Voices from the Community

Stories of Hope, Courage, and Change

Hateful Words by Ben Zimmer

When I came to Santa Barbara in 2009, I didn’t realize how much I hated myself for being gay. I had been in long-term relationships with men, identified as gay among friends, family, and coworkers, and was completely unaware of the homophobia I had been internalizing for years. In 2011, I began working for AHA! as a facilitator. One day in an activity on stereotypes, I decided to come out to a classroom of freshmen. Like clockwork, my palms began to sweat, my heart began to pound, and the room began to shrink. I felt as if I had returned to Shaker Heights, Ohio, where I was pushed down in gym class and laughed at outside of the choir room. Here I was, a 25-year-old gay male sharing my sexual identity with teens to bring awareness, yet the pain and fear still radiated from my gut. I took a look around. “That’s so gay,” and, “Don’t be a faggot!” buzzed as commonly as, “What’s up?” and, “Loser.” The hateful words and actions that instill self-doubt and low self-esteem among gay youth and LGBTQ individuals of all ages permeate through the hallways of Santa Barbara schools and down State Street.

I am proud to be a resident of Santa Barbara, where Pacific Pride stands tall and the “liberal” vibe is apparent to visitors. However, there is work to be done. While my best girlfriends are able to get married in New York City, I am scared to kiss a guy outside of The Wildcat on a Sunday night.

A Landmark Journey by Justin Valadez

The journey I have ventured to come out as a gay man was not easy. Assuming that there was something wrong with me because of my attraction to other men, I began to hate myself in high school. I desperately tried to keep my attraction hidden, and saw anyone who sought out the truth as a threat.

My parents divorced when I was eight years old. I lived with my mother in a city near Los Angeles and visited my father on the weekends. My strict father was never pleased with the way I was turning out. He would urge me to be manlier and constantly compared me to other, masculine boys. He even began to expose me to pornography at a young age. Finally, when I was 15, my father asked me if I was gay. I denied it, with sweaty palms.

We locked eyes and, very calmly, he said, “If you are gay, I will kill you…” He then began to explain how he would execute his plan. It was at this point that I created the context that I could not trust men: “I have to hide who I am or else they will kill me.”

After that weekend, I came back to my mother’s apartment and I overheard mom telling my sister, “If I ever find out that he is gay, I will kill myself.”

My world began to collapse. One parent wanted to kill me while the other one wanted to kill herself.

In my sophomore year of high school, accusations, rumors, and gossip about my sexuality were at an all-time high. It occurred to me that my life was spiraling out of control and no one cared.

I crafted a clever plan to protect myself from those who were out to hurt me. I began to mimic other male behaviors when I found myself surrounded by them. This double life and it became a part of my everyday routine. I would deepen my voice, broaden my shoulders, stick out my chest, and speak in a careless manner. My father’s approval of this version of Justin was enough for me at the time to justify the effectiveness of my tool.

For the next three years, I would present myself to others in one way and be completely the opposite with my closest friends. I was just getting by, with no commitment to ever changing this pattern until my cousin participated in a forum in Los Angeles that empowers and enables people to live the life they love by completing the past. He was a different man after The Landmark Forum, and my family including myself went to support him by attending the last session of his forum. It was there that I discovered a new world of possibility, and my mother also saw the opportunity and registered me into this three-day program.

It was there that I became aware of how inauthentic I was being in life. The impact this had on me was tremendous. What became available for me in distinguishing the inauthenticity was the freedom to be me. I was able to come out to my family as a gay man.

I moved out to Santa Barbara at the age of 18. At the time, I was not aware that there was a gay community in Santa Barbara and this caused me to temporarily revert back to defense mode. I attended the city college and was testing the waters for two years to see how safe it was for me to come out to people. One of the biggest struggles I had was not knowing who was involved with the LGBT community.

The relationship that I now have with my mom is better than I could ever have imagined, because I created the possibility of being open and honest with her. I acknowledged my father for the good times and forgave him for the bad ones. This created the space for him to apologize for his mistakes and, for the first time in my life, he allowed himself to be vulnerable with me, and our relationship has improved drastically.

I can now stand firmly in my own identity and share my struggles in the hopes that it helps others dealing with similar circumstances. I have committed myself to transforming the gay community by bringing love and acceptance to those who are not loved or accepted, utilizing film. Be self-expressed, love one another, and take action to cause a profound shift in the way we occur to the world.

Coming Out Is Hard to Do by Marylee Guerrero

Coming out? Probably the most difficult challenge I’ve had to overcome yet. My mom cried so much! She was sure it was just a trend I was following, making it a phase. She also suggested I should go to therapy to get fixed. But after some thought and rationalization, she said she was really just concerned for my safety because she’s seen how the gay community gets mistreated.

