Madulce Camp Water-Madness

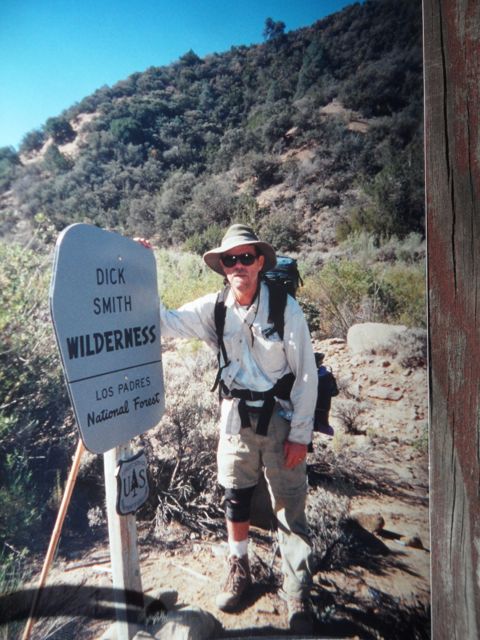

A Dick Smith Wilderness Backpack

Name of hike: Madulce Camp

Mileage: 14-mile moderate backpack roundtrip, with additional dayhike from Madulce Camp to Upper Bear Camp or to Big Pine Mountain. Suitable for sturdy children over 11 or 12.

Suggested time: 4-day backpack.

Map: use B. Conant’s 2012 revised ed. of Matilija & Dick Smith Wilderness; although Conant’s earlier 2008 ed. also works. Park your vehicle at Willow Flat (next to Cox Flat at end of Santa Barbara Canyon Rd.)

The Madulce Camp-Big Pine Mountain trek is another in a series of “disaster hikes” which I’ve somehow managed to scratch through safely. (For two others in this series, see Sisquoc River Scramble and 39 Mile Mission Pine Ridge Backpack.

When my son Gabe was 20, and had spent two years at UCSD, he admitted I seemed to be getting a little smarter as he grew older, although to him I’m still a geriatric oddity at best. None of his friends’ dads spend 40 nights a year in the backcountry, build wilderness altars hither and yon, or spend week-long solitary solo backpacks in Nature. Nonetheless, home on summer break, he wants to make a four-day venture into the Dick Smith Wilderness in the remote, inland portions of Santa Barbara County. We’ll climb to the top of our highest local peak, 6800-foot Big Pine Mountain, the high point of the transverse San Rafael Mountains chain.

I reminded him this was August, and the Taoists tell us that plenty of nature is solar, hot, yang, and male, though an awful lot is also dark, moist, yin, and female, in their terms. Unless we orient ourselves ritually to The Mother back there — call her Gaia or Mother Momoy, Mother Mary or Asherah, Eve, Mother Mira, Saraswati, Mary, or Persephone — we could find ourselves in deep dry caca. I wasn’t jesting at all about the dry part, it being August and all.

The entire outdoor venture ultimately depends on getting to the water source at 5000-foot Madulce Camp. Yes, we had my wilderness experience, Gabe’s great energy, the old red Ray Ford San Rafael Wilderness Map, mucho excellent gear, our solid relationship – these all matter. But it’s way dry back there on the edge of that little Cuyama “badlands” desert area off of Highway 166, the loneliest road in America. There are no rivers, except the Sisquoc, and we won’t aim that far on this audacious backpack.

And so off we went on a summer’s day into baking eastern Santa Barbara County, praying for water every step of the 14 miles, looking around for traces and watercourses wherever they may be. It’s the watercourse way for us! Not every spring is on the map, and not every mapped spring is actually oozing from Mother Earth’s topographic body in August. This earth we westerners ride over roughshod in our careless imperialistic style really is our mother. If we pay her appropriate heed and respect, she may help us out.

Backpacking up Santa Barbara Canyon, after driving around 150 miles from the City of Santa Barbara, we find the obvious trailhead near Willow Flat (Cox Flat) at the end of Santa Barbara Canyon Road. The backpack is easy at first, as it goes along a long-abandoned service road and passes the nearly obliterated Willow Camp, but after a few miles it turns into a narrow defile. This August, even the usually wet Chokecherry Creek is done; stone dry. The yin has receded deeper into her below-surface fastnesses, as the Taoists warned. We each carry four liters of water, so we aren’t overly concerned as we hike steadily on with our heavy backpacks.

