From Klunkers to Mountain Bikes

The Real True History

Imagine riding full-speed down mountain fire roads on heavy cruiser bicycles with coaster brakes smoking. It must have been an incredible adrenaline rush. Was it madness, or the beginning of a new sport? Most observers thought — madness.

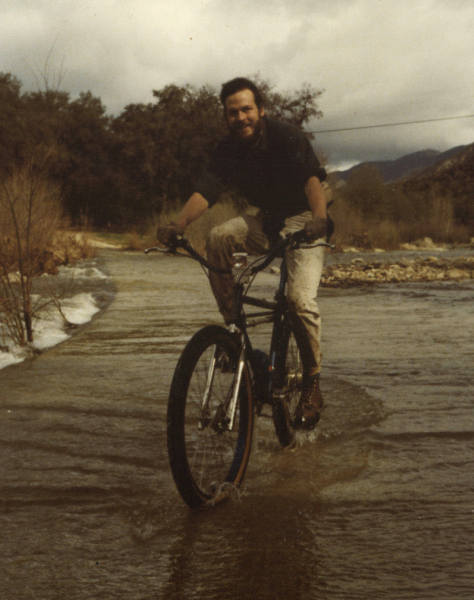

In the early 1970s, young hippie bicycle enthusiasts from Marin County to Los Angeles began riding old Schwinns down mountain trails and fire roads. Many of them called their bikes “klunkers.” These young knuckleheads weren’t trying to build a mountain bike. Like young tinkerers since the dawn of the Industrial Age they were experimenting, playing, seeing what they could build with their hands and minds.

They were backyard garage mechanics, taking a frame from an old cruiser, the derailleur from a road bike, a drum brake from a motorcycle, and combining them with Suntour thumb shifters, motorcycle brake levers, knobby tires — and having fun building something new that made their friends stare in awe. Racing faster downhill was the goal. Fastest was the holy grail. Seeing who could build a better bike was how you won the admiration and respect of your friends.

A golden age is when a technology, art, or sport is at a peak, a period filled with innovation, excitement, energy, growth, turmoil, and constant change. For personal computers the golden age was in the 1970s, when Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and hundreds of other nerds were tinkering in garages and basements — building circuitry, programming in BASIC, and popularizing personal computers. For pop art it was the late ’50s and ’60s, when art, drugs, and rock and roll exploded into the crazy New York scene of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, the Velvet Underground, Exploding Plastic Inevitable events, and Ultra Violet. For mountain biking it was all happening in the 400 miles between Marin and Los Angeles in the 1970s and early 1980s. Each of these movements represented a direct challenge to tradition, though their progenitors did not necessarily know they were taking part in the birth and development of a new technology, art form, or sport.

The early history of mountain biking is a mix of faded newspaper clippings, memorabilia, old newsletters, sketches, and people’s memories of long ago events. Call it the fog of innovation. Heroes emerged, though history books have not fully recognized all the early pioneers. What history there is, is Marin-centric. Gary Fisher and Joe Breeze are far better known than James McLean or Victor Vicente. Marin and Mt. Tamalpais are better known than Santa Barbara and the Santa Monica Mountains.

Dozens of tinkerers contributed to the evolution of a cruiser into a klunker and finally a mountain bike as we ride it today. Craig Mitchell, from Marin, may be the person who deserves the most credit for transforming clunkers into lightweight mountain bikes. But Santa Barbara area innovators like Ken Beach, Mike Celmins, Terry Gearhart, Chris King, James McLean, Chris Pauley, and Victor Vicente made major contributions that helped turn klunkers into true mountain bikes. It’s time to tell the complete story of the local Santa Barbara enthusiasts who helped create the bike and sport as we know it today.

As for the term “mountain bike,” Santa Barbara’s own James McLean is usually not given enough credit. As the story goes, in the late ’70s he was working at Open Air Bicycles in Isla Vista when a hippie from Tepee Village came in with a derailleur-equipped fat-tire bike. The rider’s name was Wing Bamboo, and when James asked him what he called the bike, he responded, “I call it my mountain bike.” James thought that Wing’s bike was cool, but at 50 pounds it was very heavy, and he imagined a chrome moly tube version with lighter weight aluminum components and wheels. Finally, in 1978, he put together a bike based on a lightweight frame and called it his “mountain bike.” Working as a bike sales rep, James went on to spread the name and the gospel of the mountain bike up and down the West Coast.

Many early mountain bike races were run in the Santa Barbara area. In the early ’80s, Victor Vicente of America, McLean, and other riders organized a series of off-road races. Each race featured unique terrain and challenges to test both riders and bikes.

In the winter of 1980, three riders — crazy or dedicated, depending on your point of view — attempted the First Roughneck Ride and Suicide Run in rain, snow, and mud, from New Cuyama to the ocean. None of the brave or foolish riders managed to complete the course on a bike. After that crazy event, the Sespe Hot Spring Two Stage Race featured a 35-mile, two-day out-and-back ride in the rugged terrain of Los Padres National Forest.

Running from Reseda, over the Santa Monica Mountains, and ending at the ocean, Reseda to the Sea started at a time when most people still had no idea what a mountain bike was. It was also one of the first races to attract riders from across the state, including a bunch of Marin riders on state-of-the-art, hand-built mountain bikes. Victor Vicente, of course, rode his unique hand-built Topanga with 20-inch wheels.

The flyer for the first Central Coast Clunker Classic held on June 7, 1980, in San Luis Obispo and sponsored by the Goleta Valley Cycling Club summed up the challenges of the ride. “This is not a ride for the faint of heart or weak of spirit but offers a unique challenge and an incomparable sense of accomplishment,” it read. The 25-mile ride began at Lopez Lake recreation area, and covered 20 miles of unpaved roads and trails, and a 10-mile climb to 2,700 feet.

The So Cal Hill Climb Championship challenge was a 5,700-foot climb to the peak of Mt. Wilson. The Topanga Riders Bulletin notes, “After a couple of hours at the summit either partying in a van with lots of warm bodies or taking care of mechanical matters in the snowflakes, 25 downhillers pointed their bikes back down … ”

And, for the final race in the series, the Santa Monica Mountains Downhill Champs, riders rode down a fire road in Puerco Canyon with a 3,000-foot drop.

There aren’t may off-road riders that wouldn’t recognize these words from one of the early Topanga Riders Bulletin, “ … rising with thumb poised on shift lever … hoping that a drop of that really salty sweat doesn’t run into the eyes … knowing that the scenery is great, focusing attention on the rocks in the road ahead … so what if my freshly oiled chain has gotten so dusty it squeaks … keeping an eye on the tire tracks of the leaders … would give anything to see those hotshots take this insane downhill and I’m sure ready for that cookout tonight and some leisurely backpacking tomorrow!”

Mountain bike racing has become more professional and the equipment increasingly sophisticated over the last 40 years. But I’m sure that creative young riders are right now tinkering in Santa Barbara garages, looking east to the Santa Ynez peaks for inspiration, and dreaming of their lighter, faster mountain bike. Waiting to hear their friends yell, “Wow!”