Fortunately, being out, for me, has not made my life any harder than if I was straight. I can fall in love, and I am just as susceptible to heartbreak as a straight person. People will judge, but that’s inevitable. You can be a heterosexual with a funky hairdo, and people will give you looks and jobs will turn you down. I can walk down the street holding my girlfriend’s hand, and people will also stare and make comments. It is my choice whether or not I will let the stares affect my day. I am open about my preference in both my jobs, and neither has treated me differently.

I am grateful for having it so easy, but I know not everyone does. I can’t generalize this, but from discussions I’ve had with friends, it is always agreed that homosexual males have a harder time in society. Only a male can answer that for himself.

Growing Up in the South by Robby Robbins

I knew when I was in junior high school, but I definitely was not out, and I wasn’t out all through high school. I dated the color guard captain. She was a lovely girl, and one of those girls who wanted to keep her virginity, so that worked out well for both of us.

In college, I was on the varsity men’s glee club and we were doing a tour of North Carolina, and were paired up as roommates. My roommate was Andy, and we were sharing a bed in a guest house, and things happened. I realized this is what I had been ignoring all my life. We dated for a while, until it became apparent that – well, let’s just say he had trouble being loyal.

I remember going to my first gay bar in North Carolina, a man’s man’s bar, lots of leather and wood. It was a butch bar. In the South, the bar culture was one of the few places you could meet other gay people. So I guess that’s when I came out to myself. (Everybody’s question is, “Have you ever even been with a woman?” The answer is yes, I have, I don’t hate it, and I’m pretty good at it.)

I started keeping a journal, a very personal, explicit, all-inclusive journal. I was home for the summer, and when I came home from work one day there sat my dad at the table, with my journal. I felt furious and invaded, and I just decided I was going to stand my ground. My dad shoved the journal over at me and said, “I hope that this is just some very sick fiction.” I said, “No, actually it’s some of my best writing ever.” I won’t bore you with the details, but the conversation didn’t go well. I ended up going nose-to-nose with my dad, who is 6’3”, and saying to him, “Go ahead and hit me. Hit your faggot son if it makes you feel better.”

Needless to say, things were weird. At home, and with my friends from high school. There were 26 of us who went to college together at North Carolina State, and all but one wouldn’t have anything to do with me.

After a period of time and exposure, and consistency and steadfastness on my part, my family have all come around. Those friends have all come back. I did go away for a year and not come home to see my family at all – and I’m a big mama’s boy. But I called once a week from a payphone just to let her know I was alive.

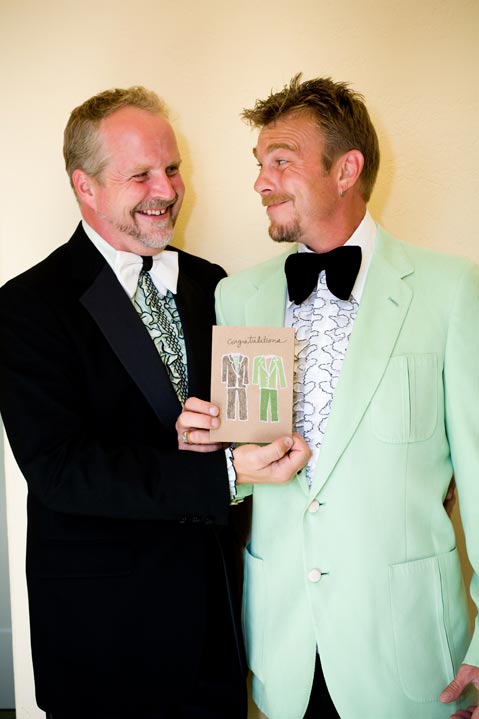

My father now loves my partner, Bryan, as if were a part of our family. He’s come a long way and I’m proud of him, because it’s hard for someone of his generation and upbringing. Even my grandparents came to accept my partner and be kind to him. All I ever asked was for them to treat my partner as they would any other friend of mine, with common courtesy.

In Santa Barbara, Bryan and I feel more comfortable touching each other in public, hugging longer than we would in the South, maybe a little peck – neither of us are big public-display-of-affection people. Nobody’s ever said anything to me. Yet we had those two guys beat up near Chapala and Ortega because they were holding hands. We’ve walked out of the Wildcat and crossed the street holding hands; that could’ve been us. That kind of thing gives you an unfortunate reality check.

Santa Ynez Roots by Felicia Rueff

I’m 33 now, and I don’t believe I really came out and came to terms until I was about 25. I was raised in a religious family, and I still have my faith, but I felt very morally conflicted. In the small town of Santa Ynez, where I grew up, being gay wasn’t something I was ready to recognize or act upon for fear of rejection at school – and knowing it wasn’t something that would be accepted in my home, because it was a sin, I didn’t even entertain the idea.