Trail conditions are what we expected: badly overgrown, a few red Indian paintbrush flowers, but mostly a mix of hard and soft chaparral plants, with an abundance of fierce, prickly ones like the scrub oaks, manzanitas, willows, and the chokecherry, which seems like a wild rose ancestor replete with vicious thorns that rip at our shirtsleeves like locals angry that tourists have arrived. I usually hike in shorts, but on this high summer trek, despite the growing heat, I choose long pants and a heavy long-sleeved shirt. I am pretty sure the temperature will reach 100 F today.

Gabe and I are counting on the cooling and hydrating power of natural, “feminine,” springs spurting from The Mother’s gorgeous – if dry – body. I’ve carefully checked my written sources, like Gagnon and Ford. They suggest that the three crucial springs will likely be flowing. Supposedly, I can locate them all, since I’ve been here before with my guru, Franko. But it is August, and in July we had the usual heat wave.

Trust your own experience, of course. Gabe and I have made many summer backpacks in the high Sierra, above Convict Lake, above Bishop Pass, up along Mono Pass, Hungry Packer Lake, and so on. But summers we don’t pack locally — it’s just too hot — and Gaia might frown on such overweening hubris. However, the Chumash fled through these parts after their courageous 1824 revolt against the Mission padres; how could a modern anglo fail to try a similar trip? (We will not go into the horrible Don Victor Valley, however.)

The dependable Sisquoc River is about 16 miles away, over the imposing Madulce Ridge, which at 6500 feet is a kind of eastern extension of the Sierra Madre Range. I think about the sacred triad of springs coming up. Here’s the order we’ll encounter them (with approximate backpacking miles):

Madulce Spring (beside first night’s camp of same name) — 7 miles

Upper Bear Spring —13 miles (6 miles on past Madulce Camp)

Big Pine Camp spring — Another 3.8 miles on, up the Buckhorn Road

After about 6.5 miles, we finally clamber up the 900-foot ascent that Conant’s map without exaggeration calls “Heartbreak Hill” – wondering why the Forest Service would gouge out and maintain such an ugly, vertical cut without switchbacks.` We have seen neither water nor traces of water over six miles now, and it feels higher and drier up here at 5000 feet. The intermittent creek coming out of Chokecherry Canyon has receded completely underground, and the trail narrowed dramatically on the way to the base of Heartbreak Hill.

Madulce Camp itself, along Pine Creek, is a gorgeous, sylvan paradise shaded by tall pines, firs, oaks, and ancient cedar trees. We could see the damage from the 2007 Zaca Fire in this area. The mighty oaks are a treat all by themselves, and the ground animals live on the generously spread layer of their acorns.

The historic Madulce Guard Station (cabin) from the 1880s (rebuilt in 1929) was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 – but it’s gone, burnt down by a lunatic in 1999. The corral is still good, as well as the U.S. Forest Service’s tiny tin shack. We call it “Hanta Shack” due to the epic quantity of mouse and rat feces drying on the odoriferous floor. Since hanta virus is airborne (dried mouse/rat pellets can give it off), never go into this ridiculous building. But the corral and shack are 200 yards from the fine camping spot we have beneath the trees, the trail camp, right next to a plantation of ferns.

We straggle into Maldulce Camp at about 11 a.m., two very tired, absolutely parched backpackers finally ready to set up camp and settle into their tents for a siesta during the afternoon heat.

Oh yes, there has been a problem over the last few frantic hours: No water.

Woe is me, the archaic man whose middle-aged back needs rest and rehab after a very scratchy seven-mile backpack topped off with the nearly vertical Heartbreak Hill. Before we rest, we need to drink water, immediately! But no, there’s no water at the supposedly “reliable” Madulce Spring (i.e. Pine Creek). Oh well, nothing daunted, we downed packs and immediately dayhiked up tomorrow’s planned ascent, Madulce Ridge, seeking out water. Our Mother would never fail us! We sped on for 1.5 miles, constantly tantalized, even finding moisture but not nearly enough for pools to scoop from.

Together we had only Gabe’s last liter-bottle, about two-thirds full. It’s another likely “disaster hike,” ill-conceived by Gabe and ill-planned by Dan: It’s August!

We bushwhacked and we scrambled. We checked into numerous “swimming holes” in the dry rocks (they will be full in April), but nada. I scrambled right into one section of the deep creek-bed and followed some bear tracks, getting very dusty/dirty/distracted/disturbed/cobwebby and — even more thirsty. When we got back to our packs at Madulce after the extra three-mile scramble, we split up and gave the local area by our camp much closer scrutiny.

Searching to the north of camp, around the massive fern field, a sure sign of a spring being here someplace, we just can’t find an opening, a vein, to vent a few precious liters of Mother Momoy’s finest liquid into our canteens.

