My Life: Paddling Through the Storm

A Year in My Life of Living Dangerously

The last time I wrote a word for this paper – or any publication for that matter – it was early July, and, unbeknownst to me, I was bleeding internally at a rather rapid rate thanks to a baseball-sized cancerous tumor growing deep in my gut.

More specifically, it was a Tuesday evening, and I had an approaching deadline when, while working on a lead news story about the latest evolution of the Naples development saga, my cell phone rang. On the line was my primary doctor, and when your doctor calls you after hours, it is usually not a good sign. Roughly 12 hours later — and after filing my story for The Independent — I was admitted to Cottage Hospital. Nothing has been the same since, and I am fairly certain it never again will be.

This story, however, truly begins exactly one year ago when, after pushing my way through what I thought was a particularly brutal bout of the flu, I also ended up in Cottage. I started feeling lousy on the weekend after Thanksgiving, and, following a couple weeks of on-again, off-again fevers and assorted other symptoms that just wouldn’t quit, I finally dragged myself to urgent care. Flash forward five days that included a return visit to urgent care and two trips to the emergency room, and I was admitted to Cottage with what they were calling a “fever of unknown origin.”

In short, my body was shutting down, and basic functions, like peeing, for example, had long since stopped. I was numb from the middle of my chest down, my motor functions were anything but normal, I hurt in a way that all the Aleve in the world couldn’t touch, and I was more scared than I cared to admit.

I remember the moment when the ER doctor decided to admit me. He had a grave look of concern on his face despite his obvious efforts to appear otherwise, his eyes avoiding mine and falling instead on my wife, Anna, who was sitting next to me. “I think things just aren’t cutting it at home anymore,” he said. Moments later, a glass door slid shut on my room. Subsequently, all of the nurses and doctors started wearing masks and gloves when dealing with me. By the next afternoon, I would recognize the rotating cast of medical professionals by their shoes.

In the 12 months since that terrifyingly surreal day, I have been diagnosed with all manner of ailments, including shingles, a bleeding ulcer, transverse myelitis, meningitis, multiple sclerosis, and, ultimately, a very rare form of pancreatic cancer that has gained a certain amount of infamy worldwide as it is the same disease that killed Apple founder Steve Jobs.

While most of the diagnoses stuck, some have been abandoned, and others remain in the “only time will tell” category. I have had no fewer than 125 doctor’s appointments, being seen by specialists at Sansum Clinic, at USC in Los Angeles, and Stanford Hospital in Palo Alto. Each visit delivered plot twists of varying degrees and proved repeatedly that, while the knowledge doctors hold is massive and ever important, it is also minuscule and often powerless compared to what they don’t know or don’t understand about the human body.

I have spent just shy of 30 nights in a hospital bed — Anna by my side for every one of them — and today, as I sit typing this very sentence at my dining room table, I am officially back to work, albeit with a big scar on my belly, some new interior anatomy, and my head spinning as I try to make some sort of sense of this life-altering journey that has taken me from one holiday season to the next. It has been a long and trying year, and, like all of us still fortunate enough to be among the living, I have had no choice but to go through it.

However, despite a holy host of reasons to bury 2013 in a pissed-off pile of ill will, I am feeling quite the contrary these days. Certainly my future is unknown; as anyone who is in the cancer-survivor club will tell you, this disease is a cruel and wicked and deceptive and remarkably unfair opponent that can strike back at anytime with nary a warning shot. This is a less-than-ideal reality that colors every moment I live from here on out, but it is my reality, and, as bizarre as it may seem, I am thankful for it. You see, something funny happened during all the blood tests and MRIs and maddening medications that makes me feel like a stranger in my own body. Somewhere during the fear and hardships and anger and haunting unknowns that have dotted my days since last December, I began to slow down and soften and surrender. And in the process, I have rediscovered the unrivaled magic that is life itself. It turns out simply being alive is some seriously intoxicating shit.

Trouble Ahead, Trouble Behind

After my first stint in Cottage, I was cut loose to the freedoms of the outside world just before Christmas Eve. Believe me when I say, a hospital is a damn fine place to have your life saved, but it is no place to actually heal. It was a crisp and cool Monday evening as I made my way across Bath Street toward my wife’s car. My step was shaky but resolved, the smell of a recent rain flared my nostrils, the orange hues of a blooming bird-of-paradise more vivid and complete than anything I had seen in days.

