On the Safety of Firefighters

Real Time Danger During the Jesusita Blaze and Human Lives vs. Expensive Homes

At the 6 a.m. briefing on Wednesday, May 6, engine crews, hotshot teams, dozers, water tenders, and other firefighting resources assembled at Earl Warren Showgrounds for the day’s assignments in attacking the Jesusita Fire, which began the afternoon before.

The strategy was perimeter control, including direct attack by the hotshots, use of water-dropping helicopters on the San Roque side of the fire to cool things down while crews cut containment line, and the addition of both large and small fixed-wing aircraft to begin laying down retardant on the east and south end of the fire. The goal was to slow down the advance of the fire perimeter, which was expected to pick up later in the day.

An Air of Confidence

Despite the strong push the fire made Tuesday afternoon to the top of Inspiration Point, as the evening winds died down so did the fire. By Wednesday morning, it seemed like firefighters would be able to get things under control. “I think we were all pretty confident that morning,” remembered Santa Barbara City Fire Chief Pat McElroy.

In a Cal Fire report titled “Jesusita Fire Burnover,” which reviewed injuries, accidents, and near-misses, the fire was described as “punking around” that morning, thus providing the critical time to prepare for what might come later.

Meanwhile, fire resources were beginning to pour into the Santa Barbara area, and given our recent fire history — the Tea Fire consumed more than 200 homes just six months earlier — no one worried about how many engine crews to order, how many air attacks to request, or what it would cost to bring them here. When Santa Barbara fires break out along the urban-wildland interface, billions of dollars of property are put at risk.

NOAA weather reports indicated warmer temperatures and winds later in the day, and sundowner conditions were a possibility, but likely not until dusk. Despite the promise of good firefighting conditions during the day, those on the fire line knew all that could change at any time.

Orders and Watchouts

In 1957, after several decades of tragic fires in which numerous firefighters were killed, the Forest Service commissioned a task force to review 16 fires between 1937-1956, assess causes for the loss of lives, and establish safety guidelines to help prevent future casualties.

Out of the task force effort came what are known as the 10 Standing Firefighting Orders and 18 Watchout Situations. Among these is Order #2, which is to know what the fire is doing at all times, and Order #3, to base all actions on current and expected behavior of the fire.

Three specific scenarios play in the firefighters’ minds as the assignments are handed out at Earl Warren Showgrounds. One of these reflects what might be called typical fire behavior, by which the fire front moves uphill following the steep topography to the crest of the Santa Ynez Mountains, with the radiant heat and flames preheating the brush up above, creating firestorm conditions. It is also possible the fire could continue in an eastward direction across Mission Canyon and follow the base of the mountains into the Montecito area.

But what worries the Incident Command Team the most is the potential for sundowner conditions, strong downhill winds and the searing heat that comes with them. That would mean a direct hit on the homes immediately below Inspiration Point. Squeezed between there and Foothill Road are more than 2,000 houses from Northridge Road east to the far side of Mission Canyon, many of them packed like sardines in the Mission Canyon Heights area.

