Brave New Elections

Demographics and Direct Democracy

I tan pretty well but I’m white. I spent two and a half years in Hawaii while serving in the U.S. Army in the early 1990s. Hawaii was then, and is now, a state where whites are a minority. It wasn’t a big deal. Then I moved to California, where I’ve lived for 18 years, a state where whites are also now a minority and Spanish is an unofficial second language. It’s not a big deal.

So when I see that non-whites are increasingly shaping national and local political outcomes I’m not threatened. Because I’m a progressive, I actually embrace this shift. But non-progressives should also accept that racial and ethnic shifts, and power changes along with these shifts, are to be expected in any real democracy that lives up to the “one person, one vote” ideal.

As anyone paying attention has surely learned by now: Mitt Romney lost an election which should have been winnable due to ongoing economic malaise, because of demographics. Minority turnout actually increased over 2008 and minorities are an ever-increasing part of the electorate. Romney’s voters were 88% white, 6% Latino, and only 2% Black and Asian. Obama voters were 56% white, 24% Black, 14% Latino and 4% Asian. The fastest growing minority group is now Asians, and this group overwhelmingly voted for President Obama – as did Latinos and Blacks.

It’s important to look at historical trends in order to provide context for what just happened. Minority voters made up 28% of those who voted in 2012, up from 26% in 2008 and about 14% in 1988. Obama won 80% of these voters in both of his elections, providing a substantial edge in the national race in terms of the popular vote, but more importantly, because of our strange and archaic Electoral College system of electing the president, a huge advantage over Romney. The final tally was 332 Obama to 206 Romney, a whopping 24% advantage for Obama, compared to only a 3% edge in the popular vote.

(This gives rise to a prediction I’m willing to make: by 2020, the United States will switch to a popular vote system for electing the president, and I predict it will be a coalition of conservatives and progressives who make this happen, driven for conservatives by a desire to remain relevant in presidential races and for progressives by a desire for better democracy.)

At the same time as minorities are becoming increasingly politically active, young people are turning out to vote in ever-increasing numbers. And the young’uns also overwhelmingly vote Democratic.

I’m dumbfounded by some of the conservative commentary on why Romney lost this race, typified by Bill O’Reilly’s (far from the most caustic of conservative commentators today) statement: “It’s not a traditional America anymore. People want stuff. They want things. And who is going to give them things? President Obama.”

This statement is incredibly demeaning to literally half of America and it’s simply wrong. Of course, O’Reilly is right about one thing: It’s not a traditional America anymore. What he and other conservatives apparently fail to recognize is that the shift away from traditional America – if we define “traditional” as white-centric political and economic power – is inevitable and positive. We are a nation of immigrants (on a personal note, I’m an immigrant from the UK, having moved here with my family when I was nine years old), many of whom are increasingly not white.

O’Reilly’s comments about the electorate wanting “stuff” misses the far more valid picture about the majority of the electorate wanting to level the playing field through better policies – not to tilt it unfairly in the favor of minorities, as was the case with whites for far too long.

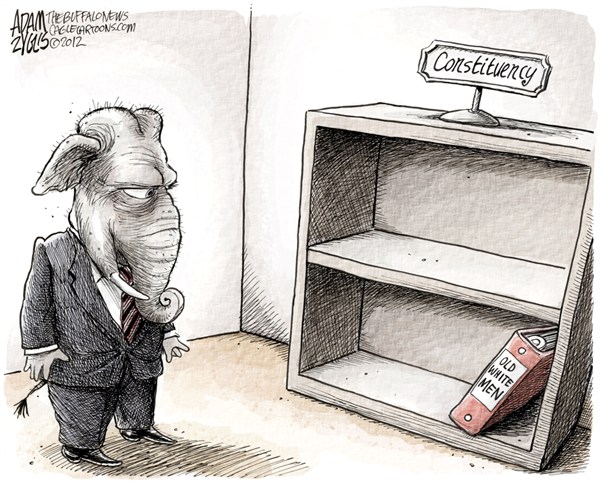

The most on-point comment I’ve seen so far from conservatives comes from Mark McKinnon, a former adviser to President George W. Bush: “Trying to increase the share of a shrinking, dying demographic — old white men — is not a winning strategy. The GOP has to recognize that demographics is destiny in politics. Time to wake up and smell the coffee.” Right.

The second major trend I want to highlight, which is arguably more important than the demographic trends discussed above, is the growth in direct democracy throughout the nation. Direct democracy today comes generally in three forms: initiatives (also known as propositions), which allow the electorate to vote directly on a proposed law; referendums, which allow the electorate to reject a law already adopted by the legislature or to approve a constitutional amendment already approved by the legislature; and a recall vote, which allows the electorate to fire an elected official.

Fully half of the states now allow initiatives of some kind and these are increasingly being used to decide major issues. What used to a crazy Western-state idea – the people directly voting on laws – is now becoming mainstream throughout the country.

Most historically, three states approved gay marriage through popular ballot measures in 2012: Maine, Maryland, and Washington. This was a first in the United States, where states that previously have allowed gay marriage have done so through judicial or legislative action. It seems to me that social issues like gay marriage, abortion, drug legalization, etc., are issues particularly suitable for a popular vote. Amazingly, California is not on the list of nine states that now have legalized gay marriage. We’re losing our bleeding-edge image.

Ballot measures in many states are increasingly being used to decide key political issues – as should be the case in real democracies. A number of other states also passed referenda against implementation of Obamacare. I’m inclined to view this, too, as a positive development because I am generally a states rights’ kind of guy: Power should be devolved (localized) as much as possible given other considerations. Whether health care is properly a national issue is a topic for another essay.

This is the real story in terms of the longer arc of history: Direct democracy is on the rise, and with it – eventually – better democracies overall.

California has long been criticized for its ongoing experiment in direct democracy through ballot measures because of a disconnect between what people want as public goods and what they’re willing to pay for government more generally. The cure, however, for the problems of direct democracy is more direct democracy, not less. A key problem with California’s system is that so many signatures are required to qualify for the ballot that only well-financed efforts can qualify.

This leaves the process open primarily to major corporations, wealthy individuals, or unions. Direct democracy can be further democratized by reducing the barriers to entry in terms of the cash required, allowing instead good ideas to fend their own way. Finland, for example, is pioneering a non-corruptible (or at least less corruptible) model of direct legislative democracy through its new online ballot-measure voting system. The new Open Ministry allows literally any Finnish citizen to propose legislation. If the proposal gets 50,000 online or paper votes (whether in favor or against) within six months it must be voted on by the Finnish parliament, the Eduskunta.

There is no reason why the next step in this online experiment won’t be to allow citizens to vote on implementation of the laws themselves, with appropriate judicial review, as is the case with ballot measures historically.

I’ve written previously about “wiki democracy,” which I define as the evolution of direct democracy through modern technology like the Internet and mobile computing. The rise of traditional direct democracy in the United States, and the increased tendency to put major issues to the people for a vote, is a key first step in implementing wiki democracy. And this is the bigger wave of history that is now rolling over us.

This wave will take us from a strange system of democracy where voters occasionally check in on politicians by voting them in or out of office, but moneyed interests really hold sway in most aspects of political life, to a system where voters are daily participants in governance on a wide variety of issues and moneyed interests have much less influence.

In other words, what is arguably more a plutocratic system than a democratic system will, over time, become truly democratic. More to come on this exciting trend.