I felt very disconnected from my family for about two years. I spent so much time trying to keep things under control, worrying about whether my siblings were hearing about me. I had a younger sister in high school, and an older brother still involved in the community. Only my little brother was around, and he accepted and supported me.

As my family and I slowly started to build our relationship again, it was the elephant in the room. Nobody wanted to talk about it. I didn’t want to talk about it. Then, at 25, I became very depressed, tired of denying so many things in my life. And with no energy in me, I said, “This is who I am.” I was just so depleted. I didn’t need to have their approval at this point; I just needed to let it go.

Now, my family is so supportive, it’s just amazing. I’m open with them about my current partner, and I’m just so thankful that my family is letting me be free and love who I love.

Happily Shocked in Santa Barbara by Katarina Robledo

I’ve been out for about five years. I’m 26. I had a lot of anxiety about whether to tell or not to tell, but it actually went a lot better than I’d anticipated. I started in little groups of people and went from there, starting with my super-super-super-old friends, who said, “Kat, we already know.”

Then I branched out to less-close friends. I didn’t really plan it, but having grown up in Santa Barbara, I’d run into people and we’d say, “Let’s have coffee.” We’d be in deep conversation and I’d say, “Oh, I’m gay.” Most acted like it was no big deal, very nonchalant, as if I’d told them the sky was blue.

I started thinking, “Is that all I get? Where’s the drama?” Everybody talks about the moment of coming out, but I wasn’t really experiencing it. My family was pretty open about it. They weren’t, like, “Yay, she’s gay! That’s awesome!” But they were like, “Oh, OK. That’s nice. Well, it doesn’t really change anything about you or the way we feel about you.” I thought for sure somebody was going to have a problem, but everybody seemed to be on the same page. I was surprised by the reaction. Happily shocked.

I don’t feel prejudice in Santa Barbara, but a certain discomfort because there’s not a lot of diversity here, there’s a certain uniformity. The gay community is tiny, almost nonexistent, maybe because Santa Barbara is such a small city. Also, I don’t feel teens can express their sexuality openly. I didn’t know about the Gay-Straight Alliance at San Marcos High until senior year, and the only reason I learned about Pacific Pride was because the City of Peace counselors told me about it. I was thrilled. “Oh, cool, other gay people!”

Warm, but Could Be Cooler by Kevin Kearney

Santa Barbara’s gay culture, like the city’s culture in general, tends to focus on the past. When I first moved here seven years ago, most of what I heard about the city’s gay lifestyle were stories about how it used to be. At one time, so I have heard, there was not just one actual gay bar, but several! There were more gay people and more gay parties. While I’m not sure if the number of gay bars is necessarily indicative of a city’s cultural pulse or its tolerance (who needs gay bars post-Grindr?), everyone, straight and gay included, seems to talk about how much “cooler” and more diverse Santa Barbara was in decades past.

Many of the people that the city desperately needs to attract, such as young entrepreneurs, the middle class, and “hip” people (yes, gays are hip) are turned away by exorbitant prices and the city’s backwards-facing gaze. I live downtown, but I feel like the city is mostly controlled by the suburbanites who desperately want to preserve our “old town feel” and our “history.” And by history, I mean the simulacrum of Spanish heritage in the form of a tourist Disneyland. Lights out at 9, please.

That said, I wouldn’t trade my experience in Santa Barbara for anything. We may not be too cool, but we are warm, and I have only rarely experienced overt intolerance. I feel comfortable here. I have been fortunate to meet some of the best friends of my life. And while I think we can do more to attract people beyond the mega-rich, it is nice that Santa Barbara is not too sceney like West Hollywood, where all the gays do in fact look the same. Moreover, we have been blessed by the active and dedicated Pacific Pride Foundation, which supports a number of truly great events, not to mention a fantastic annual Pride celebration. But I think we can do more to increase the cultural, racial, and economic diversity of the city.

Last night my boyfriend and I watched a Solstice rock concert in the streets. Then we kissed under the full moon on the beach, right where I arrived in Santa Barbara seven years ago. We walked to the harbor and were splashed as the ocean smacked up against the barrier. So now I’m feeling nostalgic and thankful for all that Santa Barbara has given me.

