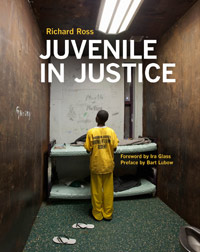

Juvenile in Justice

Photographer Richard Ross Documents and Fights for Kids Behind Bars

Richard Ross has a bad back but a big heart. Since 2005, he’s talked to more than 1,000 young people in over 200 juvenile detention facilities, sitting for countless hours in their cells on uncomfortable concrete floors. A photojournalist published in the New York Times and Vogue and a UCSB art professor who’s shown at the Tate Modern and The Getty, Ross’s latest book project — called Juvenile in Justice and released earlier this year — dives into the disquieting world of 70,000 kids who spend any given night behind bars in America.

The images are a call for attention and compassion, as Ross found that most of his subjects are simply troubled teens from broken homes, locked up for petty crimes but then often flushed into an unforgiving justice system focused on punishment rather than rehabilitation. Though Ross admitted that some of the youth he spoke with committed serious felonies worthy of their sentences, the vast majority suffer from the criminalization of normal adolescent shenanigans, he said, a product of political posturing and the unbalanced allotment of state and federal money to more cops and lockups rather than schools and programs.

“It’s an incredibly complex ball of yarn,” said Ross during our interview in his living room on the Mesa earlier this month. “But you can’t get too frustrated, and you can’t manifest frustration by ranting.” To that end, Ross has become an artist/advocate, delivering talks around the country about what he sees as a broken juvenile justice system and providing the 150 or so photos from his book to nonprofits, research institutions, and activist groups free of charge. The kids’ faces are obscured and their full names withheld for legal reasons.

During our interview, Ross spoke about how he chose subjects, the challenges he faced during the work, and why he’ll never be able to tear himself away from it.

In 2006, you asked a juvenile prosecutor if he ever thought a system would be so successful at reformation that his job would be eliminated, and he responded, “I will be here as long as the state of Texas keeps making 10-year-olds.” Was this the lightbulb moment for you? You know, there’s never a natural lightbulb but a moment that gives you the impetus to go back and see what you’ve been doing. When you find something like this, you start researching it more and more, then just keep thinking, “This can’t be right.” I’m not a trained sociologist or criminologist, but to me, these kids are being ignored as societal detritus and just dismissed because of economic deprivation, lack of opportunity, lack of expectation, and the color of their skin.

I don’t use these photographs to say the whole system is fucked and totally unapproachable. I hope to find a piece of the puzzle we can work on and correct so there’s more helping kids in neighborhoods instead of putting them into detention centers. Economically, it doesn’t make sense to put the majority of these kids in detention. Once they’re brought into the system on petty charges like truancy or curfew violations, they don’t respond to authority the way people would like and get in trouble for violating policies. And the cycle continues.

What do you think about the idea of restorative justice? Thank God we have a school superintendent who listens to advocates like UCSB professor Victor Rios and realizes it doesn’t do any good to kick kids out of school, because they’re still part of society, and otherwise you’re stigmatizing them and making it worse. When you have a zero-tolerance policy, you don’t have restorative justice. It doesn’t work.

the night before, so they have taken away privileges of TVs, cards, and dominoes.

Which programs in town do you think are or aren’t working? I was recently down at the Santa Barbara Police Department with the Gang Suppression Task Force. The sergeant in charge was wearing all black and a bulletproof vest that says he’s with the gang unit. How accessible is he to a kid? Instead of using the word gang, you can reframe the conversation. I’m a gang member — I could have NPR and Ira Glass [who wrote the foreword for my book] tattooed across my chest. We’re all affiliated with something that we care about. The kids they pick up happen to be affiliated with behavior that they don’t like. Instead of offering alternatives, they’re trying to change behavior with suppression. If you deal with these kids with some degree of respect and dignity, you can change behavior much more effectively.