Structure Triage

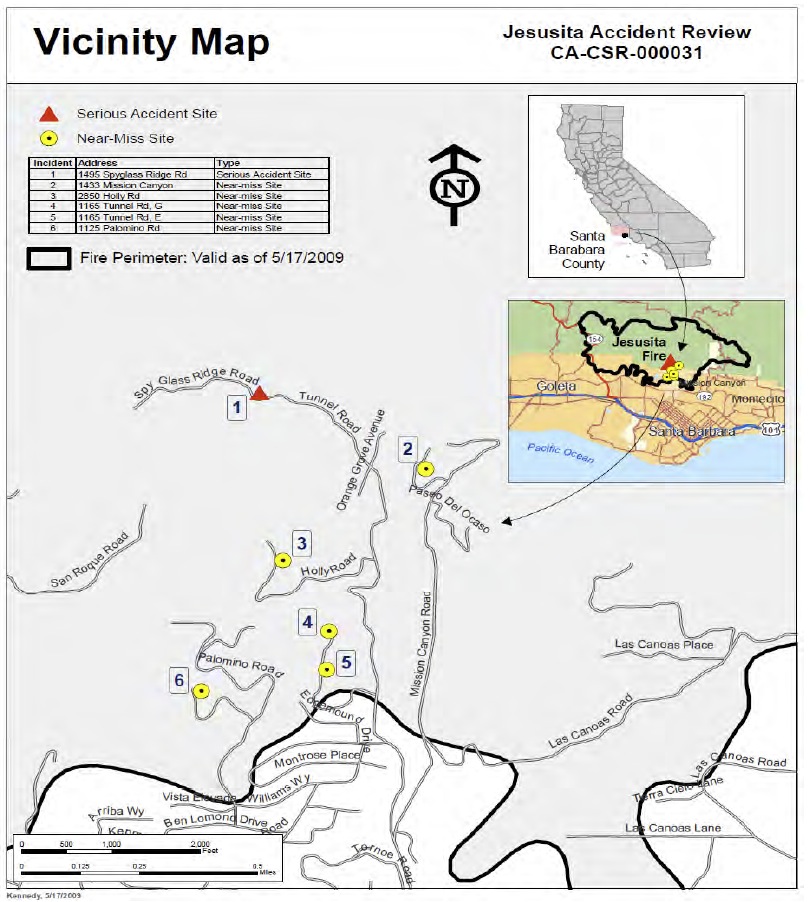

While hotshot crews were busy making their way toward the upper east and west flanks of the fire to begin building containment lines, and air resources were working to slow down the movement of the blaze, scores of Type 1 and Type 3 strike teams had been assigned to protect the areas considered to be the most threatened, including Spyglass Ridge, Holly Road, and Mission and Tunnel roads. Typically a Type 1 strike team consists of five engines, each with a crew of three to four firefighters and a battalion chief. At that point, 50-60 engine crews were moving into the neighborhoods with more on the way.

By 9 a.m., most of the strike teams were on the ridge conducting safety briefings, assessing locations for safety zones — an area large enough to which they could retreat should the fire approach their positions — and marking evacuation routes.

With relatively mild fire behavior above them, the engine crews were able to spend the morning performing what is known as “structure triage,” including moving combustible items away from the homes and outbuildings; cutting out vegetation near the homes; cleaning out rain gutters; and applying aluminum foil to vent openings. At the same time they began positioning their engines in defensive positions and started laying down hose lines that would allow them to spray water on advancing flames from multiple spots around the structures.

Fighting a wildfire in the midst of such conditions is difficult at best and exposes the firefighters to potentially lethal conditions should the fire front head their way. The streets are narrow, winding, and overgrown with brush, with little room for the engine crews to pass one another should they need to. The private driveways in areas like Spyglass Ridge, Owl Ridge, Holly Road, and Palomino Road are even steeper and narrower.

Making things even more difficult was the fact that almost all of the engine crews were from out of town, didn’t know the territory, and didn’t know how a fire behaves on the Santa Barbara front when a sundowner is in play. In a nutshell, we were asking firefighters from out of the area to risk their lives for people they don’t know, in an area most of them have never been before and most likely may not ever be again.

“Every year all of the firefighters go through what is called ‘Critical 24’ training to prepare us for wildland interface fires,” said Mike Mingee, fire chief for the Carpinteria-Summerland Fire Protection District. “The Standing Orders and Shoutouts, along with the training, should allow us to be prepared for fighting a fire safely wherever we go.”

Unfortunately, when conditions change as rapidly as they did the afternoon of May 6, the firefighters discover they are not prepared for what comes next.