We divided the last of the water. It’s early afternoon, hottest part of the day, and it’ll remain hot until 7:30 at least, back here on the edge of the Cuyama. Oh, land of little rain, the Cuyama [koo-yá-ma], as they say back here. (And who can forget the late great Buckhorn Café? I keep coming back.)

The nearest water is at Upper Bear Camp, another steep six-mile backpack over the rugged Madulce Ridge; it’s the only trail. (We don’t want the Don Victor-Mono Alamar Trail.) I’m not quite sure it’s possible for me to backpack back to the truck today, same day I walked in. And I simply can’t face abandoning my gear, although I’ve had to hide my stuff in a tree before, then fetch it again in a week or two.

I’m rehearsing the situation with Gabe, and we jaw about it some. (This son of mine is laconic as always. Mostly he’s a musician, and he lugs the trail guitar with him like a magic talisman.) Look, it’s been a ten-mile day. At 2:30 p.m., heat mounts out there, beyond these pools of shade beneath the cedars and oaks at upper Madulce Camp. Backpacking to the truck at Cox Flat will be much hotter than it was on the way in. Sunny glare, scratchy brambles to the side and overhead, poison oak, intense sunny glare, it’s rattlesnake time – intensely yang.

Utterly bemused and impressed by my own stupidity, I exclaim to Gabe, “Hey, we’re on a true adventure!” From his 6’ 2” height, bald as a Zen monk, with heavy black eyebrows, smirking hideously, Gabe indicates with a handwave that he agrees – and why mention it? He aims for the pools of silence. I concur, of course, and firmly clamp parched lips together.

That has been our pact: “Pools of shade, pools of silence.” Only the bare vibrations of strings being plucked on his three-pound Martin trail guitar, lots of Doc Watson stuff today. He’s reading Thomas Merton’s essay “Solitude is not separation,” and I’m reminded how much our silence is also no “separation.” We’re here together, son and father, sharing this predicament.

Scouring another desperate time in the area right by the campsite, we triple-check a most unpromising wooden box-like structure poking about four and one-half feet into the earth. It’s located on the southern edge of the fern patch, and actually there are two boxes. We found traces of water in the first one, nearby, which was only about a foot deep, but it had horrible black scum, ants, beetles, flies, and a dead rat or large mouse. Gross, and it smelled like rotten eggs (a sulfur-flavored gift from our Mother). We both nearly gagged. Impossible! But we need to get water out of Her.

The deeper box now merits intense study. It was obviously placed there, right over the spring, by the U.S. Forest Service (or by cowboys). Gabe, wearing his heavy boots, clambers down into the box, brushing cobwebs away: In the moist, matted dirt and muck at the bottom, he picks through a matrix of brush, leaves, centipedes, sticks, various insects — and there’s muddy sulfurous water there.

After a while, we can tell that more water is slowly seeping into a corner of the disgusting box, but it’s black and extremely gross. Using a broken-off cedar branch, Gabe starts pulling all the debris into the upper corner of the box, away from the corner where the seep is most obvious. This stirs up the junk and makes the black water even blacker, but it’s now pooling in the lower corner of the box.

Experience is worth something, even when plans change: I’ve brought along an empty, one-quart, plastic milk container, and now cut part of the top away. With it, Gabe manages to laboriously scoop out four liters of unbelievably stinky, scummy “water.” Hecate’s pinched breasts!

I haul it through the fern forest over to our campsite. Using our excellent “Sweetwater” filter (down to four microns, they brag; anti-giardia) we strain this disgusting brew into our water bottles. It’s now less dark, though still pretty gray. But the filter (water-purifier) keeps clogging, even though we constantly clean out the pre-filter. These delays make the process into a time-consuming nightmare. And the water looks and smells repulsive anyway.

We pour the worst water through my paper coffee filters, but they swiftly clog, too. That’s it for coffee for the next four days, mutters a silly part of my mind. I realize we can wash the filters off carefully (it’s weak paper) and reverse them. This helps. We’re so revolted by this warm, foul-smelling water that we decide to boil it hard, too. This we do, using a lot of our fuel.

Yeah, we boil the precious few liters really just to give us the courage to drink it. Which I’m doing now, and holding my nose as it pours into my mouth. Whew! It has an absolutely fecal odor. Gabe laughs, and the young Zen master drinks his with panache and a grin.

We’re already feeling better, having drunk about a liter each of our Gaia’s finest liquid masquerading as sulfurous swill. When I belch, a heavy sulfur odor wafts into my nostrils.

But Mother Earth has taken care of us, challenged us to fight through the yang hurdles of heat, fire danger, and fear of contaminated water, and to accept her yin blessings in disguise.

