compiled from the California Department of Fish and Game, the University of California Integrated Pest Management program (UC IPM), and California Poison Control System:

How to Prevent a Rattlesnake Bite

• Never go barefoot or wear sandals when walking in the rough. Wear clothes that will protect you, such as shoes or boots and long pants.

• Keep children and pets close by when outdoors.

• Learn what rattlesnakes look like. Teach children what they look like. When identifying a rattlesnake, the key characteristic to look for is their distinctive, triangular head shape — nonpoisonous snakes do not have this obvious characteristic. The infamous rattle is a less reliable identifying feature.

• Stick to the paths. Avoid tall grass, weeds, or heavy underbrush.

• Always look for concealed snakes before picking up rocks, sticks, or wood.

• Don’t put your hands where you cannot see, and avoid wandering around in the dark.

• Step on logs and rocks, never over them. Check out stumps or logs before sitting down, and shake out sleeping bags before use.

• Use a walking stick when hiking. If you come across a snake, it can strike the stick instead of you.

• Never grab “sticks” or “branches” while swimming in lakes and rivers. Rattlesnakes are good swimmers and can be mistaken for a stick.

• Be careful when stepping over the doorstep. Snakes like to crawl along the edge of buildings where they are protected.

• Baby rattlesnakes are poisonous and cannot control their venom release, so leave them alone.

• Never hike alone.

• Never handle freshly killed snakes, even a head separated from the body. You may still be bitten.

• Never tease or handle a rattlesnake.

• Teach children to respect snakes and to leave snakes alone.

What to Do if Bitten

• DO stay calm and try to calm the victim.

• DO immobilize the affected area and restrict activity. If the bite is on your arm or leg, create a splint if possible. Too much movement may spread the venom to other parts of your body. Do not run.

• DO keep the bitten area below the level of your heart.

• DO remove watches, rings, clothing, etc., which may constrict swelling.

• DO transport to the nearest medical facility.

What Not to Do if Bitten

• DO NOT make an incision over the bite.

• DO NOT try to suck the venom out with your mouth.

• DO NOT use a tourniquet.

• DO NOT use an ice pack or pack the bite area in ice.

• DO NOT let the victim drink alcohol.

• DO NOT apply electric shock.

• DO NOT attempt to capture or kill the snake. If possible, take a picture of the snake but remember that a snake can strike as far as its own body length, so stay well away from it.

4•1•1

California Poison Control System 24-hour emergency hotline: 800-222-1222; calpoison.org.