Jesusita Fire Blows Up

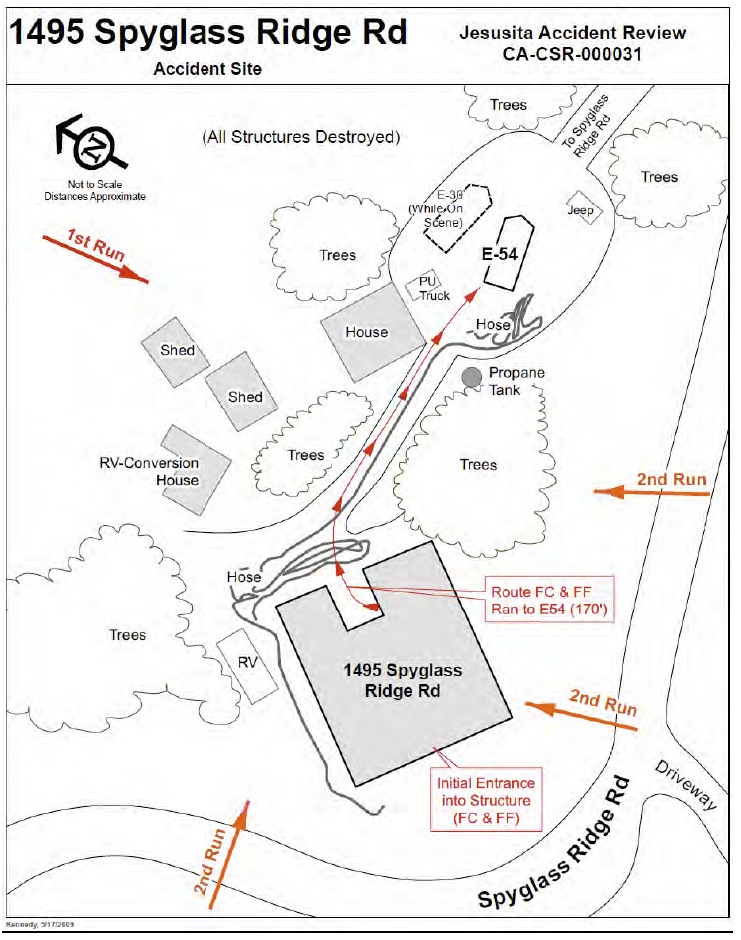

At one of the houses considered particularly vulnerable, 1495 Spyglass Ridge Road, Ventura County Engine Crew E-54 began pre-positioning resources should they be needed, including hose lines around the main house and driveway and three self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) inside the living room of the main house. By noon, much of the preparation had been completed and the crews were completing final checks.