Coming Clean to Myself by Jeremy Paarmann

For me being gay was such a dirty secret I even kept it hidden from myself. With the negative way peers referred to homosexuals, with disgust, I couldn’t afford to be anything like that. When friends believed the word gay was somehow synonymous with the word bad, and used it whenever they found something to be “stupid” or “lame,” it was hard to ever want to describe myself that way. I wasn’t stupid or lame, but somewhere hidden I knew I was gay, and before long it came out of me and I was terrified. Coming out to the rest of the world was something I tried to put off as long as possible because of the fear that I would be rejected or treated differently. I came out to my friends first. The ones that were uneasy with the idea of having a gay friend either came around or drifted away, but it was all good, because the ones that stayed at my side truly cared about me regardless of my sexual orientation. I didn’t want to crush my mother’s dream of having grandchildren from me or being at my wedding. But when I was finally able to open up to her, her dreams for me simply changed; she wanted grandchildren whether they were biological or adopted, she wanted to fight for and supported gay marriage. She was on my side, and so was everyone who cared for me. I don’t hide it from anyone anymore, now that I am out, I can’t imagining holding it back in. I learned to not be ashamed, but proud.

Anonymous

I’m a therapist, and I used to work with kids who assumed I was married and that my partner at home was a man, because I do wear a ring on my finger. Their automatic was to ask things like, “Do you cook for your husband? Do you have any children? What’s his name? What does he do?” I felt myself always deflecting it. Some of their parents, I knew, were definitely very anti-gay, very homophobic because a couple of the kids were identifying as bisexual, and I knew the parents’ opinion on that topic. I had to take into consideration that if they knew, they probably would not want me interacting with their child.

It was close to when I knew I wasn’t going to work there anymore, and the kids had some leading questions, and my intuition was that they were asking me these questions because they knew somehow that things weren’t adding up. After four years of their confiding in me, and taking risks, I felt that was something I wanted to give back. So that’s how I framed it, that they had opened up and taken risks, and I wanted to be open and honest and honor the questions they were asking.

And in the last couple of months I had with the kids, I think we got closer than we had been before, in a shorter amount of time. They were sharing more things because I had taken a risk and put something very personal on the table.

There was no blowback from the parents. I know that at least one student did tell her parents because she told me she had asked her mom, while her mom was cooking posole, that she wanted to invite me and my girlfriend, is how she put it. Apparently, her mom had no problem with it, and we did get invited, though we didn’t go because we were out of town.

I just got a new job. I’m just not sure how [the directors] would feel about my being gay.

The B Is Not Silent by Justine Sutton

In the oft-used term LGBT, the B is generally silent, unfortunately. In other words, the problem with being bisexual is that we are often invisible, because both homosexual and heterosexual people tend to believe we don’t exist.

In college I recognized that I was bisexual, and in my early 20s I met an older woman, an artist and established lesbian, who was not shy about expressing her interest in me. I liked and admired her, and was flattered and curious. We dated for a short time, and in the throes of this infatuation, believing myself to be a lesbian, I came out to my mom on the phone. I will always remember her words: “It’s not the path I would have chosen for you, but I just want you to be happy.”

Quickly it became apparent that the relationship was not working for me. I assumed the problem was that I really wasn’t into women after all. It was very difficult to break it off with her, as she didn’t accept my decision. When she would show up late at night at my door with flowers and moony eyes, it didn’t help that, more than once, I decided to give it “just one more chance.” I cringe at the memory, but it wasn’t malicious, only naive. Just the same, I was vilified by her circle of close lesbian friends as the “straight girl who broke her heart.”

A few years ago, I met a woman with whom I had instant chemistry. I was well on my way to falling for her when she broke my heart by informing me she didn’t want an emotional relationship but would be interested if I just wanted to keep it physical. Damn, I thought only men did that sort of thing.

Now in my mid-40s, I have had long-term relationships with two men and briefly dated these two women. I am open to dating either gender. I identify as bisexual.

The attitude of mistrust among gays and lesbians in Santa Barbara and elsewhere is particularly disturbing to me. I have often heard from them that bisexuals should just “pick a side.” Meanwhile, I think straight society feels uncomfortable with bisexuality because it brings to mind the idea of promiscuity. It seems to translate in people’s minds to “sleeping with everyone, all the time.” In fact, just as there are plenty of heterosexuals who are not committed to monogamy, there are bisexuals who commit to be with only their partner, man or woman.

Dressing Proud by Michelle Carter Linares

Being in high school was a scary thing for me at first. I was the one who always looked different, all the girls dressed one way, all the boys in another and then, there was me. I wanted to change a lot about myself, but the fear of losing myself in the process is what stopped me from being a follower. After I dated a girl for about a year or so, I became the tomboy with the saggy jeans, tee shirt, Converses, and snapback.

I didn’t like the feeling of having people stare at me all the time just because I dressed like a boy, so I decided to be a girly girl. You know, the whole makeup, skinny jeans, boots, cute-laced-shirt type girly girl. Over time, I couldn’t shake off this feeling of guilt. Being a girly girl just wasn’t me. Although I enjoyed the attention I got from boys, I decided to leave my girly days behind and found myself back in saggy clothes again. It seemed like “me,” and as long as I was happy, that’s all that really mattered. Everyone talks, might as well give them something to talk about.