Are you familiar with Los Prietos Boys Camp, and what’s been your experience with Santa Barbara County authorities? Yeah, I’m dealing with the probation department, and they wheel Los Prietos people out as their really good examples of reformation. But they won’t let me in the Santa Maria juvenile detention center. Santa Barbara is one of the the worst counties in terms of allowing me access. It’s been a battle, and part of the battle is dealing with local people who will just shine you on. It’s been endless delays. I’ve seen this in Montana and some of it in the South, but I didn’t expect to see it in Santa Barbara.

I’ve been a university professor for 33 years, and this is my research, and it’s inexcusable. In Harris County, Texas, the director of a facility, who oversees 1,500 people, said, “I’ll have anybody you want talk to you. We want you to see and photograph everything because we’re happy you’re doing this work — we want you to see the good, the bad, and the ugly.” The bad part was going around with him for four days listening to country-western music. And he smoked big cigars.

Which states were most open to you? Weirdly, places like Florida, Missouri, and Texas are very open, but state and local administrations vary, so inroads you make in one place can disappear in another. I always explain that my work is to add some recognition to the people behind these statistics, and that means I will do anything and everything to protect the kid. The institution can come under criticism for letting me in, but I’ll give them images and administrators can say, “This is what’s going on; this is where we need resources to change structure and procedure.”

Is there anyone you won’t give your pictures to? One image went to an evangelical magazine. I’m totally atheistic and cynical and New York, but when I hear from organizations that are evangelical, either Christian, or Muslim … what do I do? I went to one facility in central Pennsylvania, and about 85 out of 90 kids were Muslim. There you have the Qur’an giving them structure where their lives maybe didn’t have structure before. Am I going to be someone to judge that this is improper? Because a lot of these kids are Muslims of opportunity rather than true believers? How do I judge that? And if the Imam wants images to show what they’re doing, do I have the right to make a decision and say, this is not what I feel? These are issues that an artist frequently doesn’t have, so I’m learning new territory, and it’s pretty fascinating but also a responsibility that frightens me.

Have you done social-justice work on this scale before? No, but everything has brought me to this point. Dealing with the bomb shelters in my book Waiting for the End of the World helped me learn how to gain access to a population that’s very secretive and closed off. I had to learn to sit down and listen to people, learn how to be a reporter, speak to people with respect. When I did a project with my daughter of photographing her every day of high school, I had to figure out how to talk to teenagers.

Talk about some of the aesthetic and editorial choices you made for Juvenile in Justice. I decided to put all the captions in first person rather than third person to give these kids more voice. It was a big breakthrough. I took notes, just listened to them. I would go to these places all day, then go to a cheap hotel room and transcribe notes ’til 2 or 3 in the morning. I did this for five or six years and didn’t tell anyone about it. I knew that if people in this world started knowing about it, I would be burning bridges in front of me. So I had to keep it quiet. When I started looking for a publisher, I couldn’t get anyone. Sometimes people would say, “We’re really interested, our editorial board cried when they saw the images, but we can’t publish it.”

Because …? Because books on social activism don’t make money. And I would ask, “Do you have a mission beyond that?” I don’t fault them, because they’re trying to stay in business, but places like UC Press dismissed it very quickly. I said, “Don’t you have some kind of mission here that goes beyond trying to make money?” At the end of the day, I couldn’t get too pissed off, and I would do what I needed to do.

What kind of equipment did you use? One camera. No flash. Everything was as simple as possible. I really had to be low-key and inconspicuous. The more I brought in, the more difficult it was and the more suspect I was.

How do you approach the kids? Did you have a standard line or question? I would usually explain what I’m doing. I would tell them I’m going around the country and trying to get a good picture of who’s doing what and why. They would ask what’s the worst place, what’s the best place. They’re bored, they’re teenagers, they’re drama queens and kings. I would try and engage them on any level. I’ve photographed in Iraq, in Guantánamo, the Laker Girls tryouts. I’ve traveled all over, I’ve got kids — I’d find something.

How often were you shut down right off the bat? Rarely.