It’s August, and hot and dry yang appears to be in the ascendant, but it is not true. This vision-quest backpack, based on “pools” of shade and solitude and silence, turns entirely on two points: water, and our orientation to the eternal feminine. I believe it may only be back here, far from our machine civilization, that one can begin to seek out a spiritually authentic life.

The next day, low on water but without our backpacks, we chugged up the 3000 feet to surmount pristine, pine-covered Madulce Ridge formation (6500 ft). The sweet pine fragrance was heavenly as we sipped the putrid-smelling water in our water bottles. At this point, you have magnificent views into Alamar Canyon as well as all the way out to the Pacific Ocean. We continued hiking, and Gabe anxiously asked me if I was sure that the spring at Upper Bear Camp would be flowing.

“Of course, there will be plenty of pristine water at Upper Bear Camp spring,” I retorted.

“But you were so sure of yourself that there would be water at Madulce Camp, so why … ?” He started to ask.

But I quickly stated, “Because there’s always been water there. And we have to trust our Mother.”

When we hit glorious Upper Bear camp after crossing the Buckhorn Road – Gabe there first, hiking well ahead of his happy old Dad – joy and rapture at the sound, then sight, of pure, burbling, steadily flowing water.

True joy and happiness that our Mother had finally chosen to acknowledge our faith and our practical determination, Emerson’s self-reliance. What beautiful, tasty, clear liquid flowing between her ancient mossy banks! Contrast is everything, of course. This is holy water, and we genuflect before it with alacrity. I’m shoving my whole face right into a small limpid pool and joyfully sucking up water by the mouthful. Gabe, laughing delightedly, fills extra water bottles to bring back to our camp at Madulce. We don’t really speak: nothing to say.

Drinking straight from the source. The elixir of moist revelation pours straight down my throat, bypassing the brain. It’s as close to honest gnosis as I’ve ever come. No filtering, no boiling, no waiting, just instant gratification granted by our smiling Mother as I stick my face into her waters again and again, precious water dripping onto my dirty T-shirt. I’m sitting among thousands of happily mating ladybugs, and there are painful nettles about four inches from my left elbow. It feels appropriate: Gaia takes care of us at the moment, but painful nettles are just a few inches away. “Pleasure is the interval between two pains.”

We continue to quaff large amounts of what the Hindus’ would call amrith, heavenly nectar. Our frantic clambering and seeking after those liters from Our Mother’s body replace the goal of ascending up the Buckhorn Road to Big Pine Mountain.

On our third day we re-ascended the backside of Madulce Ridge, got over to the Buckhorn Road (it separates the Dick Smith from the San Rafael Wilderness), hiked 3.5 miles up the well-graded service road toward Windy Gap, then took the .7-mile hike up to glorious and pine-laden Big Pine Mountain.

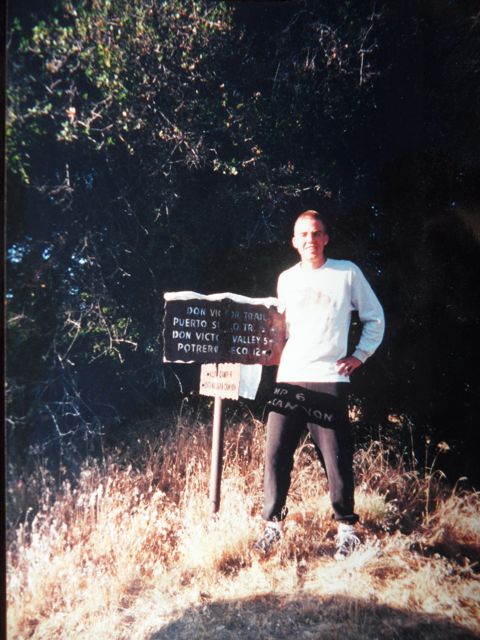

En route along the Buckhorn Road we also see this sign leading the hiker down the Don Victor Trail to the Puerto Suelo Trail, heading to Dutch Oven and Bill Faris Camps (not recommended).

On the way down to Madulce for the third night, we dropped into Upper Bear and re-filled all our water bottles. All told, Windy Gap, was an 8.2 mile day-hike sans backpacks, including the drop down to Upper Bear.

This was a near-disaster backpack, entirely the fault of the experienced father. We never made it to the Big Pine Mountain Camp, with its tiny spring, but we ascended the Santa Barbara County’s tallest peak, Big Pine Mountain itself.

In these latter days, the feminine is indeed in the ascendant. Look, we now have 20 female Senators in the 113th Congress.

What’s the final lesson? Love your mother.

Readers who wish to see more photographs of the lost Madulce Guard Station Cabin should check Eldon Walker’s images at Madulce Station Revisited.