Affirmative Reaction

A UCSB Diversity Analysis Post-Supreme Court Ruling

Obscured in the shadow of two bombshell civil-rights decisions by the Supreme Court last week was a third ruling on affirmative action in higher education that has reopened discussions on the wisdom of admissions policies that consider race. The court did not overturn the precedent it set when it ruled in 2003 that colleges and universities may implement such policies if they deem diversity among the student body is an asset to the campus, but it did send the case back to a lower court insisting that the defendant — the University of Texas — prove an affirmative action plan is necessary to reach that goal.

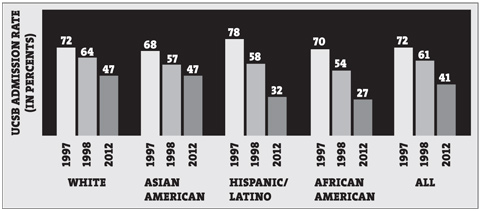

Closer to home, in California, affirmative action has been verboten since 1996 when voters passed Proposition 209, a crippling blow to diversity at the state’s two highest-profile public universities, UCLA and UC Berkeley, from which they have not yet recovered, an analysis by the Los Angeles Times revealed. A similar look at numbers made available by the University of California Office of the President shows that minority acceptances at UCSB have not recovered to pre–Prop. 209 rates. This data is tempered by the fact, however, that as applications to UCSB have skyrocketed, the total acceptance rate between 1998 — the first year after Prop. 209 first took its toll — and 2012 dropped by 20 percent, and the acceptance rate for whites dropped 17 percent. During that same span, the acceptance rate for African Americans dropped from 54 percent to 27 percent. The Hispanic/Latino rate dipped from 58 percent to 32 percent. (The year before Prop. 209 took effect, 77 percent of Latinos were admitted.) On the other hand, the campus has continued to diversify as almost a quarter — 22 percent — of currently enrolled students are Latino.

Associate Dean of Student Life and Activities Katya Armistead clearly remembers the day Prop. 209 passed. “Quite honestly, it was a sad day for me,” said Armistead, who was working in the admissions office as a campus visit coordinator at the time. “It was a tool for outreach to look for the best students, period.”

“We are a bit more geographically isolated than some of the other campuses, which can be a challenge to recruiting students, especially those from lower-income families who must travel farther distances to visit,” said Lisa Przekop

Aside from acceptance rates, UCSB has historically had a hard time attracting minority students because of its location, which is not part of a major metropolitan area. The population of black students has held steady at 3 percent since 1997. “We are a bit more geographically isolated than some of the other campuses, which can be a challenge to recruiting students, especially those from lower-income families who must travel farther distances to visit,” said Lisa Przekop, associate director of admissions.

“Once we get them exposed to UCSB, we do pretty well,” said Armistead. Retention efforts are centered around the Equal Opportunity Program, which automatically enrolls first-generation college students and those from low-income families. However, any student may join the program, which houses resource centers for Gauchos of various ethnicities. The MultiCultural Center also provides programming and a sense of community for minority students. The university — along with minority student groups — puts a great deal of effort into outreach programs.

As for recruitment, Przekop said, “We visit over 500 high schools in California alone each year, as well as more than half of the community colleges. We target inner-city as well as college preparatory schools. We also spend considerable effort in developing a strong network of college counselors in the high schools and community colleges that we visit.” She added that the office employs Spanish-speaking staff to communicate with families and that Admissions will soon add a position specifically for recruiting underrepresented populations.

That upcoming hire is a result of a list of demands the Black Student Union (BSU) submitted to Chancellor Henry Yang earlier this year, including the addition of two counseling psychologists who specialize in working with black students and a plan to recruit black faculty outside of the Black Studies department. They found that the head of the university was — somewhat surprisingly — extremely receptive to their concerns.

A longtime advisor to the BSU, Armistead attended UCSB as an undergraduate affirmative-action admit and has gone on to earn a doctorate in Education. Specifying that she was not speaking as a representative of the university but as an individual “who works closely with students and cares about diversity,” she said, “People have the wrong idea of what [affirmative action] means. It’s not about admitting people that have achieved less than others. It’s about opportunity.”