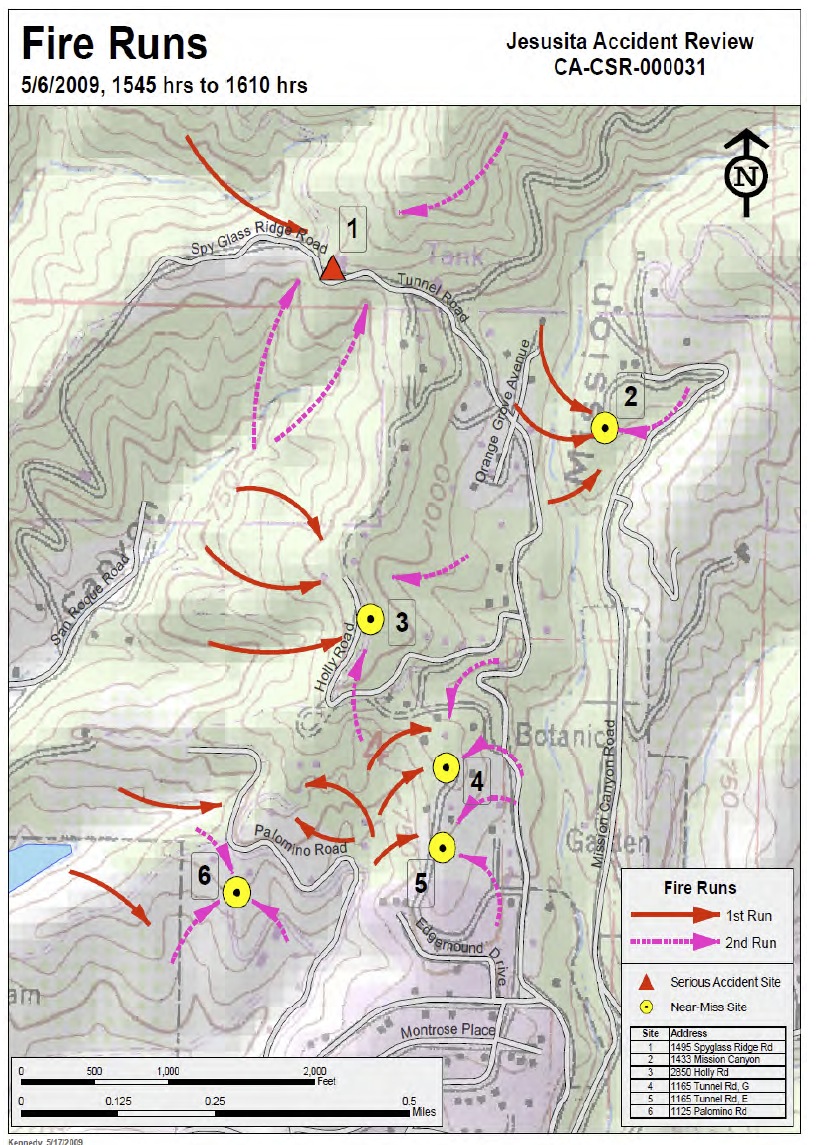

Then, almost like a switch had been turned on, the winds began to blow, directly downhill and directly at the engine crews throughout the Mission Canyon area. Just after 2 p.m., fire activity began to increase on the ridge above their position and to move down the slope toward Spyglass Ridge Road.

By 3 p.m., spot fires were starting to take hold throughout the canyon as 30-40 mph winds pushed red-hot embers high into the air and out in front of the advancing flames. By 3:30 p.m., several spot fires were reported near 1495 Spyglass Ridge, causing the E-54 crew to request backup support. An additional engine crew, E-30, quickly responded, backing into position next to E-54, their goal to use their water supply to slow down the fire, which was now almost directly upon them.

Within minutes, realizing these efforts were futile against what was described as a 100-foot wall of flames, the E-30 crew dropped their hose lines, donned their SCBAs, and took refuge in the cab. At this point E-30 ran out of water. Frantically, the crew attempted to drive down the driveway to safety but were halted by a wall of flames. Then, when there was a break in the flaming front, they scrambled down the driveway dragging all their hose and nozzles.

Firefighters in Danger

With the majority of the main house burning, the E-54 crew members were left to fend for themselves. The fire captain, Ron Topolinski, and one of his crew members, Robert Lopez, retreated into the main house for protection. Lopez crouched down and prepared to use a fire shelter as a heat shield while exiting the structure. But before the fire shelter could be fully opened, the sliding glass door shattered and a rush of heat entered the room, forcing both men to scramble outside and toward their engine.

Lopez later described the situation to Ventura County Star reporter Kathleen Wilson. “I felt my shoulders on fire and my arms on fire,” he said, adding that he rolled on the ground to try to stop the fire from burning his skin.

While Lopez was on the ground, Topolinski continued up the driveway toward engine E-54. He yelled back at Lopez to continue to the fire engine, then climbed into the back seat on the passenger side with the help of Captain Brian Bulger. At that point Topolinski was still wearing his SCBA, with barely enough air left and the low-air warning device sounding. Thankfully, Lopez arrived not too long after, jumped into the cab, and Bulger was able to move them to a safer location on Spyglass Ridge where a paramedic crew treated Topolinski and Lopez.

Conditions in other parts of Mission Canyon were as poor as they were on Spyglass. Near the Botanic Garden another crew was facing a similar situation with 100-foot flames advancing in their direction. They were a bit more fortunate in that they were able to retreat to a small open area. Though far short of the recommended 400-foot separation for flames of that length, they were able to survive with minor heat exhaustion and smoke inhalation injuries.

