The Egg Man Cometh

Humane Society Exec Talks Proposition 2, Chickens, Eggs, and Why Caged Birds Don’t Sing

Don’t make dumb jokes about whether the chicken or egg came first with Wayne Pacelle, the head and face of the Humane Society of the United States. Pacelle, it turns out, eats neither, being a vegan now for 30 years. But he stressed that that’s his own personal position, not that of his organization’s. Within the spectrum of animal-rights groups, the Humane Society is notably not doctrinaire about the eating habits of its members. Instead, it’s much more focused on the living — and dying — conditions of the animals raised under factory farm conditions throughout the United States.

Earlier this week, Pacelle (pronounced “pa-sell-ee”) got out of his L Street digs in Washington D.C. to take a statewide victory lap over the implementation of Proposition 2 — which expands the amount of space required for egg-laying hens — that California voters passed overwhelmingly in 2008. Prop. 2 is one of many new laws and initiatives that went into effect January 1, giving Pacelle a good excuse to stop in Santa Barbara to visit with supporters at the home of Paula Kislak, an area veterinarian and a member of the Humane Society’s national board of directors.

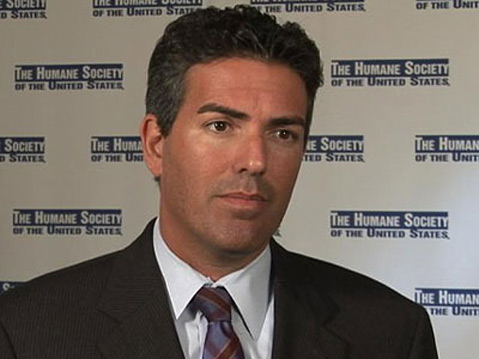

In person, Pacelle is smooth, polished, and at ease. He’s got well-coiffed black hair with a smattering of gray around the temples and feet that are distractingly large. He’s also got a ridiculous amount of detailed statistical info at his fingertips. During an interview at the Montecito Starbucks, Pacelle noted there’s about one egg-laying hen in the United States for each of the nation’s 300 million residents. Each of those hens produces about 260 eggs a year, which coincidentally is about the same quantity the average American consumes in a year.

The conditions under which these hens produce — jammed tightly into tiny cages and de-beaked so they don’t peck each other to death — gave rise to California’s Prop. 2 six years ago. The language of Prop. 2 stated that the large egg producers needed to give their hens enough space to stand up, spread out their wings, and turn around. During the campaign over Prop. 2, Pacelle said both sides agreed on only one thing — that if it passed, it would require cage-free laying conditions.

But Since Prop. 2 was passed by California voters in one of the highest turnout elections in recent history, Pacelle charged, the egg industry has changed its tune. Now, the producers are insisting the initiative only requires they provide hens 116 square inches, slightly less than one square foot. That figure was given by the California Department of Food and Agriculture, which recently determined that was the amount of space required to hedge against salmonella outbreaks. Although it’s nearly twice what the hens had before, Pacelle said, it’s not good enough. “Those new requirements have nothing to do with Prop. 2,” he stressed. “Instead of jerry-rigging their existing cages to hold somewhat fewer hens, they should actually do what they initially said the law would require them to do.”

Cage-free chicken-rearing is hardly revolutionary, Pacelle said. The poultry industry produces 9 billion meat chickens a year, he said, and they’re all raised cage free. “If they can raise 9 billion chickens cage free for meat, then certainly they can raise 300 million cage free for eggs,” he said. The broilers are not caged, he explained, because they would otherwise bruise, rendering them beyond the pale for most consumers. At the time of the campaign, Pacelle said, economic studies indicated that more expansive living conditions for egg-laying hens would increase the cost of production by “a penny an egg.” To the extent prices go up further, he charged, that’s because some retailers were taking unfair advantage.

Prop. 2 is only part of the new regulatory and economic reality affecting egg prices in California. In response to concerns that California producers would simply shift to out-of-state locations, the California legislature passed a bill (AB 1437) that required all eggs sold in California — no matter the state of origin — had to comply with state rules and regulations. This bill is having even more far-reaching effects than Prop. 2, Pacelle said, and is changing the way eggs are produced nationwide.

Egg producers in other states — as well as the states themselves — challenged these new initiatives in court, arguing they violated interstate commerce and the constitutional authority of California to establish poultry rules beyond its own borders. None of these arguments prevailed, however. Egg producers, waiting for the outcome of such litigation, were slow to build new hen barns. As a result, California is expected to experience a short-term egg shortage sufficient to generate a significant spike in prices.

Pacelle said he was making the rounds in California in part to celebrate Prop. 2, but also to make sure it was implemented correctly. Prop. 2, it turns out, makes it a criminal offense to raise hens in cramped quarters. In Santa Barbara County, enforcement is pretty much a nonissue. Rosemary Farms has all but shut down its Santa Maria operation, though it still maintains a residual operation with a few thousand hens roaming cage free and producing eggs for the high-end market. How the law will be applied in other counties has yet to be determined, but it will fall to the area district attorney, rather than the agriculture commissioner, to make the call.

Because it’s a criminal matter, Pacelle said, the Humane Society lacks the legal standing to file court actions of its own. Instead, he’s pushing big companies like McDonald’s and Starbucks to make a commitment to sell products made with cage free eggs. The moral argument, he said, often makes good marketing sense. “People are much more aware of issues involving animal suffering,” he said. “They’re much more tuned into deciding what foods to eat based on how that food is produced.”

When Pacelle isn’t out seeking voluntary compliance from Fortune 500 food producers, activists and volunteers with the Humane Society are providing raw video footage of animal abuse in hopes of inducing moral queasiness among average consumers. In recent weeks, for example, the Humane Society exposed a Minnesota slaughter operation in which “spent hens” were grabbed, hung upside down, and dunked into scalding water while still alive. A typical chicken, Pacelle said, lives 10 years. But the hens used for egg-laying, he said, are killed after 18 months. “They’re used up,” he explained, describing such hens as featherless creatures with negligible muscle mass. “They’re used for things like chicken pot pies.”

Pacelle said the Humane Society was initially gun shy about taking on the agricultural industry in California, a potent political force with vast resources. “We were skeptical we would fly into the teeth of the ag industry and prevail,” he said. Both sides, he recalled, raised about $10 million each. “We both brought knives to the fight,” he said. In the end, it wasn’t close. Statewide, Prop. 2 won with 63.5 percent of the vote. In Santa Barbara County — long a hot bed for well-heeled animal-rights advocates — it was 68 percent. But even in Kern County, Prop. 2 won, though with 53 percent of the vote. “We didn’t just wage an air campaign,” Pacelle said. “We weren’t just about TV commercials. We had ground campaigns with volunteers and organizers in all 58 counties.”

In the six years since Prop. 2 won passage, Pacelle said, the momentum against animal cruelty has accelerated. Yes, there have been some notable setbacks, like the recent court ruling overturning the ban on foie gras production in California. (Foie gras is made from the livers of geese that are force fed.) But there have been unexpected victories, as well. Just recently, Pope Francis declared that animals do, in fact, have souls, something decidedly counter to what most Catholics were taught growing up. “Animals have their own lives. They feels things, and they suffer,” Pacelle said. “We’re not saying, ‘Don’t eat animals.’ We’re saying, ‘If we’re creative and compassionate, they don’t have to suffer.’”