At that time, my primary diagnosis was something called transverse myelitis, a fairly uncommon and mysterious neurological affliction hallmarked by lesions inside your spinal column, and one that is diagnosed no more than a thousand times a year in all of America. I was on lots of medications, but I felt good and was confident that the worst was behind me. I rolled the window down and hung my face out into the wind on the way home like a dog. By Christmas morning, after attempts at weaning myself from my meds spiked my previously abating symptoms, I knew I was not fated for such a quick fix.

The next few months were, in hindsight, an incredibly peaceful time as I made my way out onto the tundra of medical mystery. I began seeing a Chinese medicine practitioner and acupuncturist, a decision that has been among the most physically and emotionally beneficial that I have ever made. I gave up alcohol and caffeine and gluten and dairy and sugar and meat and nightshade vegetables (a diet my friends like to call the “no fun” diet). I began meditating and daily visualization exercises. My more traditional doctors started me on intravenous blood therapies and off-label uses of other medications. Progress was slow, but with time, I was back at work and steadily reducing my drug dosages. I think back on these winter months, and my mind’s eye sees a low light shining through my living room window, a hot cup of tea steeping next to me, and my dog, Danger, asleep on the rug. Before I knew it, spring was in the air, but answers, despite the improvements in how I felt, remained elusive.

By mid-April, I was able to go on short hikes and even surf a little bit again, two things that have long been paramount to the health of my spirit. I was buoyed by these developments but felt in my core that all was not well. I had hit a wall it seemed, one where I could continue to step down my medications without getting much worse but also without getting much better. My stomach bothered me most mornings, and fatigue gnawed away at me no matter how much I rested. I figured this to be par for the course considering my situation, and, falling back on old patterns of behavior and ego-driven resilience that had served me well over the years, I pushed on despite the growing voice inside of me telling me that things just weren’t right. The power of the mind to both heal and hurt depending on what you choose is truly amazing.

And so it went until late June, when, during a sweeping battery of tests ordered on the six-month anniversary of my initial hospital stay, it was determined that I had become anemic. Unfortunately the doctors hadn’t been looking for anemia, so they weren’t sure exactly what

type I had; another round of lab work was ordered. With Fourth of July festivities unfolding and work duties calling, I dragged my feet on getting the blood study, waiting until after the holiday weekend.

During my lunch break on that aforementioned and fateful Tuesday, I went in for the tests, and before the day was done, my primary called with the news — I was even more anemic than I had been just 10 days prior. In fact, I had become dangerously anemic, and an immediate trip to the ER was recommended. I will never forget sitting alone in my office in a queer disconnected state staring out at my coworkers as his voice rang in my ear. “There are really only two explanations for something like this, and neither is very good,” he said. “You are either internally bleeding or something like an advanced cancer is going on.” Turns out I had both.

Surging Seas and Turning Tides

An abnormal mass — which had iceberged into my small intestine, causing internal bleeding and thus the anemia — was discovered the next day. By the following Tuesday, it was confirmed cancerous — a neuroendocrine tumor on the head of my pancreas.

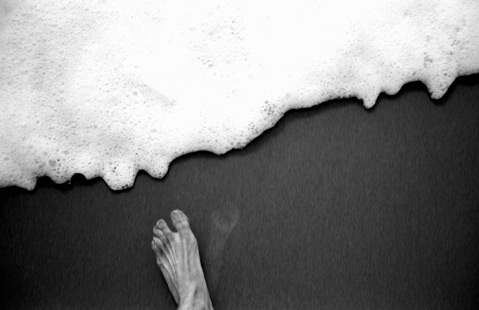

The bad-news call came as I was driving in Goleta to walk my dog at Ellwood, my wife and mother in the truck with me. I continued on toward the beach in a freefalling daze, stripping down to my shorts once I hit the sand. I walked slowly to the ocean’s edge, leaving Anna and Mom behind me. The heaviness of the news was too much for me to bear, and the tears flowed as I hot-stepped into the Pacific.