On Holly Road, along the ridge to the south of the homes on Spyglass Ridge, conditions were almost as severe. Multiple spot fires were sparking downhill and then blowing uphill toward Holly Road from both the east and west sides of the ridge, resulting in extreme fire behavior within a short period of time. Compounding this, the fire hydrant system in the area lost pressure and then failed.

Immediately, the strike team leader there ordered the crews and a number of residents who had not evacuated to seek refuge. Five of the firefighters and five civilians took refuge in the residence at 2910 Holly Road, with several other firefighters retreating into the home at 2911 Holly Road after their escape route down the road was blocked by flames, and several more sought shelter at 2931 Holly Road. Those at 2931 Holly were eventually forced to flee from there to 2921 Holly when it became evident that the house would not survive the fire.

Complicating the immediate danger created by the advancing flames was having to deal with residents who were trying to evacuate. One of the firefighters related a story in which one of the residents, after being told to take refuge with him, announced he was going to leave.

“No you’re not,” the fireman told the resident. “Yes I am. Get out of the way,” the resident replied.

“You cannot leave,” the fireman said. “You’ve had two days to evacuate. You’re staying.” And the resident said, “No, we can make it. We’re leaving now.” The firefighter said, “No, you’re not.” Then the man said, “Get out of the way,” and told his wife to drive, which she did.

As he watched the couple drive away, not knowing if they would make it or not, the fireman took a few minutes to reflect on the confrontation. “That was a sick feeling,” he said. “We started to realize, uh, you know, what? We might not make it out of here. I mean … we’re in a bad spot.”

Firefighters Recover

On a morning in July, several months after the Jesusita Fire was over, Lopez, Topolinski, and Bulger were honored for their dedication and their bravery by the Santa Barbara and Ventura County Boards of Supervisors. By then, Bulger, who is reported to have lost 20 percent of his lung capacity, and Topolinski are back at work, a bit overwhelmed by the honors. Lopez, the most seriously injured of the three with second- and third-degree burns, plans on returning as well, if he can. As reported by Kathleen Wilson, the experience was 25 minutes of pure hell for Topolinski, one in which “we didn’t know whether we would get out alive or not.”

“We had a 10-minute period where we totally lost communication with these guys,” Santa Barbara City Fire Chief Pat McElroy remembered. “We feared the worst given what we’d been hearing on the radios before that. Those were 10 of the longest minutes of my life.”

A Shift in Attitude

Over the past several years, there has been a noticeable shift in attitude regarding the dangers in which we place wildland firefighters. In 2008, the Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics (fseee.org) initiated a lawsuit designed to push for wildland firefighting reform. “Firefighters should not be asked to defend a home that is indefensible,” said former FSEEE field director Bob Dale. “No home is worth a firefighter’s life.”

As is the case in Santa Barbara, the primary concern is not the backcountry wildland fires like the 240,000-acre Zaca Fire in 2007 that burns for two months but consumes no houses. It is the homes that have been built in the past 20-30 years along the base of the Santa Ynez Mountains that worry firefighters. This is the point at which the wildland meets an encroaching urban community. What is different here is that you are asking Forest Service employees trained to fight wildland fires to respond to the urban interface and you are asking city firefighters trained in defending structures to do so in a wildland environment.

“In a house fire the dynamics are the same every time,” Chief Mingee explained. “I know exactly how it will progress and what the fire behavior will be like. But on the wildland interface, conditions can, and often are, totally unpredictable.”

What is also different is that the impact of the vegetation surrounding the house and the susceptibility of the house to ignition are factors that firefighters had little control over until recently. The primary issue to firefighters is whether there is enough space around the homes and enough fire resistance to the homes themselves to allow the crews to defend them safely.

What FSEEE and others now argue for is a paradigm shift whereby it is the homeowner and community’s responsibility to make conditions safe for them to fight fires, rather than the firefighters’ responsibility to defend homes no matter what the conditions.

