Review: Chris Baker Pacific

One Rembrandt Inspires Many Forms at Jane Deering Gallery

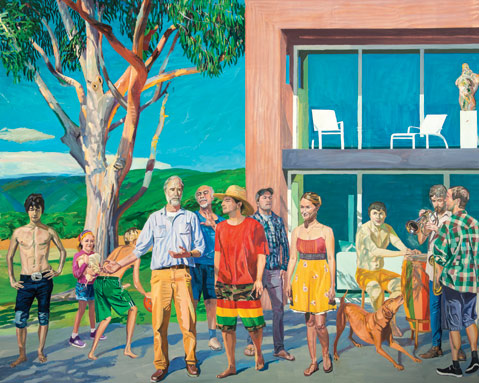

Twelve figures present themselves to the viewer in Chris Baker’s large (106″x 132″) new painting “Pacific” — 13 if you count the chicken. They’re mostly recognizable California types, and with the brilliant sunshine, modern architecture, and laid-back style of their setting, they could hardly be anywhere else. At the center of this majestic, brilliant-hued composition, a guy with a white beard almost holds the attention of a dude in baggy shorts, a red shirt, and a sombrero. To the left, children frolic, and to the right, a trio plays music, defining the image’s limits. Other characters occupy the middle, too, like the blonde in the yellow sundress, or the plaid-shirt man with the ball cap. White beard even has a sort of echo in the form of another white bearded man who stands behind him, gesticulating. Generous with color and light, the picture combines an old-world sense of grace and complexity in its composition with a fresh palette that is worthy of David Hockney at his best.

What’s not immediately apparent, and what makes Baker’s work so interesting and special, is that the inspiration for Pacific, which occupies one entire wall of the gallery, comes not from the likes of Hockney’s iconic “Beverly Hills Housewife” of 1966 but rather from Rembrandt’s much, much more iconic “The Night Watch” of 1642. Hanging on the wall opposite “Pacific” is another of Baker’s large new paintings, the 48″ x 72″ “The Night Watch Abstracted” (2014). Elsewhere on the walls and in the gallery’s flat files, myriad examples, each executed in a different idiom, all point to the same conclusion — Baker is obsessed by “The Night Watch.”

If you’re a painter and you are going to become obsessed with a single great painting, “The Night Watch” is the way to go. Packed with endless information not only about the merry band of sitters, who weren’t watching anything when they commissioned the picture from Rembrandt, but also about the possibilities of painting, its visual interest feels unlimited. In his abstracted version, Baker remains remarkably faithful to the arrangement of the figures in the original but lets loose within that with a tour de force of painterly distortions. Dragging a scraper across many of the figures with a light touch and a sure hand, Baker introduces the kind of horizontal smears one associates with a sticky printing roller — or the abstractions of Gerhard Richter. Baker employs other postmodern painting gestures here, as well, and a side-by-side comparison of his painting with Rembrandt’s original in digital reproduction reveals that such techniques as the incorporation of hard, stencil-edged fragments of negative space are in fact nothing new, as Rembrandt was using them in the 17th century.

In a brief artist’s statement accompanying the show, Baker suggests that his project is best understood as a search for order through observation of and meditation on Rembrandt’s sublime sense of composition. While ordinary artists are often reluctant to acknowledge their influences out of an anxiety that they may be second best, for Baker, the influence of Rembrandt would appear to induce a kind of ecstasy. With Pacific, he emerges from the long shadow of “The Night Watch” into the bright light of his own imagination.