I dove under the first wave that came to me and screamed a word that isn’t fit for print deep into the depths. I stayed under for a long time, and, when I resurfaced, my tears and the Pacific were one. I noticed the water dripping off the tips of my fingers, the blue of the sky caught fleetingly in the little drops of water before they returned to the deeper greens and blues of the sea. Turning shoreward, my eyes locked on Anna and my mom, the two most important people in my life, and, despite the fear pulsing through my body, I felt an upwelling of something much bigger inside of me, something akin to gratitude but more complete and sweeping than I have ever known. It didn’t last long that first time, but it was definite and distinct and powerful and it gave me the courage to go back to the beach and all that awaited me.

The next 10 days were the most intense and humbling I have ever lived. During this time, I circled the wagons with my loved ones, stared down the barrel of my own mortality, and devised a plan. My cancer was rare, and the surgery I needed to save my life was no joke despite the fact that it is commonly known as a Whipple, a term that sounds more like a dance move than an eight-hour organ-removing and potentially life-threatening procedure.

My initial inclination was to have the surgery in Santa Barbara in the more-than-capable care of Cottage doctors. However, after a client of my wife’s helped open doors for us at Stanford Hospital, giving us access to the world’s undisputed expert on my disease, the choice was a no-brainer. I was headed north. My insurance company balked at the decision, but, thanks to the generosity and support of my family and friends, I was able to move forward with courage and deal with the details later. After all, you only get one shot at this life, and money — or lack thereof — has no business entering the equation.

I went under the knife on Monday, July 29, and I haven’t looked back. That feeling of otherworldly and uplifting gratitude that I felt that day in the Pacific has been my guiding light, undulating in and out of my being with an ever-increasing power and frequency. I have come to learn that it is fed by love and community and compassion, and the more I open to it and the more I look for it, the more it grows. I know this sounds like some seriously hippie-dippie stuff, but I promise you I am no crystal gazer. I simply, for the first time in my 35 years on this planet, not only know what truly matters but also am working to live a life that actually reflects it. It isn’t easy, and I don’t always succeed, but I try.

Ocean’s Affirmation

A few months ago, just as summer turned to fall — and well before I had my surgeon’s blessing to do so — I returned to the art of wave riding. It was mid-morning on a Monday, and I knew Rincon had a small perfect peeler bending into her cove. Before better judgment could sway me back to the couch, I was loading my truck and soon enough heading south on the 101, the whole world playing a symphony.

The first couple of rides were on my knees, quick little runners on the inside. The smile on my face was so big and stupid it hurt. After a good solid cry out the back reflecting on mortality, the pure wonders of this life, and how damn good the ocean feels, a solid waist-high wave seemed to pop up out of nowhere. Tears still on my face, my stomach still tight with the awkwardness of being a grown man crying in the lineup, instincts took over. I stroked into it and popped to my feet with no regard for the hundreds of stitches actively reattaching my insides and holding my stomach together. A brief fade to my left as I let the wall build in front of me before cranking back to the power source. Instantly I was locked in the sublime weightlessness of trim, and cancer was nowhere to be found. I let my right hand relax into the delicately breaking lip, pulled my feet in close together, and stood up as straight as I had since feeling the scalpel. There are no words to describe the sensation of that ride and what it meant to me. But I will say this: I have no doubt that there is an all-encompassing and transcendent power in this universe, and for me, it lives in the sea.

Back in the parking lot, blissed out and warming my skinny pale body in the sun before heading home, a guy, probably 20 years my senior with a face familiar to me from my past 15 years bobbing around the Rincon lineup, struck up a conversation. No doubt curious about the massive and still-healing chevron-shaped incision on my torso, he asked if I had actually “been surfing with that thing.”

Quickly we were connecting, and I gave him a CliffsNotes version of my recent history. I ended the blow-by-blow with an awkward, “So yeah, pretty much I should be dead, but, for some reason, I’m not. I’m here, and figured I’d try and have a little paddle.” At this, the man got serious, his brown eyes flashing with intensity as he reached out and grabbed me by my left shoulder. “Listen,” he said, “you’re not supposed to be dead, man. You need to stop that now. You are supposed to be alive.”