While the near misses are often forgotten quickly by the public, the firefighters do not. “We tend to lose focus on the near misses like on the Jesusita when we are faced with losses like the five Forest Service firefighters killed on the Esperanza Fire or the tragedy with the Granite Mountain Hotshots,” said Chief McElroy. But those near misses are just as critical. Sometimes it is just fate that stops them from being fatalities. Some mistakes were made that put those folks in a terrible situation, and we need to question how that happens. We owe it to them, and we need to evaluate whether what we are asking them to protect is worth the risks they will take, because they will take those risks.”

Red Dot, Green Dot

In his book, The Esperanza Fire, John Maclean describes a defensible structure strategy one might call “red dot, green dot” — whereby firefighters have informally labeled which houses they’ll be willing to defend and which one’s they won’t.

“Here we call them winners and losers,” said Mingee. “It’s probably not politically correct to use terms like that anymore,” he said with a laugh, “but the point is we are always preplanning so we know ahead of time what we can defend and what we can’t.”

“The Granite Mountain incident made me take a hard look at some of the issues involved in defending structures where nobody was at home,” Mingee added. “I’m not an expert in the kind of fire they were defending against, but I am a guy that has a responsibility for the lives of a certain number of people. The vegetation will ultimately grow back, the houses can be rebuilt, but the lives of my firefighters and their families can’t.”

Mingee sits and thinks for a bit. “We have a basic philosophy,” he said. “We’ll risk a lot to save a lot. I don’t think there is a firefighter out there, man or woman, who wouldn’t go into a building with the proper gear to rescue a person who’s trapped inside. That’s what we do and that’s what we’re called to do. That’s risking a lot to save a life.”

Roughly speaking, that means his firefighters will put everything on the line to protect lives, but many are now thinking that the same shouldn’t apply to risking lives to save things that can be replaced.

Then Mingee continued, “During the Tea Fire I looked in the face of Kevin Wallace, then fire chief for the Montecito Fire Protection District,” Mingee remembered. “He told me, ‘This is my worst nightmare,’ and I saw it on his face. I don’t want to ever go through that, but I’d much rather go through that than knock on the door of someone’s wife and say ‘I’m sorry to tell you what happened today.’ No fire chief wants to have to do that. That versus a home being lost, vegetation being lost, I’ll go for the lost home every time over risking one of my firefighter’s lives.”

Like Mingee, many other chiefs are facing similar situations. Given his druthers he’d come down on the side of his firefighters every time. But that is not realistic. “When there’s a fire,” he said, “we are continually doing triage — balancing the resources out there we are committed to protecting against the conditions relating to the structures you want to protect.”

“The first thing we look for is defensible space,” he continued. “Is this a place we can go and ID a safety zone as well as an escape route if things turn bad. If we don’t have that we’ll turn to a strategy we call ‘fire following’ whereby we’ll wait until the front has passed through and then go in and do what we can to protect the structures.

“Given the economics today, there is no fire department that can jump on every single thing that can happen,” Mingee added. “The Santa Barbara area has a potential disaster waiting to happen hear every few years. There’s no way my fire department or any of the others can protect every home when we have a fire in sundowner conditions, so it’s time people have to start taking care of things themselves.”

A Final Message

So I asked Mingee, “When you go out and visit those homeowners, are you being that blunt? When you know in your mind that someone’s house is a loser, are you able to be upfront enough to say to them, ‘Hey, if you don’t make these changes we won’t be able to protect your home?’”

The chief pauses for a bit, then he responded this way: “Should I tell them that if they don’t do their jobs [meaning defensible space and home-hardening retrofitting] we can’t do ours?” He said. “No … but it might be time to reconsider that. I don’t want to be the Fire Chief or parent that loses a 21-year-old old son because the homeowner didn’t do their job.”

So what’s the message that Chief Mingee wants every homeowner who lives in high fire severity areas to hear loud and clear? “Prepare now while you have plenty of time,” he said, “because when, not if, the wildfire comes, your local fire department and firefighters will do their very best and bravely provide those vital services you pay for with your hard-earned tax money. But we are going to avoid sending any more men and women to their deaths.”