Driving to the High Country

Searching for Cuyama

CUYAMA RIDE: To the average Santa Barbaran, I suppose, a drive around the county’s entire circumference is of little interest. What’s there to see up there on the county’s northern roof, anyway?

The Cuyama Valley is high, windy, and dry, with less rain than the Sahara Desert. To most of Santa Barbara, it might as well be on the moon.

Cattle outnumber residents. You can no longer get buffalo burgers at the Cuyama Buckhorn (closed) or fuel at New Cuyama’s only service station (closed and out of gas when I visited last weekend). Also shuttered is the Bates Motel–style place attached to the Buckhorn. Its pool is a sick green.

Running past New Cuyama is Highway 166, mostly a high-speed trucker route between the coast and the San Joaquin Valley connecting Santa Maria and Bakersfield.

Yet something makes me want to make the drive every few years, partly to prove to Santa Barbarans that there is a there in Cuyama (Chumash for “clams,” due to millions of petrified clamshell fossils found in the valley) and partly because the late naturalist/condor expert Dick Smith and I used Cuyama as a jumping-off place for backpacking into the backcountry decades ago.

But I was saddened when I arrived, mightily missing the Buckhorn eatery and its bar with mounted animal heads, and area ranchers wetting their whistles with draft beers and telling stories. The nearby Burger Barn and a deli down the street just didn’t cut it for me.

Still, I wanted to see Cuyama again.

Sue and I took the scenic back-road route, over San Marcos Pass, for breakfast at Los Olivos Grocery. We filled up on tacos stuffed with egg, chorizo, bacon, cheese, and hash browns and heaped with salsa, and we gulped plenty of coffee. Who knew when our next meal would come?

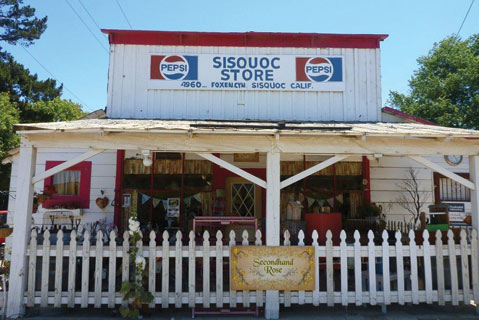

Then we hooked onto winery-studded Foxen Canyon Road. It’s a lovely drive to the field-crops arena of Santa Maria Valley, where we stopped at the old Sisquoc Store. The gas pumps are long gone, and the time-worn general store has turned into Rosemary Ray’s neat, charming Second Hand Rose, full of collectables.

Sisquoc is a scattering of modest homes, a quiet place, but many years ago it was a booming farm town with a wild nightlife. When I stopped in back in the 1980s, then–store owner John Wesley said, “They tell me that in the old days, Sisquoc was a place where people from Santa Barbara would come to fight. They had a dance hall across the street. Politely, we call it a hotel.” Others, he said, would call it “a house of ill repute.”

Things have quieted down a lot. “I’m having a blast,” reported Ray. “The guy I rented from said [the store] was 120 years old.” Up a ways, the old Garey general store is now a deli where you can buy beer and burgers. A sign over the kitchen reads “Gone to Therapy.”

The building harks back to “about 1890, I believe,” said owner Shawn Rees. “We hope it’s here another 120 years.” So do I.

We swung onto Highway 166 at Santa Maria and followed a good road east through hilly country in and out of San Luis Obispo County. Just to the north is the huge Carrizo Plain National Monument. To the south run the Sierra Madre Mountains and designated wilderness areas. Dick and I used to drive up Santa Barbara Canyon, chat with rancher Gertrude Reyes, and then head up to the high potrero country.

New Cuyama, 2,150 feet above sea level, was born when oil was discovered there in 1949, and Atlantic Richfield built a town, complete with schools, an airport, and rows of single-family homes.

The oil and gas are about played out and the “pearl of eastern Santa Barbara County,” as it was once known, has lost its luster. The 2010 census put the population at 517.

Then we turned for home, south on Highway 33, cutting through Ventura County, stopping at Santa Barbara Pistachio for $6 bags of organic nuts, and following the winding road to Ojai. Tasty burgers and coffee at the Ojai Valley Inn & Spa fueled us for the remainder of the day-long, 230-mile trek.

As for New Cuyama, I recalled what Buckhorn manager Ron Record told me in 1989, marveling over the wide open spaces and yearning for a pipeline full of state water. “If we had water, we could turn this into Palm Springs.”

Maybe next year.