Winner’s Circle

Olympic Gold of Another Kind

“Mom, I don’t care if I win; I just want to prove that I can participate.” Stephanie grinds her boot heels in the sand as she turns and marches toward her horse. The gelding looks enormous. The upcoming event: Bareback, intermediate. My young daughter gets a leg up. I twist my knuckles while she appears to be calm, taking the reins in both hands, with big black Satinas under control.

Stephanie holds the reins perfectly, yet I wonder why she is using both hands when the instructors know that her right hand is partially paralyzed. Then I notice knots on the right rein and realize they are an aid to her hand. I am now glad that I haven’t meddled; Elaine Kay, Santa Barbara’s Therapeutic Riding Academy’s founder and instructor, knows exactly what she’s doing.

Earlier, hundreds of colorful balloons had been released into a blue sky, swept free of smog by California’s erratic spring winds. The atmosphere in Riverside, where the equestrian Special Olympics are being held, is festive. The early morning air is crisp, filled with the grassy smell of alfalfa, the sweet and slightly pungent odor of hay, and the unmistakable whiff coming from the sweat and manure of horses. Stephanie inhales deeply, loving each trace of horse-related odors.

Seeing my daughter with the other participants, who have varying degrees of handicaps, jolted me back to my reality, when years ago illness had stolen part of my child. She was a healthy and bright 7-year-old, when mosquitoes dined on her blood in Acapulco. A week later, she fell into a six-week coma. Her favorite animal, the horse, had been the vector for the virus of this exotic-sounding disease, Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Later, Stephanie, with a grave mien, would tell strangers when explaining her paralyzed hand, “I almost died, you know. Ninety-five percent of the people die from my illness.”

Residual scars nested in part of her brain, and there was much she would not be able to do. Going back to her old school was only one of them. But Stephanie emphasized all of the things she could do. Her speech had come back after a year. She could again swim and do her otter backflips, and later she began to ride horses. She took ballet lessons again, even though always in the beginners class.

Despite my being grateful for her positive aspects, seeing her as handicapped was painful. And at a glance, she did not seem to fit in. But appearances were deceiving — within her brain lurked scars, which led to intermittent seizures, some of them terrifying grand mal. These were held in check by medication, but like the sword of Damocles hanging over her, they would at times reappear, despite her meds. Her handicaps were numerous, if not easily visible. She had no sense of direction and could not find a bathroom in a restaurant. She had lost her short-term memory, and her spatial disorientation was grave, which in turn affected her balance. But not on a horse.

My eyes return to Stephanie, who appears happy, high on her horse. I watch her pat the horse’s withers, lean over the sleek neck, and whisper into his twitching ear. Her love of horses is touching. I’m thinking of the irony of it. Horses and the cause of her illness.

Stephanie looks self-assured; she handles this horse with ease, and I believe that commanding such an animal gives her a sense of self-worth. Satinas obeys the slightest turn of her hand. How freeing this must be for her, when in real life, she is always told what to do.

I had come along reluctantly. On our long drive to Riverside, my thoughts were negative about the Special Olympics. I thought they are nothing more than making the participants and their parents feel important in a recreational sort of way. I felt the effort and the money might be spent more wisely on something else.

Slowly, as I watch the events, I become emotionally involved. A few of the released balloons have become tangled in trees, and I see a small boy with Down syndrome point to a red balloon among the branches and break out in giggles, sparks of happiness flying from his rounded face. I see riders with varying degrees of physical dysfunctions limping or walking to their events, but all of them are wearing smiles on their expectant faces. I become aware of the bodies of riders, some of which are sadly twisted by cerebral palsy. These children are grabbing manes and mounting their horses. An inner glow seems to radiate from them, and I wonder, how can it be that they are all this happy? How can the judges be fair when so many varying degrees of disabilities are involved?

I slowly begin to realize this is more than recreation. More than a competition and winning a prize. More. So much more.

Stephanie enters the arena. The announcer’s voice boomed through the handheld loudspeaker: “Riders in the blue ring, turn your horses.”

She responds with alertness. I feel a wave of pride. Her seat is good. Her back is flat and straight. She holds her legs well, knees pressed into the flanks of the horse, heels down. Horse and rider walk around the ring in one direction, turn, then walk in the other. Then horse and rider trot, not easy when the feet dangle without stirrups. A slow controlled canter follows, which looks easier, like sitting in a rocking chair. The horses again walk. Stephanie and her horse are calm. I am wondering, who is teaching whom to be so cool and collected? Is it Satinas, the old veteran of the polo field, or is it Stephanie, whose hands are transmitting her attitude?

Winning no longer matters. Stephanie has proved to herself that she doesn’t panic, that she is able to compete. The last command: “Walk your horses and come to a halt facing the judges!”

Stephanie turns, walks, stops. Seconds tick away. My heart pounds. Satinas shakes his head; Stephanie is patting him, then resumes her stance, reins in both hands. The name of the fifth-place winner is announced. A young man. He leaves the arena beaming. The fourth. My heart beats like a hammering clock. The third, the bronze medal. Surely she was good enough to win third? In my anxiety I had not taken count of the number of participants in Stephanie’s group. Now they announce the silver medal. My heart is a loud thump in my throat. My mind is clouded, and I have no logic left.

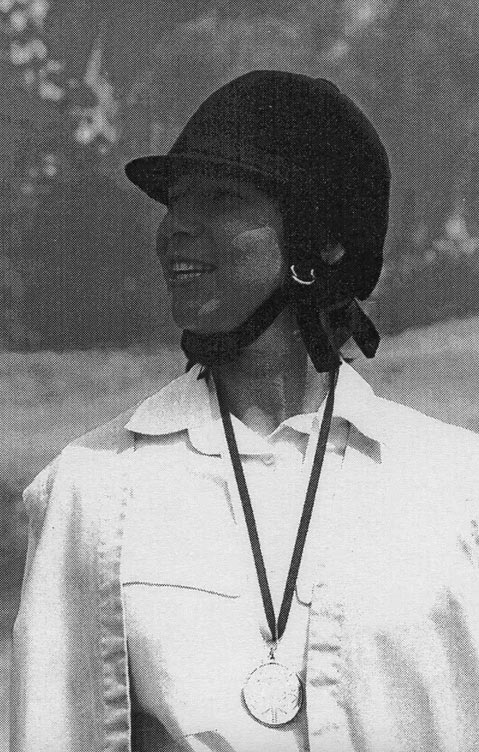

And then, “The first prize, the gold medal goes to Number 60.” What? That’s her number! An unbelievable feeling rushes through me; I strain to hear what the announcer says, “Miss Stephanie Finell of Santa Barbara!”

“Yippee!” I scream. I throw my straw hat into the air and grab a Kleenex. I look at my daughter and see that she, too, is weeping. Stephanie bends low over Satinas’s head as the judge hangs the gold medal around her neck. I see her wipe her eyes with the back of her hand and strain to hear her answer the judge, whose question I had not understood.

“Me?” she said, “Cry? Because I’ve never won anything … ” Her voice sounds muffled as she continues, “I’ve never achieved anything before.”

That’s it. Suddenly I understand. This is the purpose of the Special Olympics — to give these handicapped people a rare sense of accomplishment. For this short time, could winning the “real” Olympic gold be any more exciting? I glance at my daughter, wiping her eyes while holding on to the reins. Trumpets are blaring, announcing the upcoming event. Stephanie is turning her horse and exiting the arena, her face lit with joy, while the gold medal on her chest catches a beam of sun, reflecting as golden sparks in her brown eyes.