Focus on Five

A Closer Look at a Few Key People Who Tell West of the West's Story

Here’s a closer look at a few key people who tell West of the West’s story, from a Chumash descendent to a celebrity conservationist.

Lone Woman Expert

Even after six years of researching the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island, Susan Morris is still making discoveries. “It’s just so fascinating,” she said. Morris has corrected key details in the bloody chain of events that led to the Lone Woman’s nearly two decades of isolation, and she recently pinpointed where the marooned Nicoleño died of dysentery seven weeks after her “rescue” in 1853 — in an adobe house on the corner of Quinientos and Quarantina streets. Soon, Morris will publish a new report that sheds even more light on her time on the mainland.

Like most 4th graders, Morris learned of the Lone Woman by reading Scott O’Dell’s Island of the Blue Dolphins, which took some artistic license but largely stayed true to history. She was intrigued. So when Morris — a Ventura resident and independent researcher who’s studied the islands on and off since 1987 — got an opportunity from the National Park Service to develop an educational website about her, she jumped at the chance. The site will go live later this year and will link to a trove of digitized historic documents. “It’s not just the story about one person left alone on an island. It’s a history of the human race,” Morris said. “It’s what happens when explorers and entrepreneurs enter the territories of native peoples, and how they change and survive.”

Island Rancher

Tim Vail was the last of his kind — a fourth-generation island rancher far removed from urban trappings and the government regulations that eventually put his family out of business. The Vails began running cattle when Tim’s great-grandfather Walter bought Santa Rosa Island at the turn of the century. For more than 100 years, they herded their stock down a pier and onto a boat to get it to the mainland, helped by Sonoran ranch hands who lived with their families on the property that came to symbolize “a way of life that doesn’t exist anymore,” said Vail.

Though Vail has fond memories of his unique upbringing, early-morning roundups, and a beloved homestead that’s now protected by the Park Service as a historical site, he has a hard time returning to the empty ranch. “That island is gone for me,” he said. “The families are gone, the work is gone — for me it’s a very lonely place to visit.” Every so often, Vail — now a semiretired large-animal vet living in La Quinta — will check on the last few horses that remained behind, “old pensioners who earned their keep.” Vail said he’s glad to see his family’s ranch memorialized in West of the West, as it’s a piece of modern human history that often gets overlooked.

Kid Crusoe

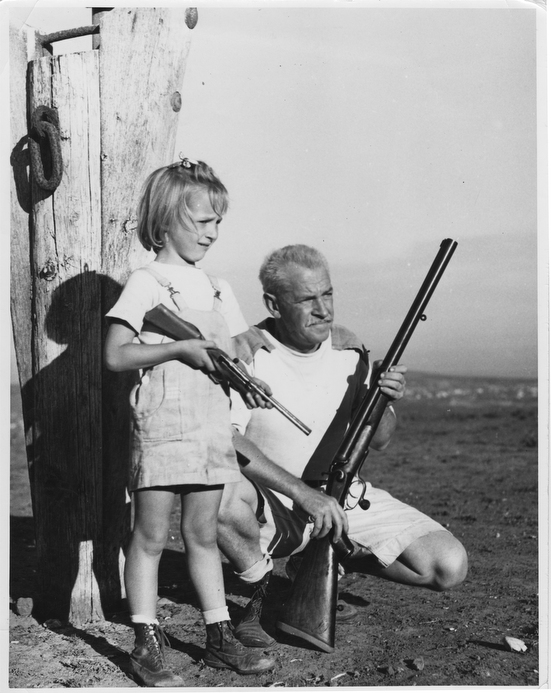

Betsy Lester will never forget her first arrowhead. “It was like finding a pot of gold,” she said. Strong winds exposed the Chumash relic on the east end of San Miguel Island, where Lester lived as a little girl in the 1930s with her parents and sister in a house made from shipwreck lumber and lit by kerosene lamps. She spent her days (when she wasn’t being home-schooled) exploring the remote terrain, discovering “little creatures like slender salamanders,” paying attention to “the noises different plants made in the breeze,” and learning cloud formations overhead.

After the death of Herbert Lester, who famously referred to himself as the king of the 10,000-acre island where he ran his sheep ranch, the rest of the family moved away in 1942 when Betsy was 8 years old. “I really cherish that opportunity to live there as a child,” she said. “It taught me you can do a lot with very little.” Lester studied zoology at UCLA and then taught science at a Beverly Hills middle school. She took her own kids camping as often as they could. Now 82 years old, Lester lives in a quiet Santa Monica canyon with lots of trees around. She hopes the film will encourage people to visit the islands “the way they are now,” full of history but empty of modern-life distraction.

Chumash Voice

When Santa Barbara Mission priests asked Julie Tumamait’s great-grandfather if he wanted to change his last name to Marquez — a more “proper” title, they said — he declined. That decision would preserve his family’s identity through the years; the Tumamaits are now the only lineage of area Chumash to have maintained their last name, said Julie. The rest have been lost to time and history. To ensure her people’s legacy is not totally forgotten, Tumamait has dedicated the last 30 years of her life to educating school kids and others about the communities that thrived on the Channel Islands independent of their mainland brethren and long before the Spanish arrived.

“Our culture doesn’t give the impression that there are native peoples still here,” said Tumamait, an Ojai resident, whose grandfather’s family came from Santa Cruz Island and whose grandmother’s family hailed from Santa Rosa Island. “There’s a vibration here that people don’t know about.” Tumamait encouraged residents and visitors alike to explore the history of native peoples, but to do it gently. “Don’t take things,” she said. “Take a picture.” We could all learn from her ancestors, she added, who lived in their environment instead of just using it. “Be soft with the world,” she asked.

Rock Star Enviro

The unlikely pairing of a rock legend and a genteel but ornery doctor saved Santa Cruz Island from oil development and a Disney theme park. Eagles guitarist Joe Walsh and Stanford-trained pathologist Dr. Carey Stanton, who inherited the island from his businessman father in 1957, discovered they had the “same wry humor and the same outlook on life” during one of Walsh’s first visits to Stanton’s cattle ranch. “He liked me, and I liked him,” said Walsh. “And we were of the same school of thought: Keep the island like it is.” When Stanton died, Walsh gave him his word he’d oversee Santa Cruz’s continued preservation. Thirty years later, Walsh is still the island’s big-name but behind-the-scenes steward, working with the Nature Conservancy and the Park Service to maintain its wildness.

Every so often, Walsh sneaks away from his life of recording and touring to “Walden wood it” on the island. “It’s very healing when I get L.A.-ed out,” he said. And every year on May 3, he visits its chapel for the Feast of the Holy Cross, a tradition that began when Stanton invited Monsignor Francis J. Weber to say mass, which he did for decades to come. Admittedly, Walsh is conflicted about alerting others to the beauty and serenity of the place: “It’s a jewel because people don’t know about it.” And he’s looking for the next person to carry the mantle of protection. “I just have the gut feeling that I was supposed to do this,” he said. “It’s a passion. I just hope I’ve made a difference.”