They’re probably craving someone to talk to. Yeah, they’re totally bored. A lot of them are locked down for 23 hours a day. They’re happy if someone comes in and expresses an interest in who they are, especially a male figure that tells them, “I’m here to listen, but you can stop whenever you want. Anything you don’t want to talk about, just say pass.” I would usually ask, “Who comes to visit you?” Invariably it’s their mother or grandmother. I had to be very careful to not talk about anything that was pre-adjudicated so that I couldn’t be deposed. In some cases, like in Florida, they would make me an officer of the court.

What were some of the physical sensations you experienced in these facilities? Cold, claustrophobia. Frequently, temperature is used as a weapon. In Miami, they kept the isolation rooms at about 59 degrees. And in their isolation rooms, which are horrific, the kids are in there with no books, no TV, no cards, no dominoes, no writing utensils, nothing. No blankets, no mattresses, no pillows. It’s brutalist architecture. You define brutalist architecture by concrete, which is the material of choice in most of these places.

But it varies from state to state, county to county. You go to some places, and they’re like dorms with a big carpeted day room. They treat kids differently than adults. I went to Santa Cruz, which is a JDAI (Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative) site where they try to deter kids from going into the system. Santa Barbara is not a JDAI site. It’s something that you volunteer to do, and it’s really spreading significantly across the country, this change in attitude towards juveniles.

Did you ever fear for your safety? Never, ever. Individually there’s no kid that will be a threat to you. The vast majority are normal kids — they’re not psychopaths. When kids get together on Friday or Saturday and they’ve had some weed and some alcohol and they’re in a group, then they become something different.

In all your conversations with experts and advocates, what do they say are the pragmatic baby steps toward improvement? Putting the resources back into the communities. That’s what makes sense. Somehow forming it so that when a kid wakes up, he or she is aware of their own presence and feels like, “I can do something with my life,” instead of a cradle-to-prison pipeline or a school-to-prison pipeline. The idea that they can sit at a normal table, have three meals a day, have a parent that’s capable of looking at homework. Really, fostering a culture of expectation. We have to move away from the criminalization of normal adolescent behavior, throwing them into special education for behavioral issues rather than developmental issues. People don’t wake up one day and decide to be criminals. They start somewhere, and you have ample opportunity to divert these kids from the system. People need to say, as a community, we’re not going to stand for this anymore.

How do you see yourself eventually moving on from this project? I don’t. I think this is an issue that needs a lot more awareness. I’m really grateful for the people who recognize the need for the still image as witness and testimony. So I keep on providing it. I need to keep the images going, alive and fresh. And I’d really like to work more in Santa Barbara, to deal in-depth with some of these kids and look at them once they’re out.

I love my wife and kids; I adore what I’m doing. But the highlight of my life is sitting on the floor of cells and listening to these kids and realizing that I’m 65 years old and I’ve got these teenagers telling me who they are and sharing their lives with me. It doesn’t get better than this.

Here are a few of the facts featured in Richard Ross’s book. He plucked them from a variety of accredited studies, articles, and news reports.

• Juvenile courts in the U.S. annually process an estimated 1.7 million cases of youth charged with delinquency offense – approximately 4,600 delinquency cases per day.

• The cost for a typical stay in a juvenile facility is $66,000-$88,000 to incarcerate a young person for 9-12 months.

• Two-thirds of males and three-quarters of females in the juvenile justice system meet the criteria for one or more psychiatric disorders.

• Despite the pervasiveness of substance abuse, 42 percent of youth residing in juvenile corrections facilities do not receive any substance-abuse treatment.

• At virtually every stage of the juvenile justice process, youth of color — Latinos and African Americans, particularly — receive harsher treatment than their white counterparts, even when they enter the justice system with identical charges and offending histories.

4•1•1

Richard Ross will hold a book-signing at Left Coast Books in Goleta on Saturday, November 3, from 6-9 p.m. Be sure to check out more Juvenile in Justice photos and responses to them at juvenile-in-justice.com and on Facebook.